|

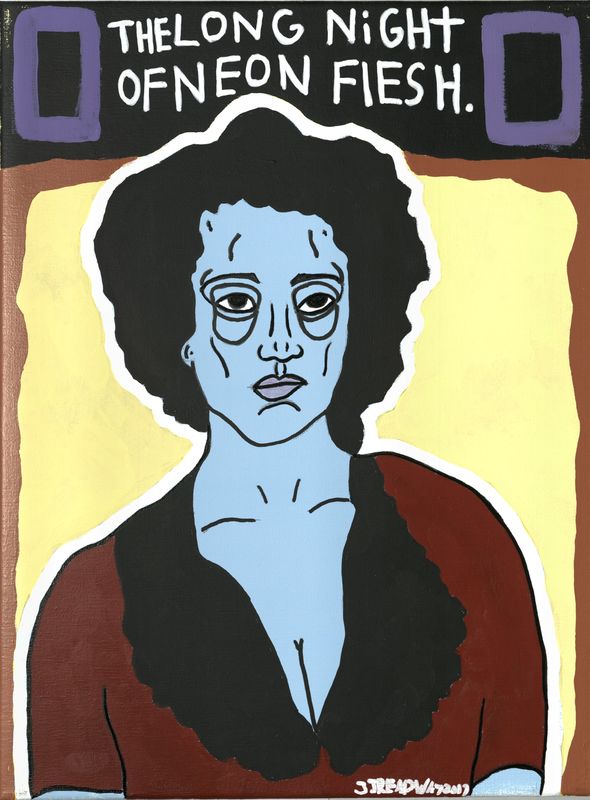

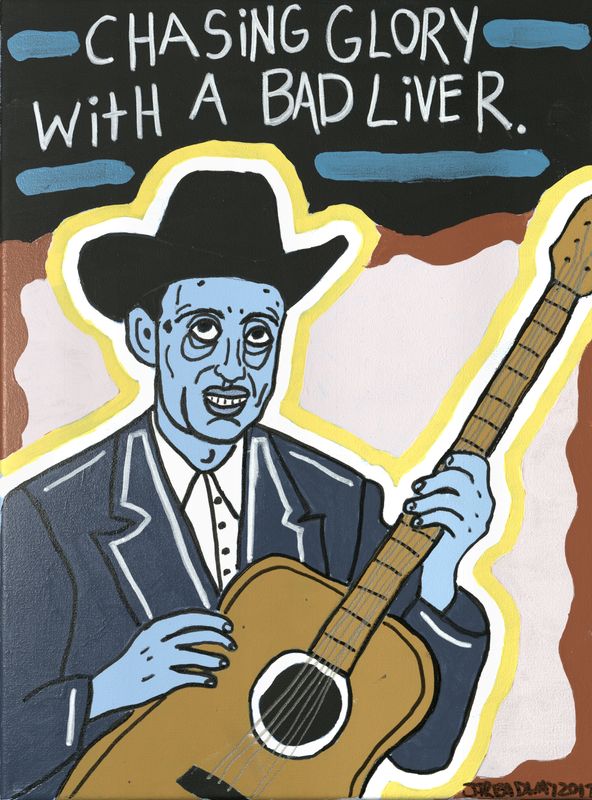

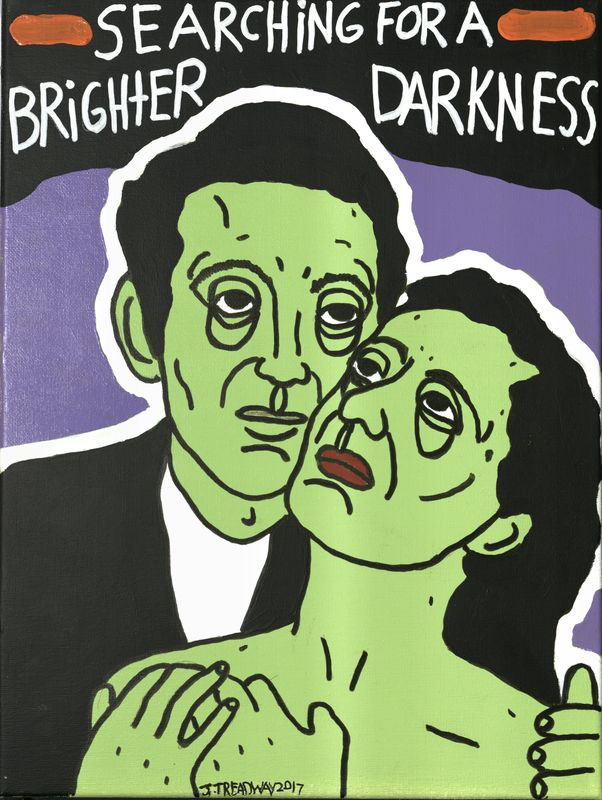

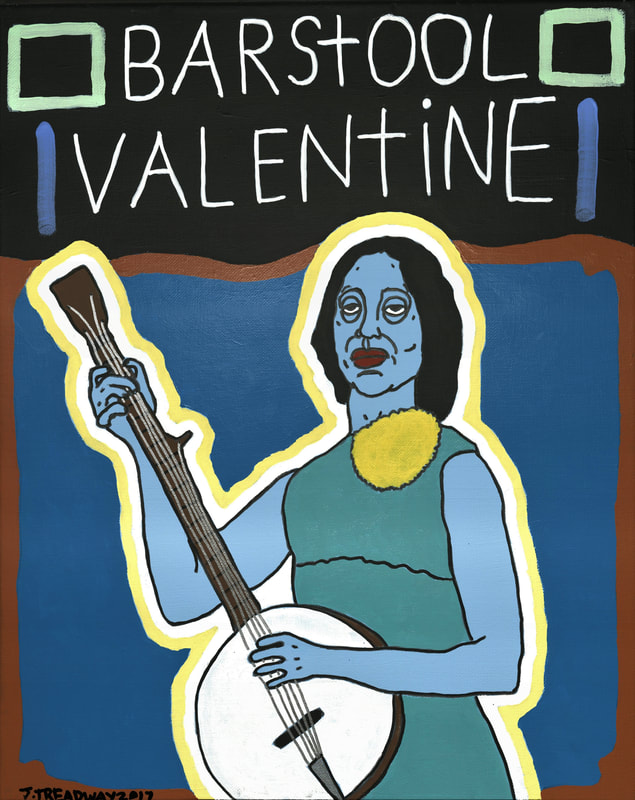

Like a Deleuzian rhizome, On The Wane perfects and fractures darkgaze sonic booms, as if the band's own bodies were tethered to the sounds themselves, a rhythmic pulse of city pounding dissonance and magical cohesion, all cohabiting in the same singular space of post-punk, call-it-what-you-will, it simply works. On Sultry Song there is a feel of the barely controlled chaos of The Birthday Party and Lydia Lunch's Queen of Siam, yet all distinctly brewed in newly woven and then shredded high octane musical muscle. Truth Isn't Bright, a softer side of the band, is a shimmering Cocteau Twins-esque shoegaze chant, with Sonic Youth/Bad Seeds abandoned factory guitar moans like a gothic guttural Elvis. Part post apocalyptic, and at times even oddly psycho-billy, On The Wane is an experience to be had, one of sonic transformation. They are less interested in repeating familiar forms than in constantly re-calibrating chaos into beauty, evolution and experimentation as both glue and unbinding agent. "The human race is going down" undoubtedly, and to a soundtrack for the end times. On The Wane is the best musical side car driver around. The Doom Generation for the 21st century, a Gregg Araki industrial convulsion, spooky, spectacular, and always unexpected. "I'll set your house on fire," this music is not fucking around, all the more reason to love it. Schism, by On The Wane is available now via Bandcamp Facebook Twitter www.onthewane.com/ 1/22/2018 Poetry by Isaac Stackhouse WheelerCarthage Must be Destroyed Certain temples are ceremoniously pulled down, which we in the West hesitate to class as monuments, and are cyclically rebuilt on the same ground, explained the radio while I drove to the clinic to have a malformed toenail removed. The doctor assured me that the body was good at resuming its former shape, and the new nail would grow smooth and straight without a trellis— but it is not so good as to deconsecrate a soldier’s leg, long since removed, of which the pain remains, a wet shell hole sound that stalks his civilian stride, the inarticulate slosh in a left boot no longer worn. So even on this salted beach, drunk until the weightless shine of the surf is abstracted off the ocean, I convolute my limbs that retain the ache of when they were involved with yours. They bend to mimic the elbows of the kelp that throngs up through the streets of some long-conquered Venice. All that heft of alleys and alcoves is so much sand, which, with the merest shrug, should tumble chastely off the skin, but your name remains a Carthage enclosed in my hide.  Bio: Isaac Stackhouse Wheeler is a poet and translator from New Hampshire. His latest translation project, Mesopotamia, a collection of short stories and poems by great living Ukrainian author Serhiy Zhadan, is forthcoming from Yale University Press. 1/20/2018 Poetry by Nicole MelchiondaTo My Mentor I remember the first day we met: you floated in, camouflage pants, combat boots, tattoos, those explosive ashy curls, and you asked us to call out our least favorite word as you wrote them on the whiteboard. Mine was discombobulated. Perfectly metrical, you said. You were the first teacher I ever heard drop the unspeakable f-bomb. My sapling ears unfurled as each dendrite zipped to the staccato -/ of every subject you traversed. You lectured us for ten minutes on why “moist” makes everyone uncomfortable-- something to do with the movement of tongue against roof and compression of lips, some mouth science you knew well. I’d been writing poetry since I was twelve, thinking I was hot shit, but quickly saw underneath your scalpel that experienced bones don’t always carry talent in the marrow. As I evolved, I wasn’t aware that I was coral, housing fleeting mythos, collecting increasingly deeper abrasions as they squeezed through me. You were raised Catholic but embraced your daughter’s girlfriend. Funny, I thought, that so many Catholics had gay children. I was baptized Protestant, but born an atheist. You spoke nonchalantly about going to therapy. I wondered if you needed help because you were losing your religion. Your forearm is bilingual. I’d squinted at your inky branding many times: pessoa. “Person,” you explained years later. “The only label I want to have when words are all we have left.” You told me your secret, bared poignantly but with ease in the constricting, safe womb of your office where we bonded after I confided in you that my story of abuse refused to conform to any poem. You told me that sometimes the best way to exorcise those feelings is to assign them to a different story. I realized that your hair must be so big because your skull struggled to contain all of your force. Then I learned you had a son from that poetry collection you wrote. I understood this was a wound too fatal to speak aloud. I’d knock the breeze right back into you still if I could, one whipstitch in time. Winded, I recalled years ago when I mentally constructed my note, which was flushed away slowly by the heart that refused to stop beating, and it feels so unfair that you never got his, that I am here and he is not, that so much shrapnel can be carried in one woman, in one smiling woman. Pseudomorphism I worried you’d come into me as galaxies of untethered cells and that each of my lungs would absorb your entire biosphere. Yesterday I touched the Barringer meteorite and felt uneasy about mother/land, that I could unearth my vessels and lasso past our asterisms to strike the millionth lightyear from which it came, retrace the cosmic migration we once made. These neurotransmitters were regifted from my blood sibling through burst sulcus. We are both broken, but mindful of our endeavors dated beyond forever. When I held that sliver of myself in my palm, all I could think about is how we procreate until our numbness fades, and I will simply become a body of bodies, no longer as mystical as our origins. Thyroid Storm Virginal blood smudged on your doorframe was the contract we signed unknowing the borders between our bodies would dissolve and like a primitive Hephaestus, we would pound ourselves together, molten metal and all, until we screamed as one. Memories were once clearer than surfacing veins but now I can’t recall my life before our reincarnation. Your blood swaddles poison and I can’t drain what’s rotting deep below. For years I’ve panicked until I met death and felt the visionless void wringing my lungs: I can’t bear the thought of carrying two minds in one oversized body. I dream of news reports where paramedics arrive ten minutes late, and consoling professors gift me the sketches of your tattoos, and wailing on the kitchen floor at the sight of our utensils spooning with only one hand to pull them apart. I awake and like a newborn monkey I cling to your back. With the horrified helplessness of onlookers who hear me curse my unused fertility still fresh in my dream-widowed cortex, I beg with a mouth full of cotton. The tears on your shirt too impermanent and unbinding, your heart chugs on with indifference and your plate still waits for the morning oatmeal.  Bio: Nicole Melchionda is a graduate of Stetson University where she majored in English with a minor in creative writing. There she completed an independent study on gothic poetry with award-winning poet Terri Witek and earned membership to Phi Beta Kappa. The interests that infiltrate her work include biology, human anatomy, cosmology, psychology, and interpersonal relationships. She has worked as an English teacher in China and now resides in Poland. 1/19/2018 Poetry by Hamish Todd SomeDriftwood CC

DISREGARD I long For the time When I wrote About human things About love and betrayal Exploring color and feelings And emotions But I can only Think of the plastic That has been found In every part of the ocean At every depth The micro threads from Modern clothing And remnants Of plastic bags And toys and pens and sippy cups Threatening even The plankton Who feed everybody else Whales are starving to death Blues and Greys and Orca It’s only a matter of time Before we’re all choking On our own recklessness And total disregard for anything else Save our own wretched species Strange Salvation Is that proof, what kind of proof? I am the proof I am the evidence This was all a long, long time ago I was cast out By thick skulled men In blood red robes I was bound and beaten And made to catch their vile urine In my mouth Lest they beat me to death And ravage my corpse I have seen Jesus I have! He came to me in my sleep And He begged me to give up drinking He stroked my hair It’s alright, he said. It’s alright The wind blew and his olive skin smelled of rosemary and the sea And I tried to speak but he bade me to shhhhhh, “Be still.’ In the morning I woke refreshed School girl blue in a Catholic dress Knowing I’d had God in my mouth I’d had God in my mouth I’d had God in my mouth, like bread Bio: Hamish Todd lives and works in Port Orchard, Washington 1/19/2018 Poetry by Ashley Cooke Wendelin Jacober CC

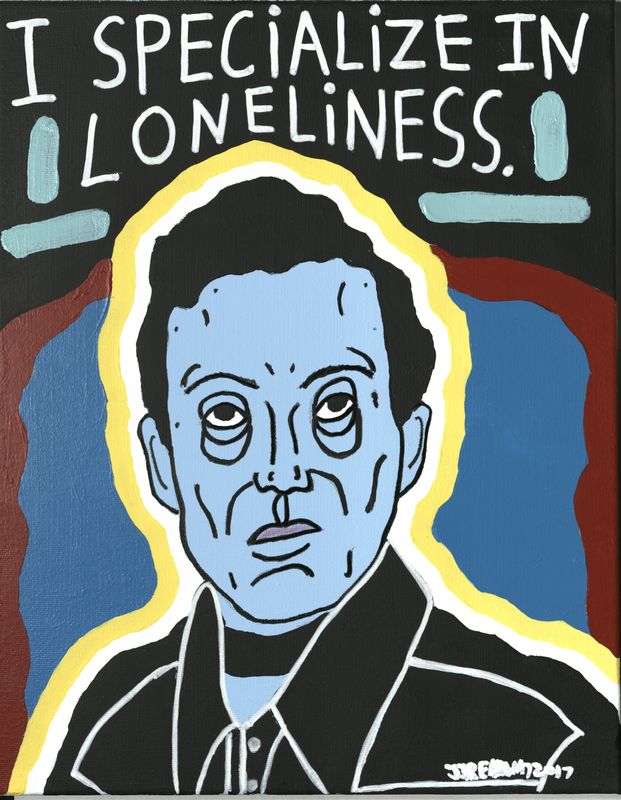

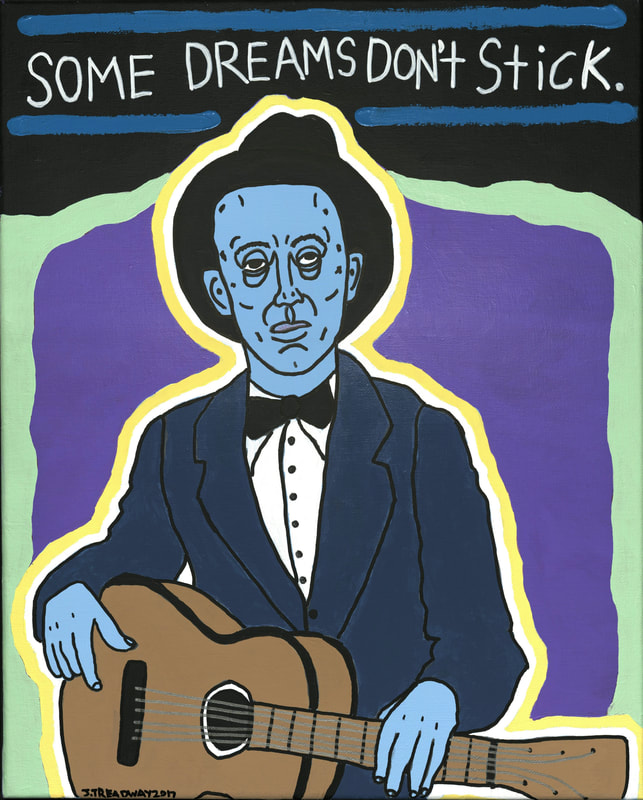

Slow Dancing Last night we slow danced in a room filled with skeletons we held each other tight nearly floating across the room all that mattered was our touch we never let go it never crossed our skulls. Scars Their scarred knuckles scraping across the same bricks they slammed their fists into long ago their feet trace the railroad tracks beneath them that lead them back to the house that had been vacant for years that stinging sensation came back from the scars that were risen here looking around at the past brought a piercing ache to their heads they remembered why everything hurt the way it did when they were young. Bio: Ashley Cooke is a creative writing major attending Long Beach City College. She is from Long Beach, CA. She is currently working on her first poetry collection entitled “Like Pulling Teeth”. She works at a hospital and at a music venue. She has been writing poetry for 10 years. What becomes of us when our lives suddenly turn uncertain, stricken with debilitating, dire illness? How does the spirit learn to breathe, day to day? Friends, family, creativity, faith, they move us even when we cannot. Through them we survive and feel our lives not in vain. Taking up the warm hand of a loved one, writing a poem, the small and the ordinary, the large and over looming, we learn even while we die, and while we live, what else can we do but hold on for dear life? To make the time we have matter, as painful as each minute can sometimes be. As Chrissie Morris Brady faces the grim realities of her declining health, she does so with courage, authenticity and hope for others. "When light seems to be missing, I must ask God to show me where it is, what am I blocking it with?" asks Brady. "Light puts out darkness, and even in the night we have the moon and the stars. I am a pretty broken person so there are cracks. That's how the light gets in." AHC: Could you tell us about your experiences living with the illness that you are facing and about the illness itself? How you have mustered courage and acceptance through such a harrowing ordeal? Where have you found your guiding light or inner thread all these years? Chrissie: When the illness first appeared, I was very athletic. At first, I could not control my left hand so I began writing with my right hand. But it became noticeable and I would be asked if there was something I wanted or needed to talk about. I never knew what to say. Subconsciously, I wanted to express that I was bewildered by my left hand. It did not seem to be fully a part of me. I guess I tried to ignore it, bury it, as it was not every day that the symptoms were evident. Being ambidextrous, I would use my left hand on the days I had no symptoms. I guess my parents took me to our doctor fairly quickly. They were told I was attention seeking. Later, I was referred to a psychiatrist who asked me if I thought I'd lost my penis and similar questions. I recall giving one-word answers that I thought would please her. I thought she was insane. My Dad would have been my strength at that time, and the continued friendships. Also reading, I read so many books, I just found such safety in words. Little did we know I had contracted a lethal disease, that would almost take my life. I eventually became twisted up by excruciating muscle spams, having lost significant weight, with my left arm and leg flying around uncontrollably . AHC: You wrote recently that you have no fear of death itself. That the fear that comes to you stems more from the flight or fight response. How did you reach this place of acceptance and not fearing death itself, it seems a terribly high internal mountain to have climbed in order to not fear the end? Chrissie: I don't think of myself as having climbed an internal mountain! I see myself now as Chrissie, the woman, a social campaigner and, maybe a poet. When I woke after my third brain surgery - I had four, conscious,- but during this one I had 'snapped', screaming with fear and isolation, and having had enough. More than enough. I remember lying in what I thought was some sort of anteroom to God's judgment, and I thought, 'I don't know God'. I initially set aside my thoughts that I didn't know God. On finally doing rehab and speech therapy there was so much rejection in society for me, and no more athletics, that I couldn't equate knowing God with such an arbitrary occurrence in my life. I had no difficulty believing in God - the beauty of nature declared him to me all the time. It was a few years later, that I started to 'look for him', and in all honesty, I fell in love with God. Having gone through such horrendous surgeries, having been in locked in syndrome, having faced so much rejection and discrimination, death seems like going home to a safe place. AHC: You also go on to write about the small kindnesses and every day graces that you fill your life, the things and people you are grateful for, has this gratitude, in the face of pretty scary life-effects been a work in progress for you through out the years, taking stock, through the pain, of what and who makes this journey a little more bearable? What or who are you most grateful for today? Chrissie: I started to work for an international charity, and, seeing so much unnecessary poverty and disease in less developed countries, I decided to be a thank you letter to other people. Not just those I served through my work, but my colleagues. I smiled a lot by nature, and it didn't feel hard to do a little extra, an act of kindness, fulfilling a need if I could, instead of 'hoping that works out'. I spent three years in California, working with people in recovery from drugs or alcohol. I was amazed by their response to love, rather than 'these are the rules'. Of course, there is always a time to point out the rules, it's just that love and compassion seem to go so much further. I did my best to follow the teaching of Jesus, and I find the simplicity of his message both challenging and rewarding. It's been the last three years, since I was told remission was over and that exposure to damp had taken away my lung capacity that I had to find more meaning in my life. I had written poetry in my teens had taken it up again when my daughter went to school full time. Poetry was a way to express my creativity, my political frustrations, my longing for an alternate life, and memories. Now I felt something of what had befallen me should be shared with people I might not know in the hope that something I've gone through, experienced or overcome might resonate and bring a sense of connection, relief or hope to others. My daughter makes this journey more bearable. She is delightful, talented, and I adore her. My goddaughter also brings me joy, and so many of my friends who are now scattered around the globe, a friend who is a vicar who turns up to do any number of strange tasks. I'm grateful to friends I've lost to cancer for their bravery, and though I miss them so much they have given me so much. We tend to take so much for granted that it's easy to lose wonder. I look at the sky at night and feel awe. I look at flowers, leaves, trees, animals and see so much beauty and imagination. I don't know if I have heightened awareness because I've been so close to death, but I feel such appreciation. I'm no Pollyanna, I feel no compunction to see good in everything. There are heart-wrenching events all the time. I do my best to highlight these and be part of change for the good. I am so grateful to my Dad, John Morris, who taught me grace and a stoicism that is not 'stiff upper lip'. My mother complained about everything, made a drama out of nothing and I had no peace in her presence. I would sit with Dad for hours, reading, or watching a western, walking in Purbeck or the forest, birdwatching. He died peacefully in my arms last March. AHC: Has poetry been a coping or acceptance mechanism for you through this illness? Has creating and writing it out, felt empowering, like lifting a lid off a steaming pot, a release of hot air rushing into the open, allowing you to breath a little, even if only mentally, spiritually? Chrissie: Poetry has been neither of those things most of the time. It certainly is breath, though. Poetry is so many things - a photo of a moment, a story, an outburst of anger. But deep down I'm just a person like any other person. It's hard to know how much this disease has shaped me my personality. Poetry satisfies something within me for sure, the love of words, the expression of something elusive or a metaphor for the obvious. Certainly, it sustains me but so does my daughter. AHC: What are the life lessons you are learning at this season in your life? You deal with and toil under uncertainties shadow, but feel and reflect so much of the sun and of life. Many of us forget to do that and we aren't up against a thing as big as this, what advice do you offer others about appreciating and cultivating higher ground in our daily lives? What are the darker moments like, when that light is missing and you search, high and low, for reminders, remainders? Chrissie: The biggest life lesson is gratitude. I am grateful that I can see, hear, taste, feel, laugh etc. Friendships are so important and connecting in a more distant way with poets, publishers, and other like-minded people. Letting people prove themselves before I open up to them - I have felt misused so many times. Forgiveness, I know I need it so many times, so who am I to withhold it? My darker moments can be torment, when a symptom bothers me, or there's a leak in the bathroom and I must deal with it. When light seems to be missing, I must ask God to show me where it is, what am I blocking it with? Light puts out darkness, and even in the night we have the moon and the stars. I am a pretty broken person so there are cracks. That's how the light gets in. 1/17/2018 Poetry by William R. Soldan Mandee CC Winnipeg We were only a few months into this, us, this thing we have, when her uncle wrapped his hand around mine like a vise only doing what it was made for and said, Welcome to the family. I listened for the unspoken note beneath it, the one that had trailed every first love since the second grade, but then they pulled me into the fold and slapped my back. I waited. And now, these men talking of hockey and horses instead of dope and prison. Celluloid negatives of the ones that live in my strands, whom I’ve only ever known in faded snapshots and bygone summers, but who emerge at the worst of times. At the Opium we drink, and I speak with that lilt of drawn out vowels and slightly upturned phrases, all in good humor till I can’t stop myself. I gauge the reaction of the bartender, who’s been kicking us every couple on the house because the night is young and the house is dead. He’s a good sport. My old man’s from Wisconsin. Got family there. You all remind me of them, only less pissed off all the time, ya knooow? Out on the street, a man and woman, First Nations, share their curb with us and we croon together, he and I, and I think, Who am I to feel displaced? The woman keeps telling the woman I love she loves her style, and the woman I love gives the woman her skirt, and that’s part of why I love her. The woman cries, and they spin in circles. The man and I share drinks from a bottle of Kokanee beer. What we speak of is anyone’s guess and matters little. He chants at the moon, and I listen. In case this is the rest of our life. In case this is all there is. Street Kid’s Guide to Coming up Aces in Columbus, Ohio Key to making it’s this: First, stop caring. Standards of living—bring ‘em down. Especially in warmer months—May through September things really open up; winter gets tricky, but there’s always migrate west or south or, if you’re really desperate, borrow an address, some digits, get a job till things thaw out. Only if you’re desperate, understand. Next thing’s knowing Jimmy John’s offs their day-old bread for fifty cents, a little over three cents an inch, so jump on it. Ain’t tough to come up with a couple quarters, and bread’ll keep you going a long time. Then hit up the UDF Dumpsters on High, usually good for a sixer or two of expired brew. Bread, brew, a guy’s got practically everything he needs. Smokes—strangers can be good for one on the street, but posting up outside the Shell station or wherever is how you do it; most cats’ll oblige when you catch ‘em peeling the strip off a fresh pack. When all else fails, the snipes in the ashtray sand outside B-Dubs are some of the longest in town, if you don’t mind sucking on someone else’s filter—and for real if you’ve already hit the needle (come on, ain’t no one judging you here), then what’s a couple germs in the grand scheme? Oh, and there’s those Micky D’s coupons sold in books in summertime: ten sundaes, two bucks—nothing like a spoonful of cool cream on a hot day. That’s the gist. Just remember spare changing’s an art. Bring it. Spit some lines. Pick a tune. Shit, hit a lick with a grift if it’s in you. If you got the steady hands and can keep straight your bent truths. Finally, you’ll need a place to sleep after coming down from running hard (because that’s how we do out here), a few hours to reset or a whole day through. And in a town like this, for real there’s always somebody. So Fast, So Close I. Your mother tells you about emancipation, a way for you to be on your own, since it’s what you want. Think about how maybe it’s best for you both. Just sign on the line. Only once you do, you can’t turn back. Can’t return to wrist slaps and second chances. II. The Petra station doesn’t card and lets you run a tab. And why not? You’re steady and they know where you live, tell you so when you say, Toss it on what I owe you. They show you the shotgun, and you know the deal. Nothing subtle, just what it is. You come in to cash a check, settle up and start over. Had some work, a friend of a friend knew a guy. Enough to get square. Back at the house one of your roommates is in the driveway talking to some sketchy looking dude you’ve never seen. You’re about twenty ounces down then flat on your back in an upstairs room staring into a pistol’s cold pupil. Everyone’s on the floor. Don’t even know how many there are because you’re not about to move a muscle to count. Then it goes from bad to full-on ugly when they take the girls right there—nothing you can do but listen to the sounds of it. You know it’s over when someone says, You seen our faces, now you gotta die. They crack jokes and leave down the back stairs. You read about it in the paper, in the mall of all places, looking at words that are supposed to tell what happened while all around you people move in and out of stores, safe and flush and miles away. You console yourself with the dubious truth that if you’d have acted lives would have been lost. You’d be gone. One day you’ll write about it in fragments and failed metaphors. Trying to make it mean something. But for now you move on. You get by. It’s what you do. III. And this is where you see her first, twirling a mad mezcal dervish in the damp grass. Long skirt and bare arms. But it really begins when she lays her feet, crossed at the ankles, casual as slow honey in your lap. You can’t keep your hands off each other after that. Fuck in the water and in the trees, on table tops. Washing machines. Every cliché. Fuck because Love could take more than either of you’ve got to give. IV. Talking books and music and other tastes and tasting each other on the floor of your friend’s apartment as the early morning blue bleeds through an empty bum-jug of cheap Sangria. You make her coffee and share the last cigarette, which marks a great transition. Let’s not call it a thing, she says. No, you agree. Not a thing. But neither of you are stupid enough to believe it. V. You have a scare and tell yourself, I would have done right, would have stepped up. And then again to call your bluff. VI. Five days old and he lies in a blindfold under UV lights. Jaundice. Head coned from the vacuum. They give you a special blanket to wrap him in when he needs to nurse. But the light is what he needs and the blanket—it just doesn’t seem strong enough so you put him back under the bulb. They prick his heel to test his blood, bilirubin, and he cries, lies unclothed beneath the light. And he cries. All you want is to pick him up and let him see your face. But he needs the light. You need the light. And just like that it all comes back in blinding flashes, all those lows and close calls, and you fear for your child because he is your child. Then the questions spin from one another, from images of all that could go wrong in these first days and the days that follow and on and on until forever comes to a stalling halt. They weave this picture of a life so fiercely sought and fought for, but it knots you up because it’s not just yours anymore. It’s yours.  Bio: William R. Soldan grew up in and around the Rust Belt city of Youngstown, Ohio, where he lives with his wife and two children. A high school dropout and college graduate, he holds a BA in English Literature from Youngstown State University and an MFA from the Northeast Ohio Master of Fine Arts program. His work appears or is forthcoming in publications such as New World Writing, Gordon Square Review, Thuglit, (b)OINK, Anomaly Literary Journal, Ohio’s Best Emerging Poets Anthology, and many others. You can find him at williamrsoldan.com if you'd like to connect. 1/16/2018 Artwork by Jonathan TreadwayBio: Jonathan Treadway is a self taught Kentucky folk artist. He was born a preachers kid in 1976. Guided by the spirits he went on to fail at the family biz. Now, he spreads a new message from His church of paint where oblivion shouts, can I get a witness? He lives and paints in an attic apt. in a house built in the 1840s that both sides of the civil war walked in front of in Bowling Green, KY, 65 miles north of Nashville. He is also a poet and former Rock n roll singer. He paints omens, spirits, visions, dreams and secular saints of lost America. In his mind, the paintings are a call and response hymn with his phantoms and shadows. The paintings are of the dirty and fraid holy, the blessed and damned from times echo. 1/15/2018 The Ley by R. M. Francis SomeDriftwood CC The Ley It’s the Wren’s Nest - part housing estate, part nature reserve - it’s the Wrenner to us. Frogspawn slicks in silica sheets across Green Pool; Carrion crow calls; The foxes den - too close to the road - vixens crushed against tarmac; limestone cliffs weathered by prehistoric waves; the underground caves - the fenced off caverns - the canal lines that vein through; rabbits, badgers, weasels; and rusted cans and cigarette buts and flytipped sacks and discarded clothes and the stained knickers of a fallen wench; limes, acorn, hawthorn, bluebell and stinky wild garlic; bell pits, old mine shafts and geological tools; dog walkers amble through slippery tributaries of homemade paths; rope-swinging kids up a height in the oaks; the silence; the almost silence; the rhizomes that pierce through earth’s hymen and tangle, conjugate, apomixis, epitoky. None of this is metonym. This land is where we live. The Wrenner. Here is where they dug into the earth and pulled out a giant trilobite - the Dudley Bug, they call it - not a metonym. The streets orbit the woods, not as a symbol, literally. Terraces, clad in cobblestone and redbrick, meander, side stream, feed, branch, in swirls around the pull of the woods. The estate eddies the woods. Grandson lives with his brood three streets down from Nan who took the cousin’s house who now live up by our auntie, she’s been there for three generations and the kids’ll have it after too, and John and Wendy are two doors up from her sister and their babs are just through the alley next to our kid who used to live with her best friend at school and she’s only a stone’s throw from her grandson. Every bloodline webs our Wrenner like this. You say you don’t walk through here at night. You say to be careful. Avoid us. But we are here. Like the frogspawn sticking to the film of algae we are cells, sucking at light, stunned in our own kind of beauty. [...]The Wren’s Nest - part housing estate, part nature reserve - the Wrenner, we call it. Here’s where the Dudley Bug was torn from the earth. Where rodents, birds and sneaky mammals lerk. Where caverns and bell pits sit strong in limestone frames. Where trees nestle with grasses and nettles. Where green pool sits and sends out its rare stench. It seems still. It is still here. A litter of foxes learn to avoid the traffic. Hawthorns learn new ways to grow thorns. Prehistoric waves mark out our veins. This is not a metonym. It is where we live. The boarded up and barren houses are not symbols. They still orbit the woods. There are only a few of us left. A brooke remains from the pluera streets. But a brooke still has its stream. We await rains. We look still. We are here still. We are the frog spawn that slicks in silica sheets. Somehow breeding. You say you don’t walk through here at night. You say to be careful. Avoid us. But we are here. Fewer in number. Almost motionless. Almost quiet. We’re Wrenner ay we.  BIO: R. M. Francis is a writer from the Black Country, currently researching his PhD at the University of Wolverhampton. Author of two poetry chapbooks: Transitions (The Black Light Engine Room, 2015) and Orpheus, (Lapwing Publications, 2016). 1/15/2018 Animal Highways by Hamish Todd Clinton Steeds CC

What about a highway for animals? Great greenbelts, Northgate or Southcenter wide. Five, ten, twenty acres wide, with highways and biways above. A future park, running the entire length of the country. No cars allowed. A great swath of land and waterways, protected from traffic and noise and fences, and cigarette butts and soda cans and candy wrappers. Some folks I met from Sequim were telling me the wild elk population is in danger. Couple of years ago, my wife and I saw those elk, roving harmlessly, dangerously close to someone’s spiffy new back yard. I saw then, the farmland being carved up and parceled out, in ever smaller parcels, and I knew those elk were in for hard times. And sure, people need some place to go, but what about the elk, what about the animals, the bobcat and the deer? Will we mall in America? Will we lay cement over every blessed thing? Connect every sprawling suburb, to every other suburb, until the country is nothing more than a labyrinth of highways and parking lots and shopping centers, and fast-food drive throughs? Look at the photographs from the turn of the century, the Denny Regrade; after the Gold Rush, Stevens Pass, the early days of the railroad. Look at the amazing feats of engineering. We blasted holes in the sides of mountains; moved mountains to make waterfront; chopped trees down the size of a nuclear submarines. It is obvious, man can do just about anything he wants to. But, when we build, or start to rebuild for our children and our grandchildren. For that part of ourselves that doesn’t care about the paychecks and the mortgage payments as much as they care about the planet, this idea may appeal to you. Why not re-route some of our highways, undam some rivers? It will cost less than a country with no wild places; no place to get lost or build a rope swing over the water. It will cost less than losing our natural history. There are alternatives; progressive city planning (see Portland, Oregon); land trusts; reclamation; new zoning laws that benefit everyone, not just motorists. Our twin stadiums and P. Alllen’s Rock n Roll Museum are all very nice, but already we have some of the worst roads in the nation and don’t even get me started on parking. Wouldn’t it be nice to see highways for wildlife. And the next time you’re up by LaConner and Sedro Wooley to look at the tulips, wouldn’t it be nice to see a herd of wild elk, still free to walk, unencumbered, without tripping over some pink stretched plastic lawn chair. Bio: Hamish Todd lives and works in Port Orchard, Washington |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

April 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed