|

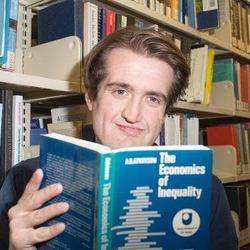

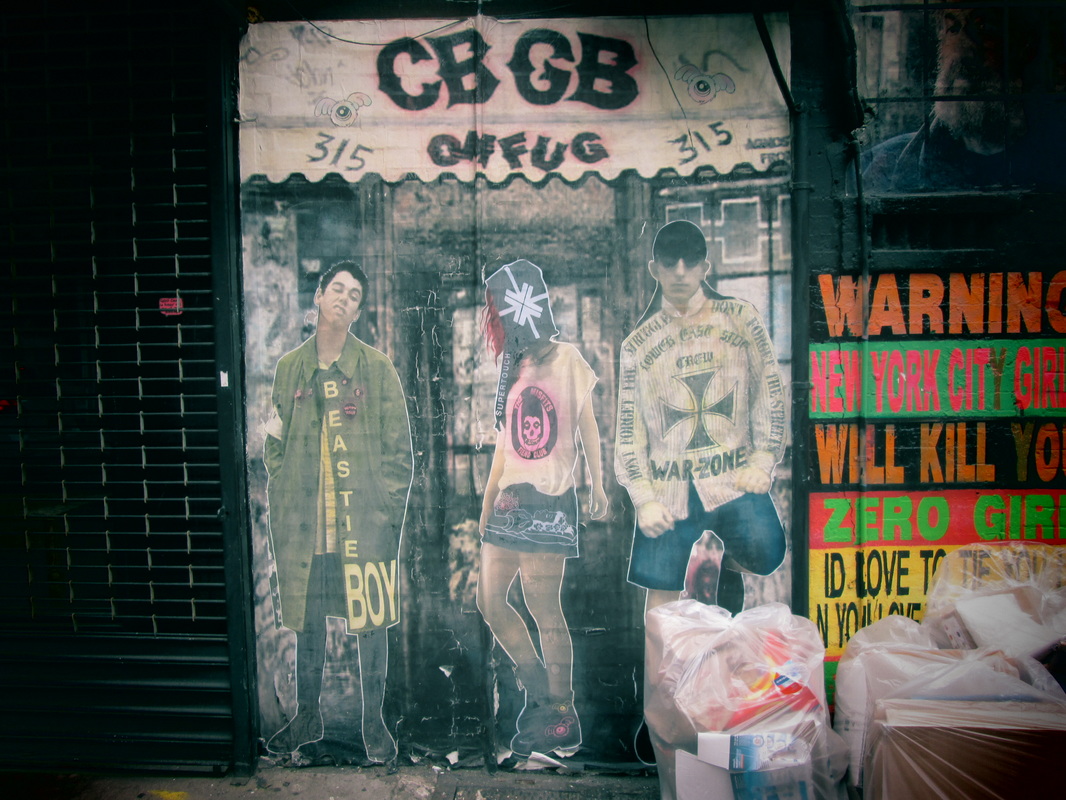

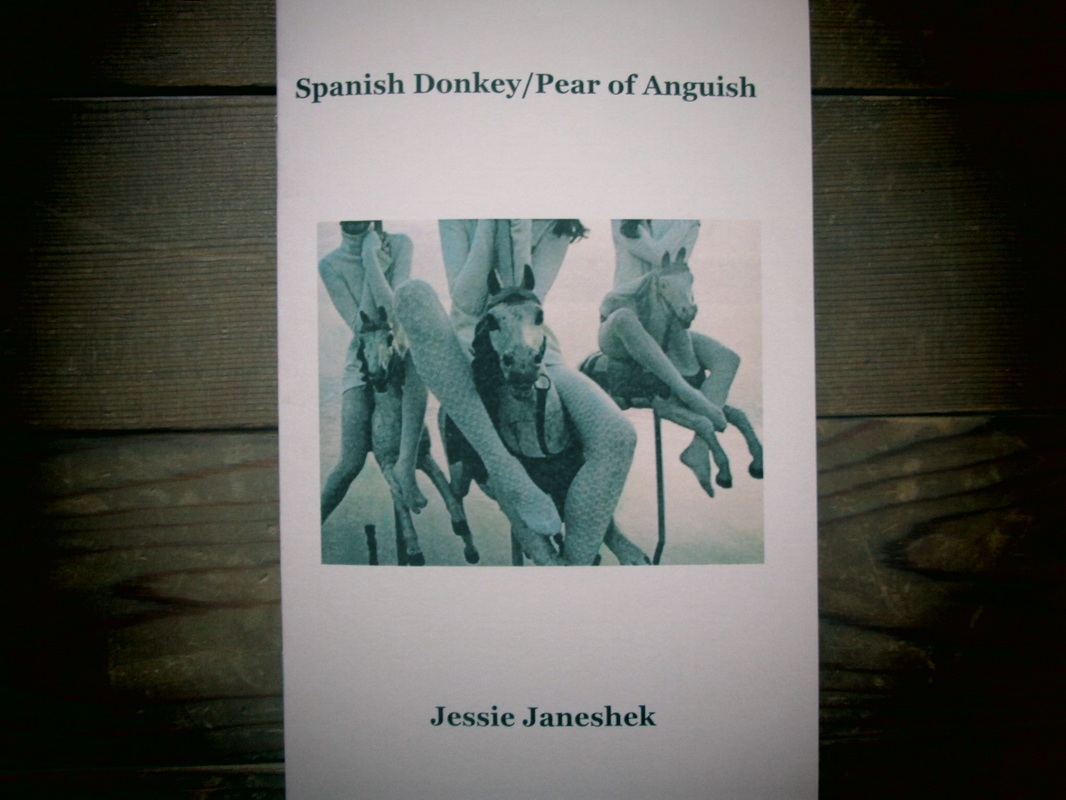

Fainting Distance: A Personal Reflection It always starts with something: that glance across party rooms, that foolishly brave approach at a bus stop, that awkward handshake after a mutual friend’s introduction, or, increasingly, one of those bubble number popups on a screen we’ve become familiar with. Those smooth bits of digital code wrapped in the finest design a poorly-paid intern could come up with hold out a kind of promise. When you’re in a new and unfamiliar place, without knowing especially who to talk to or what to do, the promise of that blinking digital light takes on even more significance; it says you’ve been noticed, it says you’re alright enough and, most of all, it says that someone you don’t have a prior obligation with is willing to take that most human of jumps to spend an evening of their life with you in hope of something greater still. There was a distressing similarity of myself to the cliché of the young-20s go-getter with respect to moving to London. Not to bore, but it was one of those ones with an internship, a foundation grant and 10 weeks sharing a Docklands Light Rail car with seemingly half the population of the world and a cramped AirBnB apartment with a group of New Labour professional types. I’d switched over the location on my long-unchecked OkCupid profile for the occasion, telling myself that I didn’t think much of it, but really holding out a weird kind of hope that everything might just work out this time. Surely, London had everyone, from every land of the dead empire, in its sprawl and, surely, one of them might take that jump with me. I suppose that now is as good a time as any to mention that, being asexual, my exact form of that “jump” isn’t the same as most others. Much of my hesitance in meeting people in the traditional ways, and subsequent general lack of success in this realm, has come a kind of fear of misperception. Short of wearing a sandwich board reading “no sex, please, and I’m not even Irish”, the mystification of that realm of human interaction makes broaching the subject in bald terms quite a challenge. Online dating, flawed as it might be, at least allows for an accepted degree of upfront discretion about these aspects of preference that most of us would be too polite to bring up at the outset of a potential relationship. Even in a city of 12 million, the chance of randomly meeting another of the roughly 1% of the population that is asexual is quite a remote one, so, we entrust our fates to the mystery of match algorithms and to the kind of honesty that keyboards and screennames allow. Between work and museums and concerts and an unfortunate incident of losing a wallet in a foreign country, I’d managed to schedule a couple of dates for the first 5 weeks, but both had fallen through in that odd way that makes you believe you did something terribly wrong without knowing exactly what it was. Though I would idly click about a bit whilst waiting for the train and tube, I’d basically given up the serious possibility of finding someone and was in a half-resignation of mere fun evenings for the rest of my time in the Great Wen. It was, then, though, that one of those hopeful digital bubbles came to me. Being a chronic self-doubter, I suppose I’ll always wonder what it was about me that stuck out for her, but, never also being one to argue with luck’s blessings, I was greatly enthused to meet up. It wasn’t the most auspicious of first encounters, involving a number of digital iterations of that London proverb “due to a train fault”, a rather bad in retrospect decision to run full-tilt to meet-up on a summer’s noon and culminating in a fainting spell (on my part) in the middle of the standing section of Shakespeare’s Globe. What I most remember, though, is, after that, her waiting with me in the heat stroke recovery room and the look of utterly genuine concern and empathy she wore. It was then I knew there was something to her, to London, to all of it, something that felt deeper, more real, than what had come before in my life. From there, I don’t think I’d ever seen or wanted to see so much of someone over such a short period of time. It is in that whirlwind of days out in parks, of nights of meetings for tea, that it was possible to believe in those mythologies of what big cities do to young hearts. It wasn’t New York, or Paris, or Rome, but then again, maybe I wasn’t, maybe we (if there was a “we”) weren’t those places. And, yet, just as quick, it was over; there were conferences in York, PHD theses at King’s College, degrees and bills and lives to go back to for the autumn. On the last time we were together, I felt only one thing had lacked resolution: I thought about kissing her, then I thought better of it, more hesitant, I didn’t. Maybe in a former age, I would have, not knowing if I’d ever have the chance again, but it is that same force of technological hope that assures us there can always be a “next time”. We can always message, instantly, and expect a reply within days at most. We can see the evolution of haircuts, event attendance, new victories and defeats at a not-quite-click of a touch screen. If we want, we can talk into the night on our sci-fi video phones that we strangely don’t recognize as such. In one sense, what might have been called “flings”, “summer loves”, now never have to end, the other person can always be there, with us, just a “hey, how are you?” away. In another sense, though, all things end and there is little sense in trying to deny this. Indeed, it is in the afterlife of sudden things that thought starts to actually focus on their meaning. Being swept up in the dodgy shade of Haringey evenings, of the utter impossibility of meeting someone you feel strong connected to in perhaps the world’s most anonymizing city, plays a funny trick of forever on the mind. It’s easy to believe that that technological advance holds our salvation, whether it be from climate change, car accidents or lonesome nights, but this ignores the fact that technology is crafted by human hands and, moreover, is used by them. New platforms promise us interaction that is more meaningful because it is more advanced. We have pictures and timelines and video and audio, but, in the end, the loss caused by distance still stings; clutching parchment to one’s chest in the night is scarcely different than doing so with an iPhone. It is often said that my generation has much of our love lives modulated by the ever-present hum of technology; too much, it is usually concluded. From the sudden ubiquity of Tinder’s rightward swipes as a symbolic representation of all that that it is to be dating and millennial, the outside observer might conclude that these loves are not so much of another person, but rather of glass and microchips. We are falling in love, lust or some ever-intermingled combination of the two not with the person before us but rather with what we perceive them to be in the self-editing funhouse mirror of the digital world. The sort of writing stemming from this hypothesis has a tone of nothing so much as the street corner apocalyptic, foretelling the end of human intimacy writ-large and the emergence of purely transactional relationship forms. Though this narrative is convenient, the facts on the ground, in the main, speak to something quite different. More than anything, technology is a perilous and imperfect scaffold we use in an attempt to transcend those borders which have always made a mockery of deeper plans. As long as human beings have travelled between places without the intent of staying, we have found these affections that have been characterized by a kind of mutually-known impermanence. The best, or rather less neurotic, amongst us, are able to embrace that impermanence as part of the thrill, or at least that is what they say. I often find myself thinking that if all the lost lovers between the invention of the human heart and sufficiently widespread DSL access had the option of adding each other on Facebook, most of them would. The feeling of being forever apart, or at least dependent upon the courage of the local postal carrier to fan a flicker of connection, can drive one mad, or else into the arms of the convenient nearby for comfort. It could be said that knowing these things to have a potential of being but once might have intensified the feelings involved, whereas now we draw back slightly, not wanting to seem uncouth or uncool. Air travel is a mass pursuit now and, anyways, can’t we express our true feelings some other Facetime? This same hesitance, though, impairs our connections. We draw out feelings: a burst of activity, but then rationed over those exchanges of canned reactions and phrases of our favoured digital spaces. I don’t know where, exactly, that leaves us in the wider sense. Perhaps we are doomed to exist in this between-space of lost and found as long as travel and technology hold out the hope of more permanent connection. Perhaps we can reconceive of love as something which requires less of a physical sense of “being there”. Perhaps, indeed, we can live again with the spirit of a life of interesting adventures and not hold too close to the glancing encounters. I particularly doubt the last of those, though. As for myself, when I finally gathered the wherewithal to really continue from that summer: I wrote a letter with an invitation to vacation together, I boxed it up with some particularly tacky emblems of Canadian pride and I sent it by post.  Bio: Carter Vance is a student and aspiring poet originally from Cobourg, Ontario, currently studying at Carleton University in Ottawa. His work has appeared in such publications as A Swift Exit, (parenthetical) and the Scarlet Leaf Review. He received an Honourable Mention from Contemporary Verse 2's Young Buck Poetry Awards in 2014. His work also appears on his personal blog Comment is Welcome (commentiswelcome.blogspot.com). 5/28/2016 Art by W. Jack Savage1)Remembering Who she Was 2)Above Bandiagara 3)Fish 4)Nearing the End 5)Suddenly It looked At Me Bio: W. Jack Savage is a retired broadcaster and educator. He is the author of seven books including Imagination: The Art of W. Jack Savage(wjacksavage.com). To date, more than fifty of Jack’s short stories and over seven-hundred of his paintings and drawings have been published worldwide. Jack and his wife Kathy live in Monrovia, California. 5/25/2016 Three poems by Flower Conroy[I had kissed] I had kissed The earth I had wiped my mouth With the back of my hand I inhaled My own rank Essence—sweat damp Sassafras & sawdust Punk & bluegrass Poured Myself a glass Of water Dirt from my lips Clouded the cylinder I bury What needs Burying The yard a catacomb Of ashes & glass This is not the poem that changes Water into ice Or ice into slush Slush into flesh This is not the poem of conversion Though if fed To fire it can perpetuate fire & its shape will be smoke In the shape of smoke What does it mean to dream of fishing Your hair out Of a well Of climbing a staircase As the bell Tower around You Burns Of God the Flower- Master Rasping Your opening The slow unwrapping Of a dangerous gift & to hear its echo You’re opening Slit rived ruptured gashed furrowed caesura gullied cleft interstice hairsbreadth Interspaced cleaved I divide I unraveled An orange Dug thumb dug Thumb- Nail into flavedo Dressed the pocked heart- Sized fruit Offering of rind & Seed Carpel Caked Under free edge Collecting The fibrous moss or Cloud or Cocoon-like Albedo & ate spilling In the fantasy gäd opens & Punishes me In all the fantasies the gäds Open & Punish me & I imagine God imagining me Being ready To punish Every disobedience So that I am a body Of distance & Obeisance When Your obedience Is complete The cold seabed island moon & I can’t keep Killing myself & not expect to die & Yesterday Belongs to ghosts & ghosts Are never Not Hungry & Once I tried To conjure a ship Wreck & my conjuring Conjured A pile of kindling & I walked out Into that moment Lightning Lashing At my back The moon hooked In its dark yard By its face Struggling To breathe This was no dream & Once I attempted To conjure a clouded Leopard & my conjuring Conjured Animal- Shadow From the corner A coyote Of ribs Slinked & I Walked out Into that moment & the fog blotted Swallowed the ground Only the gold Of its irises Searing then they Too disappeared & This was no Dream & I strove To conjure You & my Conjuring Conjured You Mastermind Muse Conjured Harelip the question Mark curlicues Of your locks as if You were haloed In ponder The quicksand Of your eyes You turned My face My face In your hand You Were Dream no Longer [If you are sitting] If you are sitting In a lit room & place your palm close To the wall Then withdraw It & bring it close again & Withdraw Your hand again Its silhouette’s outline Vacillates Between sharp & diffused Honed Becomes softened as light Diffracts inward Rays Spread Around your fingers My grief no longer Private But was it ever Mine Alone All waves Behave In this manner this is physics Not poetry The opposite of wind Sound curls beyond & Titillates your ear’s tunnel & water Displaced Splays around the hourglass Tossed into the sea Tossed into the sea The phrase Strike me No Not strike Strikes The phrase Tossed into the sea struck Me Untrue & Lovely I thought this was going To be about you [Dear Girl] But I’m not So sure Anymore Not sure Anymore who This is about & you Have been so good To me Listener Reader You the whitespace & the air Between the sheet & the eye You have been so good to me Watching me Watch you From the side This is not the passage that brings Back The dead But it may Bring The living Bring you Bring me Closer […] I meant to be rawer I mean to say this Stripped Of adornment The words Dressed As in skinned […] To say what needs To be said to the bone clean If it be Blood Let Me say Blood But never is that Never is space Only Space That wet Sound Is bay But may be a mouth Kissed By backhand Or fist As when I meant to rip Weed from foundation & my grip slipped & I popped myself Knuckles to lip & if it be heart- Sickness How can I call it Dearest reader Dearest listener By its name & not its halo One must write As if One were Already dead Meaning Without Space has no Vocabulary no Visible language My father composed The sky is up The grass is green Lots of air In between As joke As tease But I find myself too Often Contemplating that In between [The Bluer] The bluer The star The hotter The star That a name Is feared Because it is a real Power That it take possession of the water & pervade it That it be feral This is not the letter You read & re- Read Written in dead Language Words will not Deliver you The moon’s inanimate Basalt & Once I almost drowned Myself drifting Among insomniac fish Toward un- Consciousness Still dressed Going going going A word repeated I Finally Recognized As my own I was Beckoned back I was Hoisted up by shirt Collar & moist hair Words are proof ghosts exist A glass broken in the sink Indifferent universe What a strange machine Man is You fill him with bread Wine Fish & radishes & out comes sighs Laughter & dreams What about heartsickness Kanzantzakis How does one rid oneself Of the falling Upward Unrequited Lovesickness broken heart erotomania existential crisis possessiveness Obsessed limerence romancing the stone needy need It awaits hatching In your chest Until I can’t swallow Have you ever felt afar Like that Searching for Echoes In the cave Of your own breath A girl enters the forest Of suicides & cuts down The strung up Takes the rope As her own The life Of a star is one of slow transformation  Bio: Flower Conroy is the author of three chapbooks: Facts About Snakes & Hearts, winner of Heavy Feather Press’ Chapbook Contest; The Awful Suicidal Swans; and Escape to Nowhere. She is the winner of Radar Poetry’s first annual Coniston Prize and the Tennessee Williams Exhibit Poetry Contest, as well as a scholarship recipient of Bread Loaf, Squaw Valley, Napa Valley and the Key West Literary Seminar writers’ conferences. Her poetry has appeared/is forthcoming in American Literary Review, Gargoyle, Jai Alia and others. 5/23/2016 Two poems by Kenneth P. GurneySurplus Season Ravens live complementary to the highway. The roadkill the highway adds to the asphalt, the ravens subtract through ingestion. Their relationship is not perfect, in balance, zero sum. Four Degrees The ache my heart feels maps itself in the darkness as a dying star falls from the heavens. The echo of that ache burns like a half hour too long under the southwest sun. The shadow of that ache exists without words painted in the twitch my limbic system pushes through my cerebellum into my left wrist. The demonstration of that ache displays itself in the raised white skin of fifteen parallel lines cut across my right thigh.  Bio: Kenneth P. Gurney lives in Albuquerque, NM, USA with his beloved Dianne. His latest collection of poems is Stump Speech. His website is kpgurney.me.  “Clown Magic” For Misti Rainwater-Lites, Christopher Robin, and Zarina Zabrisky who told me to keep writing it out. by Aurelia Lorca I stood in the parking lot staring at the orange flowers and letters and the mint green and aqua blue panels. It was unmistakable. I kept rubbing my eyes. It was not a cartoon, it was not a plastic replica. I returned to my car in the parking lot of the grief counseling center, still rubbing my eyes. The van was parked cross the street in a driveway. The grief center had told me I was not a right fit for their services. I needed something more than grief counseling. I stood in the driveway rubbing my eyes. The van was not a cartoon. It was not a plastic replica. It was a real van, painted exactly like the Mystery Machine. I took a photo, and texted it to Misti. She texted back, “Clown Magic.” * * * Did I say I love you? I was on my way to a protest for the Ukraine in Union Square. Did I say I love you? I was late. I walked by you on O’Farrell and Powell across from Macy’s. I was late, and I was walking down O’Farrell, and the sun was so bright, you were crouched on the corner with a row of backpacks and someone’s pit-bull. Your face was so bruised and swollen I almost did not recognize you. I looked down and I almost didn’t recognize you because your face was purple. Like a big blueberry. I think I even gasped. You said hi but you did not smile. Everything was so bright, the sun was so bright, and your face was so dark. “What happened?” I asked. “Some guys at the bar next to our squat on California and Hyde didn’t like the way we looked,” you said. “They thought we had a knife, we didn’t. There were six of them and two of us. The bar called the cops- They knew we had been squatting there and not giving anyone any problems. The cops said we could press charges, but I didn’t have my id, and my buddy is on parole. So we didn’t.” I asked if you still had the jacket I bought you. You yelled of course and pointed to it on top of your backpack. “I didn’t sell it,” you said. “That wasn’t what I meant,” I said . “I just wanted to make sure you were ok, if it was keeping you warm. “ You were with Luna, your friend’s dog, a skateboard, and all of your backpacks. I didn’t know what to do or say. There was something larger than myself on that street going on- not just the protest up in Union Square that I was late to. The sunlight was so bright and there were people around. Whatever it was felt so big, and all was exposed. It was too big and too mushy to be on the street corner like that with so many people around. Your face was un-naturally bruised, and not just from getting beat up. I know now it was a sign that your heart was giving out. I gave you ten dollars. “You don’t have to do that,” you said, “I don’t want your money.” “Please,” I said, “just be ok.” I was running late to a protest. My friend Zarina also was once a junkie in Russia and knew more dead than the living, I wanted to support her. The world was bigger than my heartache. I was running late, so I asked you to come with me and you said you couldn’t but you would meet me later. There was something I had to say. I think I said it. I said I love you there on the street corner, on O’Farrell and Powell. Once upon a time it upset you when I said I love you too much, but I said it there on the street corner, even though it felt so weird to be so vulnerable like that. I didn’t think it would be the last time I ever saw you. I just needed to say I love you because your face was so black and blue. I didn’t think it would be the last time I saw you. I just wanted you to know that I loved you. You told me that you’d meet me later, that you had to wait for your friends, that you couldn’t leave their dog and backpack, that you’d come to the protest, but it was the last time I ever saw you other than in my dreams. * * * Sunday, Easter morning began in mist. I sat in a cafe staring at my coffee. I could not think, I could not pray, there was only silence and the mist outside that had turned into rain. The streets had become silver and still. It was Easter morning. A car passed outside and the rain flew under its wheels in a glittering spray. I had not noticed that the cafe was playing music, until a song started playing, “Aint No Sunshine When She’s Gone.” Everything inside of me is muffled, like a calm before the storm. Outside more cars passed by, passed through in the silver silence of rain. I wanted to scream, but could not find the words. And the song played on, “Ain’t No Sunshine When She’s Gone.” I stepped outside. The streets were silver in rain. * * * It had been unreal: On Good Friday, April 3rd, at sunset, the night before the blood moon, a man’s voice left a message from an unknown number, “This is an emergency phone call, I have some very sad news.” The man identified himself as the San Francisco Medical Examiner and asked if I was next of kin, did I know next of kin? You died on April Fool’s Day. I was waiting for someone to say April Fool’s. I kept replaying the message. I have some very sad news. I have some very sad news. I have some very sad news. I have some very sad news. I have some very sad news. I have some very sad news. * * * The weekend after you died I found myself in Santa Cruz, and saw Rusty’s garden. Rusty was your little sister’s cat, and after she died, he became your cat. You loved to imitate his hyphenated meow and his goggly lazy eyed stare. Though you had to leave him behind, you loved Rusty, and though you wanted to, you just could not take care of him anymore. Whenever you spoke about Rusty, you would almost begin to cry, but you would insist how Rusty had a large garden to play in. “That garden is like a jungle for him,” you would say. “He loves it. He is so happy. It is the best thing for him.” A week before you died, I learn that Rusty passed away at 21 years old, 101 in human years. When I finally saw Rusty’s garden, I realized it was exactly what you wanted for all of us: A giant lemon tree with its overgrown branches and bright fruit, and even a spotted bunny hopping about with one sad chewed off ear. I was told the garden wasn’t as wild as it once was, but I am sure Rusty was as happy as he was loved- he even had a little grave marker that says, Rust In Peace. I walked back to my car from the garden, thinking to myself, “ok, I get it, I get it, you want us to find a garden, live a long life, surround ourselves with love, and be happy.” Easier said than done, I thought as I got into my car, and turned on the stereo. For some reason, out of all the songs on my itunes, Motorhead’s “Overkill” came on, as if in agreement with my epiphany, and adding, “only way to feel the noise is when its good and loud.” * * * Even Christopher Robin, who coined the phrase “clown magic” told me as we drove down Pacific Avenue that you were a nice guy, but a junkie. I couldn’t expect you to change overnight, or a weekend. “You don’t get it. This is heroin addiction we are talking about,” Christopher Robin said slowly extending out the syllables. “Clown magic,” I said. We were at a stop light, I pointed to the left across the island of Pacific Avenue. “That’s the Chinese restaurant he said he squatted at.” Christopher Robin squinted and said, “And isn’t that him, standing out front?” Indeed, there you were, holding a giant 7-11 cup and gaping at us from across the street. I honked and waved you over. You paused like you were considering something, and then nodded to the guy you were standing next to. * * * I had not forgotten you though it had been years. You had been a hard-core punk with dimples, a chipped front tooth, a little fleck on the chin, dyed maroon hair, and brown skin. Usually your smiles were smirks, and you held your face into a scowl, because when you really smiled you showed your dimples. I was an undergrad at UC Davis who was supposed to be studying literature, but felt more comfortable in the punk subculture of the townies than in a classroom. You had an old white volkswagen, and was working as a cook at a brew pub. You were one of the few punks in town with a job. As you drove us to get beer, I read to you Matthew Arnold’s “Dover Beach,” but I was someone else’s girl- another punk who was in and out of prison. We hung out a few times but then you left Davis because you were using too much speed. You came back to visit, and my boyfriend said to us, “someone’s getting their ass kicked tonight- either you, or her.” You said, “then I guess that will be me,” and took a beating to get him out of my apartment. I had never forgotten you. I had always wanted to say thank you. * * * “This isn’t going to work,” you said after you decided to leave Santa Cruz and move to San Francisco. “We come from different worlds, but your world is saving me.” “Clown magic,” I said. “Clown magic.” I was very drunk when you finally kissed me. “I love you, I love you, I love you, I love you,” you said over and over again. * * * You got a job, you found your own place. You said you were one of those who didn’t know what it was to be “in love” but you smiled whenever you thought of me. “Is that love?” you asked. “I don’t know what love is.” I couldn’t tell you anything other than I was a poet who believed in clown magic- That the divine order universe would always offer poets what they needed to understand any situation. And yet, I was also one of those who took umbrage that your cynicism might have something to do with me. It began to be there was nothing you could say that was not something else. Sometimes I would argue myself out your door, whining- “I’m not trying to be pushy or anything.” But you knew I would be back. I would always come back. By 3am I would send you a text. “I’ll take you to work tomorrow,” I’d say. “If you want,” you’d reply. And the next day, I’d be there waiting for you to be ready, accepting everything as if it hadn’t happened. * * * One of the last times I saw you, you said how he had made a mistake. You smelled not just of the streets but of rot. I let you give me a hug, and for hours after I thought I felt my skin itch and hated myself for it. * * * Every night when you first came to San Francisco I walked with you to Union Square. It was around Christmas time. We watched the sunset spin haloes around the Statue of Victory pillar as the neon lights of the ice rink offered a warm glimmer to the night. The giant tree was a freakish beacon we watched from hard benches, the ornaments enlarging our raised eyebrows. Joy spangled the heavens onto our hands. The trumpet flowers dangled over the metal benches and offer an umbrella of winter perfume and the palm trees were fringed in tiny holiday lights giving the appearance of sparkling eyelashes. We watched it all from hard benches softened by the thousand lights of the giant tree. We saw only sparkling and the Statue of Victory pillar that drowned the ornaments and all else on the edges. There was a world that existed beyond the edges, a world beyond the moon-like glow of the ice rink, and the bad-assed brilliance of the giant tree that created a couch from a metallic bench with a dazzle and a pop and awestruck faces as victorious as Victoria atop the statue of Victory pillar. And victory was as victory decided, amid glowing ice rinks, giant trees, hard benches and faces, and pillars that reminded us to be. I was very drunk the first time you kissed me. You said, “This is never going to work.” I told you, “Clown magic. Clown magic.” You said, “I love you, I love you, I love you.” * * * The nights with you all bled into one another leaving only a texture of words. I remember skipping down California Street backwards because you told me cable cars were over-rated. On another night, the night we were going to an art show on Hyde Street, I shared a fifth of Grey Goose with you while playing on the swings in a park on the top of Nob Hill. “I need to smoke a cigarette before going,” you said. “Ok,” I said, hoisting myself onto a ledge. The gallery had giant windows and clusters of bright haired people wearing black clothes and funny facial hair. “It looks kinda crowded,” I said, peering through the windows. “Check it out through the windows- S&M graffiti art inspired by the Folsom Street fair.” “Who’s your favorite poet?” I asked a hipster with an ironically unfortunate mustache going into the gallery. I was drunk, and feeling obnoxious. The hipster fingered his mustache and shrugged. “I’m not going in there,” you said, putting out your cigarette. “It’s a bunch of pseudo graffiti art and hipster fucks.” I pushed myself off the ledge and went over to a water spigot outside the gallery. “Who is your favorite poet?” I asked it, wrapping my fingers around the nozzle. “I’ll tickle it out of you like water!” You smiled and your mouth dropped open. “No matter what you do or say, no matter what happens, I will love you forever.” “Clown magic,” I said. * * * Christopher Robin lived in Santa Cruz in a small Section 8 apartment off Chestnut Street near the Boardwalk that distinguished itself in an array of toys, records, tiny pinball machines, small press posters, and type-writers. “Be careful of the typewriter on the sofa,” Christopher Robin told us the day we went back to his apartment after I found you on Ocean Avenue. “I gotta work in the next room.” Three cabbage patch dolls were sitting on the floor, along with a plastic replica of the Mystery Machine from Scooby Doo. An assortment of books and a happy meal toy of the three little pigs were on the coffee table. You put your fingers lightly on top of the Mystery Machine, “What is this place? Are you sure it is ok if I am here?” “Yes, this is my best friend. He’s also a poet, and an ex junkie who was so fucked up that he got kicked out of clown school. He got clean in jail on the day Bukowski died. Anyway this is Zen Baby headquarters. He used to have the poetry reading at the Wired Wash and after everyone would come over here to hang out. For years he did this cut and paste punk poetry zine called Zen Baby. But now he’s become a picker, a junk man- hence the cabbage patch dolls. Christopher Robin, of course, is not his real name. His dad was from Sicily, and his real name is very Italian, but no one knows what it is. He’s been called a whole host of nicknames- Spook, Mouse, Eddie, the evil dark overlord of Duh…” You wrapped yourself into a blanket, stretched out onto the sofa. You put your head underneath the blanket. Your body was shivering. “How do you know this guy again?” “Through poetry,” I said. “The small press.” I picked up the three little pigs happy meal toy on the table. I pressed the stomach of the middle pig. “Yahhh!” it said in a German accent. “What the fuck is that?” you said from under the blanket. Your voice was soft and amused. The I pressed the little piggy again. Again it said, “Yahhh!” “It’s this happy meal toy Misti Rainwater-Lites sent to Christopher.” “Who or what is a Misti Rainwater-Lites?” You said, still under the blanket, and lilting the consonants of Misti’s name. “Another poet. My sister of dangerous hair. She lives in Texas but came out last summer for a week and stayed here at Christophe Robin’s when he was out of town. We’re starting our own church- Saint Rooster Toot’s, patron saint of the absurd. Except we don’t have a chapel, we only have karaoke bars. I pressed the stomach of the middle pig again, it said, “Coochie cah.” I pressed the piggies again. “Puddin’ pot” they said.. “What the fuck is that thing?” This time you were softly laughing. “It’s a happy meal toy!” I sat down on the sofa next to you. The type-writer wedged against my back. “Eeyyyah,” the piggies said as I pinched its stomach once more. It sounded just like the first “yahhh” but it was longer and more accented. “Yahhhh,” you said, and sat up from the sofa. You pushed back the blanket you were wrapped in, and your body straightened out against the length of the couch as you began to really laugh. You shook your head, and reached out for the toy, pressing its belly and making it cry out in it’s accented, “Yahhhhhh.” You were still trembling. “Do you want a hug?” I asked. You did not look at me, but you cuddled my head under your chin and said, “Now I feel at peace.” I fell asleep with your arms wrapped around me, looking at the blues and greens and oranges of the toy Mystery Machine van beneath the sofa.  Bio: Nicole Henares (Aurelia Lorca) is a poet, storyteller, and teacher who lives in San Francisco California. She has her BA in English from UC Davis, her MFA in Writing and Consciousness from California Institute of Integral Studies, and is an alumna of the Voices of Our Nation Writing Workshops. She is interested in how Lorca’s duende, the duende of Andalusia and flamenco, is a cross cultural spirit. 5/18/2016 Three poems by David Ross LinklaterChimera Each drop drumming the tin roof I jar the window and light a cigarette My left leg is bald beneath the knee The drunk howls like a dog Tethered to streetlight My fingers are of burns and rag nails He is singing songs of battle One hand raised into the quiet rain A bone wrapped in leather flag I stub my cigarette in a clump of moss And listen to it fizzle and die I leave the window open Wondering causes of baldness His voice breaks with fire I hear a bottle smash The sound of sirens and laughter I pull the curtain as the geese pass And sleep dreams of fishermen climbing Hundred-foot waves Blue Moor I have moved the bed and now make myself in its corner, counting false summits of blue quilt. I see myself climbing peaks, edging along thin pathways with rope railings, stopping to rest on wind-bitten walls wary of bulls. In this smoky room I’ve walked the dog Balmuchy to Ypres, placed fields on a shelf and watched horses dance in mirage. I’ve barely touched ground in orange cities, penetrating lime back alleys and barbed tongues. I’ve wrapped thoughts in bundles—I keep them in a store room with the negatives. Somewhere under boxes of old Augusts and oranges are the landscapes and people from them. Tonight with this quilt I am walking there again. Until the bed is made, hills spread to blue moorland. Moon Slice I have nothing to do cigarette Burns again The window broken For its lack of originality Place the night on the chopping board Open it up bleed it Drain ‘til it turns white Go beautiful falling into patterns Spat my heart against a wall Slid down and dried out like a fish The scales were really glistening Turn off the light Tilt his head in case of vomit Get off your high horse and go to bed The moon is swinging like a scythe  Bio: David Ross Linklater is a poet from the Highlands of Scotland, now living in Glasgow. He is currently studying a Masters in Creative Writing at the University of Glasgow and is working on a collection of poems. His writing has appeared inGlasgow Review of Books, The Grind, The High Flight, Ink, Sweat & Tears and RAUM, amongst others. He digs watermelon. Review of Jessie Janeshek's Spanish Donkey/Pear of Anguish Ever wonder what would have happened if Kathy Acker and Flannery O'conner had collaborated on a book of poems? The result may have looked something (although nowhere close) to Jessie Janeshek's latest book 'Spanish Donkey/Pear of Anguish.' Comparisons aren't fair in any case, this is especially true here, as Janeshek is in full control of the place that she wants to take you, a place that once took control from girls is now reclaimed, taken by the throat until the place has pissed its pants, so to speak. These poems will leave their mark on you. Between “A priest wet with piss” and “piss-soaked pages” “we start from an amazing place of decay” Janeshek writes. Not only can “sex be toxic” but the landscape too, the farm animals, dark pigs, deer carcasses, chickens, skulls, foxes, pigpens, jack rabbit, dog, cat, baby, and a “Dark Uncle Thick sits upstairs, ballgame on our parents spit bullets over bad plumbing.” The sex is toxic, messy/confusing and made even more difficult-enraging by the control adults exert, by their hypocrisy and blatant contradictions “you have a wife but you laugh as you lick us” “and we hate ourselves and we hate our body but we love draft beer and the lord.” “Money's symbolic sex is symbolic.” The holy relics can be replaced “w/ any old skeleton” as these puritanical objects are just a column that the self-righteous use to hide their own mud soaked back yards of misdeeds. Janeshek calls it all out for what it really is: “using the bible to hurt other people” and all of this within the very first poem “we masturbated with a glass eye one slimy finger We twisted our wrists virile tidbits” there is this indestructible lightning quick resistance pulling the rip-cord off the curtain of generational bullshit. “And, yes, we get caught since if not guilt then what?” A profound punch, it leaves its bruise but you better believe its spot was well marked in advance, Janeshek knows exactly where she wants the blow to land, and it is devastatingly quick, biting and to the primal core. “We validate your subjectivity strive to seem warm but not kittenish pull red poison yarns out of our nipples.” The stifling male dominated expectations of femininity are deconstructed here with brilliantly biting humor, and then the stark-dark realism of this place: “We still have one bad calf's white corpse in the basement. Can you help us bury it.” “We walk abroad in humility shovel fresh shit, rub hands together, servile, Pentecostal. We're tired of sharp badges, high tests, blind pines... no pledge of allegiance. You'd never have treated us this way in the old days” Janeshek writes in “The Clouds of the Father, Part 2” signaling the dark storms that generations of Fathers have been dragging into the future with them, handed down to their kin as if it were a fatal flaw that could not be un-owned, but Janeshek not only refuses to own it, she refuses to let us off the hook for all of the reasons why this is continuing to happen. Why so many damaged-clouds these Fathers keep giving? What is their source? The political hypocrisy. “Witness humanity fixing our uterus our lagging muffler” as if a womans body can be broken down into car parts, as if the mechanic/politician, as full of shit as the “priest wet with piss” has any authority except that which he has laid claim to through outright coercion and abuse, through inter-generational erasure and shame tactics. “Then science gets interesting seances in jars” a hard jab at the wind pipes of the religious hijacking of women's bodies. “I think I hear you coming but it's just the sheepdog.” Janeshek once again returns us to that early landscape, even in the heart of the political moment, precisely because it is all connected, and she wants us to know that she knows what we want to pretend not to know, that we are all implicated in this world, that none of our hands are clean. “The medicine's empty, but we drink it anyway sing to distract.” “It's not crime if it's habit” the delusions that we all participate in and pass on would almost have us believe. But it is crime. A shared crime. And our habit is here exposed in all of its fleshy messiness. Spanish Donkey/Pear of Anguish is pure punch-poetry, it never misses a beat and it certainly never misses its mark. Read this book and be changed. Or better yet, read this book and change. Spanish Donkey/Pear of Anguish by Jessie Janeshek, published by Grey Book Press, can be purchased here: http://greybookpress.com/index.php/site/titles/  Bio: Living in the picturesque(ish) town of Wollongong, Australia, Gracie Delaney is an artist, photographer, writer, and all-round head case, who regularly discusses the meaning of life with the small commune of native birds who reside within her dreadlocks. An idealist at heart, Gracie constructs her work atop two basic principles: the first, an unending love for the imagined, and the second, an unwavering belief in our God-given ability to look beyond the bounds of the mundane, and see with more than just our eyes. You can find her on DeviantART (http://sparki111.deviantart.com/) and Instagram (@gracie.alexandra) 5/14/2016 Photography by Russell Streur  Bio: Russell Streur’s poetry has been widely published in the United States and Europe. His work is most recently included in Negative Capability Press’s 2015 anthology of Georgia poetry, Stone, River, Sky. Streur is the former editor of the world’s original online poetry bar, The Camel Saloon and is the current editor of Plum Tree Tavern ( http://theplumtreetavern.blogspot.com/ ). He is the author of The Muse of Many Names (Poets Democracy, 2011), The Table of Discontents (Ten Pages Press, 2012), and Fault Lines, forthcoming this year from Blue Hour Press. An avid photographer, Streur is a member of the Atlanta Artists Center and the Atlanta Photography Group. His camera work is seen in the eco-poetic journal Written River and other print and online publications as well as the Grandview and Tula Galleries and other venues in the Atlanta area. |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

April 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed