|

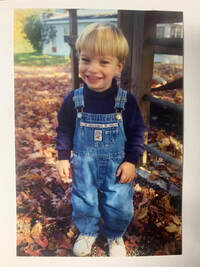

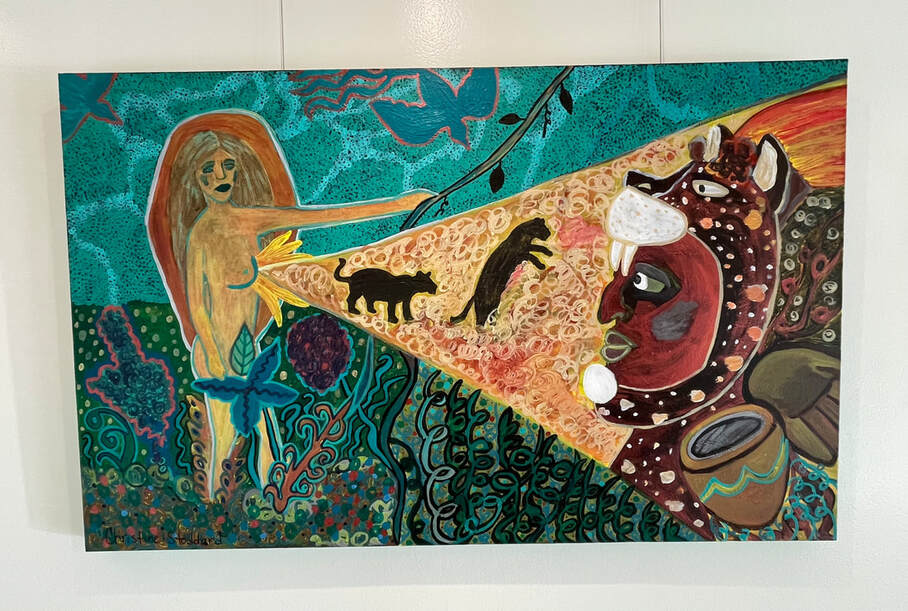

3/31/2024 Our Wild Thing by Amanda Kernahan Viktor Rutberg CC Our Wild Thing The grainy photo appeared in my social media feed, a post shared by an acquaintance, created by a news station, captured by low-resolution cameras inside a bank hundreds of miles from my home. I knew it was him, my baby brother walking out of the bank in an oversized hoodie pulled over his head, his shoulders slumped, eyes down. Through the screen and pixelated image, I could feel his despair coming through the phone and filling the air around me. He was wanted for robbing a bank, the same crime our older brother was sitting behind bars in another state for committing. I had seen James slowly disappearing for years, watching helplessly from the land of “loved ones,” a place I have inhabited as far back as I can remember. I sat in my living room, stunned silent. I couldn’t make out his thick mop of hair beneath the hoodie, but I wished I could put a hand into it and hold him against me in a hug, give him the love I knew he would never find in the drugs he was seeking. James’ blonde hair had always been untameable, thick like hay, repelling water before finally absorbing it. His spirit as untameable as his hair. As a little boy, he would snuggle into our mother’s side at night and read his favorite book- Where the Wild Things Are. James loved the story of the boy who would romp around with the Wild Things unafraid, coming home after his adventures to the safety of his bedroom. The paperback grew ragged from love, creased and worn as little fingers with a mother’s gentle guidance turned its pages over and over again. Our mom lovingly called him her “little Max,” or her “Wild Thing” when he was especially mischievous. As he grew, he would gallivant fearlessly during the day, whipping through the trees on his dirtbike with mud speckling his face and covering his clothes. The youngest of four siblings, James craved independence and adulthood from an early age, languishing behind the rest of us in various stages of dating, driving, and college. Mom gushed over him as her baby, a term often met with terse lips and an eye roll. As he ventured into his teenage years he put up a tough persona, a shield never strong enough to hide his sensitive child heart from those who knew him. His maturing age never stopped our Mom from sneaking little Wild Thing stuffies onto his bed- permission to remain a child, reminders of love. He was staying at my house one summer morning when I got the phone call ending with three terrifying words- “Baby, she died.” Our 47-year-old vibrant Mom whose love language was laughter and practical jokes, petite in size but giant in personality, had died without warning. Sitting in a pale green oversized chair in her living room a heart attack stole her away in the dark of the night, her dog whimpering at her feet. I knew before my brothers, having to face each of them and break their hearts one by one. “Mom died,” I said softly, wishing I could withhold the agony I knew I was inflicting. James' 15-year-old face fell, the emerging adolescent mask of toughness revealing the truth- he was still just a baby, her baby. Grief swallowed us up swiftly, our attention consumed by our own individual pain. We barely noticed as James sailed away to the island of the Wild Things, looking for a comfort this world did not seem to provide. The island was full of other lost boys and girls, new friends who loved him, and enough drugs to numb the pain. When we realized he had gone, we were desperate to get him back. Perhaps if we just love him enough? If we cry and beg? If we force help upon him? If we pray to a God we don’t believe in because he already stole our mother? Our love, enough to fill an ocean, was not enough to bring him home to us. The island held him there, captive yet unaware. He wasn’t the first of us to visit that place, our oldest sibling had resided there for decades. He had come home on and off over the years but our mother’s death was enough to summon him back, James following quietly behind. Addiction had always been an island I couldn’t reach, the Wild Things terrified me. Learning about drugs from the D.A.R.E. officer in my elementary classroom, I naively thought saying no would be enough. He didn’t warn us that drugs could find their way into your home, into your blood and your marrow, without ever ingesting them. He didn’t explain that the dark and dirty criminals he described were actually just people’s brothers. Siblings they had grown up riding bikes with and splitting the mounds of Halloween candy strewn across the living room carpet in pure sugar bliss. “I will trade you 2 Snickers for 1 Reeses!” When James followed our older brother into this land I had never stepped foot in, I stood and watched the waters retreat from me, waiting for the tsunami. We tried everything from the shore. We hosted an intervention on the porch of my aunt’s house, where I looked him in the eye across the weathered wicker table and croaked out, “I don’t want you to die” before tears closed my throat. We forced him to go to rehab in hopes it would bring him back to us. We loved him. Angrily, fully, desperately. He loved us too. None of it was ever about a lack of love- it was neither the problem nor the solution. For 7 years James lived in the land of the wild things, visible to us but out of reach. Addiction infiltrated him like a poisonous moss his bare feet padded in search of a soft landing- only to find it grew tentacles, wrapping around him and refusing to let him leave. Every time I saw my youngest brother, I could see a little boy unable to make his way home. I knew the home he was searching for was our mom, an echo we could no longer access. She was in the space between us, not in the realm I walked or the island James lingered on. We each raged in our own ways at the unfairness of it. Sitting on my couch staring at the blurry security camera image, I knew it was him instantly. I knew him from the contours. Low-quality photos cannot hide from us the things we love. We need only the silhouette, one piece of the puzzle we know so well. I told no one, retreating within myself, the only island I have ever felt safe on. I nearly drowned in anxiety waiting for an outcome. It came several days later with his arrest, our beloved wild thing contained. It took time for the drugs to dissipate, to give up on their host unable to feed them. A judge mercifully sentenced him to a long-term rehab program rather than jail. Slowly, James came back to himself, to us. No longer the 15-year-old boy sailing away, he was now a 23-year-old young man daring to look into a future here among us mortals. He began to read. First of a bird named Jonathan Livingston Seagull, learning to fly as an outcast among his peers. As his fervor for reading grew, I sent him my favorite book- Wild by Cheryl Strayed, proof that so many of us are lost wild things in search of the way home to ourselves. As he devoured books and pondered things like inner peace, I dared to reacquaint myself with hope. James left the rehab center to begin again as temperatures rose into summer, the sun visiting for longer hours each day, the dark season retreating. His thick blonde hair was buzzed short, a soft fuzz in its place. He chose to live on a wide swath of land that belonged to our uncle, in a camper set among trees and grasshoppers. A home in the beautiful wild. A crackling campfire he could watch dance just outside his door. The island he had once frequented seemed a distant memory for us, but it still beckoned him in the dark. On a warm August evening, he returned to his home among the wild things. A place that would eat him up and never let him go again. Another phone call brought me to my knees. I stood on the shore with my family, anger and sadness pouring out into a sea of tears. His joyful laugh and mischievous smirk, his vast future potential, the children he never had and the wife he never met, all extinguished. It has been 6 years since my brother James was reduced to ashes, 14 years since our Mom was lowered into the ground. Federal prisons across the country are the ever-changing home addresses of my older brother. We have been scattered like the tufts of a dandelion, all beginning from the same stem. I still think about all of the wild things and all of the families who hope they come home for dinner. Max, King of the Wild Things, swings from a branch surrounded by flowers and a pinecone on my upper left bicep. My other brother Shane carries Max hoisting a royal scepter on the back of a Wild Thing over his right lower ribs. My husband has him in a boat, sailing a rough sea on his arm. Ink seared into our skin, scars we keep visible for the world. We romp around and adventure, taking him to the mountains, on airplanes to distant places, to warm sandy beaches where our children run into the waves with wild abandon. We stand at the shore, toes in the sand, wind in our faces. We look out at the faraway unknown and whisper, we love you so.  Amanda Kernahan is a writer, host of the Grief Trails podcast, founder of RememberGrams, and a proud Adirondack 46er. She has been published in Slate Magazine as well as The KeepThings, and is working towards the publication of her memoir about grief, loving those with addictions, and seeking solace in nature. Find her on Instagram @AmandaKernahanWrites or on Substack @AmandaKernahan. She lives in Rochester, NY with her husband, two children, and their big loveable German Shepard 3/31/2024 Smeared by Bethany Bruno Bill Reynolds CC Smeared I wipe between my sticky thighs, finding bright red blood smeared across the toilet paper. “No, no, no,” I mutter in rapid succession, as if speaking words aloud will somehow make the blood disappear. Disappointment sweeps across me like a sudden burst of wind on a still, cloudless day. I bunch up more toilet paper and swipe once more. When I bring it up to my face to examine it, I shudder. There’s no denying the evidence of my failure this time. My face flushes with the rising heat of shame. With a single flush, another hopeful wish to be pregnant circles the drain, leaving me empty. It's a constant, unavoidable presence every twenty-eight days. For nearly twenty years, I’ve merely accepted its arrival and made do with flexible tampons and the occasional popping of Pamprin to dull the cramps. But that all changed one year ago, when I decided I was ready for my next baby. Based on how quickly I became pregnant with my daughter, I naively believed I would fall pregnant within the first two months. Now, after twelve periods, my faith in my ability to conceive has dwindled. My womb became an hourglass the minute I stupidly timed myself. But instead of flipping it upside down, I’ve had to endure the agony of watching every particle of sand drop onto the growing pile below. I’ve come to dread the sight of blood, whether it’s mine or someone else's. Last month, I woke up to the familiar sensation of wetness pooling in my underwear. The unmistakable smell of metal makes my teeth ache as if I were chewing on tinfoil. In the darkness of my room, with only slivers of sunlight peeking through the blackout curtains, I stripped off my clothes and rushed into the warm embrace of my steaming shower. I stared straight ahead at the blue and white tiled wall, afraid to look down at the swirling pink water. But, after toweling off, I made the rookie mistake of hanging up my white towel on the back of the bathroom door. As I reached for the doorknob, a tiny smear of blood stared back at me, taunting me. My husband and I have sex every other day for one week each month in an effort to end the cycle. Sex has become a necessity, much like keeping up with the growing mountain of dirty laundry or taking out the diaper genie trash bag once it’s brimming with poopy diapers. A physical dance between us where both partners no longer grin or twirl around with giddy laughter. “Here,” I thrust the blue ovulation test toward him, “do you see two red lines? I think it’s positive.” He squints while peering intently at the thin strip. “We should have sex just in case,” I tell him, which feels more like a command than a suggestion. During the act, we kiss as the impending, dreaded question penetrates our minds: Will this be the time we make another baby? In the days leading up to my expected period, I tell him, “I think I'm pregnant. I just feel like I am, you know? My boobs ache, and my abdomen hurts.” My husband is used to this old song and dance, having heard it many times in our efforts to create a sibling for our young daughter. He never challenges my “signs” or intuition—the very symptoms that, ironically enough, foretell a woman's upcoming period: bloating, cramps, mood swings, and cravings. He simply smiles and says, “That would be great.” Though he’s never hinted at it, I worry he’s beginning to resent me—or at least my body. I couldn't possibly hold it against him if he did, since I share his sentiments. In truth, I’ve never had a positive relationship with my body, having been overweight since middle school. My small breasts never rounded into perfect mounds and instead, even after my first pregnancy, still resemble dulled edged triangles. Yet, my body always maintained the status quo of work production. It’s never completely failed my expectations—until now. I picture the inside of my uterus as a shuttered factory, with workers scurrying about under the flashing red strobe light. No matter how hard they hustle, the assembly line is never offset. On the day before my expected period, every fiber of my being vibrates with nervous energy, like a cornered animal ready to chomp. I know I can’t force my uterus to grasp onto the fertilized egg, no matter how hard I push with every available herb and supplement “known” to help with conception. Even my OBGYN is frustrated with my body’s inability to cooperate. Every appointment ends with the same phrase: “Continue taking X along with a balanced diet, and we’ll try again.” I spend the day stuck in a tornado of uncertainty, often ignoring the child that’s seated next to me on our couch as she howls with laughter while watching “Bubble Guppies.” The end goal of creating another baby has consumed my life. It’s slowly chipping away at my marriage and my budding relationship with my toddler. I imagine this obsession with winning is common among athletes intent on proving their worth to the world. Their gold medal is my positive pregnancy test. At thirty-five years old, I don’t have the safety net of time. I plead with my body to work with me, but she’s a stubborn mule. Rather than depend on nature to nurture me, I have begun taking matters into my own hands. My secret weapon is a fertility drug called Clomid that I’ve been taking for the last two months. It stimulates my ovaries into releasing multiple eggs, upping my chances of conception. I imagine it to be like a t-shirt gun, with both ovaries firing eggs simultaneously as the sperm cheers. The downside, though worth it, is the immense mood swings and emotional outbursts. Anxious irritation strums throughout my body as if someone is striking a guitar string. But my desperation to conceive far outweighs it all—at least until I reach my limit. With all of the questions and uncertainties comes the possibility that it won't happen. For some women, of which I’m now unwillingly a part, conceiving a second pregnancy can be damn near impossible. Recently, when I picked my daughter up from my aunt’s house, she blurted out her opinion freely. “I hope she gets a sibling,” she said as we watched my daughter stack her rainbow plastic cups into a tower. Since the day my first child was born, I’ve heard some variation of this opinion from nearly every family member: When are you having another? Wouldn’t it be lovely if you had a boy next? Is baby number two cooking in there already? I tend to laugh it off with a wave of my hand, as if shooing away a pesky fly. “We’re trying!” I say it with an awkward smile. Yet, at that moment in my aunt’s house, my tolerance boiled over into nuclear level anger. I was about to lay a verbal smackdown when she spoke up first. “We tried, Walt and I,” she said with a sigh, “for many years. But for whatever reason, I couldn’t get pregnant. Nowadays, they have all sorts of options available that were not back in the seventies.” She turned to me and gave a sad smile, saying, “It’ll happen if it’s meant to. And if not, then at least you have Frankie. She’s enough.” As empathy flooded in to replace my hurt, I released the reins of my anger. Millions of women, both past and present, share my struggle. But when you're down in the muck, you tend not to look around you at the others trying to pull themselves out too. The happiness and fulfillment I experience as a result of being a parent to my daughter have never been in question. She’s more than enough. The real question is, Why do I believe having another child is essential to my own and my family's happiness? In addition to my daydreams of what having a family looks like, there’s the societal ideal of marriage and children. Women aspire to have it all, believing that doing so demonstrates our value to society. We want all areas of our lives to be exemplary, whether it’s in our marriages, families, or work. The key to “having it all” is realizing that you already have it. But acceptance of that key doesn’t mean resignation from my goal. My period is currently expected within one week. That feather of hope about being pregnant floats in the air, occasionally dancing around me thanks to a gust of wind. It’s dangled in front of me, as if teasing me with anticipation. Until then, I give myself permission to cease my mind's pacing. I will no longer be urinating on those flimsy ovulation and pregnancy test strips every day in an effort to calm my nerves. I’m not throwing in the towel. I’m asking the fertility referee for a water break to swish and spit my overwhelming uncertainty into a ringside bucket. Only time will tell on arrival day if there’s a smear of blood or a positive pregnancy test. If my period arrives, disappointment will still undoubtedly crash into me. If I’m pregnant, I’ll sigh in relief and fist pump the air—at least, this is what I imagine doing. Yet a positive test doesn't necessarily mean the enormous weight is off my chest, as there are a number of issues that could occur, including a miscarriage. It's like the moment your plastic marker leaves the starting line in a board game and you're confronted with an infinite number of side-quests. You’re happy to finally move ahead, but there’s still an entire game to play. I'll play it all the way through to the end, or I'll call it a day and put it back on the dusty shelf in my closet. Either way, I played, and that is enough for me.  Bethany Bruno is an Irish-Italian American writer. She was born and raised in South Florida. She obtained a BA in English from Flagler College and later earned an MA from the University of North Florida. Her writing has been previously featured in several journals, including The Sun, The MacGuffin, Ruminate, Every Day Fiction, The First Line, and Lunch Ticket Magazine. She was nominated for Best of the Net in 2021. She’s represented by Caitlin Mahoney of the William Morris Endeavor Agency. Her debut novel, "Tend to the Light," is in the final stages before publication. https://www.bethanybrunowriter.com 3/31/2024 Morning-After Email by Brenna McPeek Danny Navarro CC Morning-After Email In college they called it forcible touching, which seems coy to you now in an age where everything is a slap in your face, and it was a skin-crawling thing, this touching—no, wait, not was but is because it still happens all the time despite the sallow spotlight we’ve since shined on it; let’s just call it out for what it was to you at the time: a bad thing, a Terrible Something you didn’t want to put a real name to, though we can all guess what Terrible Something we’re talking about because we’re all women here, and while there are many bad things that can happen to a woman there are only a few truly Terrible Somethings and your university used to send them out to you via “petty crime reports” (pussy crime reports, everyone called them back then behind the school’s back) over email on Thursdays, Fridays, Saturdays, or any night really where inhibitions were down and boundaries discarded, meant as warnings, you think, but they read like bad after school specials: Caucasian male, age 26, medium build in a hooded sweatshirt, approached a female co-ed walking home from the bar, forcibly touched her breasts and her groin, ran only when she screamed; on breezy Sunday mornings you and your roommates would read these scenes aloud in dramatic fashion, hungover, crying laughter, and mainlining coffee or Adderall or coke to help you do your studying or drinking or whatever it was you used to do before you had Real Life problems, before you realized it wasn’t funny, none of it was, not the casual cunt grabs or the crude reenactments or the five foot eight Caucasian males with medium builds and hands hungry for compensation (and do they ever feel satiated?), and ten years later, after all the performative laughter and the private heart, lung, and mind-wringing, you hate that you now find cool calm in the mutual woe of it all when you talk to other women who’ve had the same or similar Terrible Somethings happen to them, that you can say me too and find relief that you can add your pound of flesh to the scale in a way that carries weight, that anoints you with the voice of a main character instead of a supporting one; yet still you wonder if your casual cunt grab in that dark alley was too trivial in the grand line of Terrible Somethings to give it much swinging power—even though that man who you had never seen before that moment (and will now never forget) was the first man to touch you down there, in that place that once belonged only to you, and even though you were too ashamed to report your pussy crime and have it memorialized in an email and too ashamed to leave your room for two days after because you’d been drunk you’d been alone you’d been chosen in the same way you’d chosen that dark path to walk down because it was the shortest way home how could you be so goddamn stupid jesusfuckingchrist who are you to say you’ve suffered when you used to laugh in a former theater kid way (peas and carrots peas and carrots) at the very thing that happened to you, the thing that you were once too ashamed to name you now decree loudly, so loudly (in solidarity!) that you might as well engrave it on your Instagram bio, your acknowledgements page, your tombstone—but no, don’t be dramatic, darling, no really, please calm down: your Terrible Something doesn’t warrant the ink or the elbow grease or the MLA formatting; we’ve already laughed it into something as thinly drawn as a morning-after email, so delete it or perform it or forward it to all your friends out of fear you’ll die if you don’t—whatever you choose to do, we’re all in on the joke.  Brenna McPeek is a writer and editor based in Los Angeles. She has her MFA in Fiction from Columbia University and is the co-founder and editor-in-chief of Fatal Flaw. Her work has been published in Grain, Story, Harvard Review, Necessary Fiction, and other publications. Jes CC You Held My Hand, But Had Nowhere to Take Me Black and white faces, green eyes and my face cupped in the palm of your hand. Trust is a four letter word handcuffed to the bed. We can’t find the key so we dismantle the bed instead. There’s a glass of water left on the dresser, I haven’t awoken thirsty in months. I used to dream of waterfalls, fountains cascading around my bare feet. But now, hiding between your sweaty shoulder blades, I dream of nothing at all. Copper pennies and salted tears, the stain of last night’s wine on my teeth, I tuck them in the broken drawer on the right between the silky nothings you never tempt me to wear. Snorting salt and crushing crystal, the promise of sweet illusive gardens and emerald palaces drowning in your eye. I’m only free when far from home, and so I’m always running. You held my hand, but had nowhere to take me, so eventually we both let go. For months I ached with the taught promise of lovers circling each other like tigers, amber eyes locked, limbs ready to pounce. But every night we slept beneath heavy sheets, rarely unfolding to desire. I wanted you to know me deeper than skin. Once I skipped across a rusty bridge and saw pieces of mars in the sidewalk. I felt the moon in my wings and forgot I couldn’t fly. There was a magic in me. I wanted it back, if only for an instant. I stopped eating, sleeping. I lost track of the pills because the stars were blotting out the days. My skin dissolved. Sunbeams stung like jellyfish. The sound of your thoughts hurt my ears. I felt everything, with such intensity. Reality became pliable, a dream for me to shape any way I wanted. Everyone else moved slow as insects in molasses. I felt sorry for them. I sprinted down the middle of the road, daring traffic to stop for me. I needed to tug my body loose. I needed as far away from this life as possible. Trying to outrun a manic episode is like trying to outrun an eclipse. Eventually blackness swallows everything. Oh, but those moments of staring straight at the sun! Silver wrists and asphalt skies, the sinking feeling of staring up at the clouds when my head is spinning with too much me. I couldn’t remember how the streets went together, but I knew it had something to do with the mesh in my veins. The entire world was suspended in my arteries, kisses were giant pink planets, I spun at the core of it all. You looked so tired and sad. Two weeks I sat inside the mirror, watching myself on the other side. Flat blue rhythm world, vibrating at my fingertips. Little salt and sugar packets fascinated me, I was tempted to comb my hair with a fork. Cameras never left my face, I felt safe and protected. And then like thread through a needle, they pulled me through into someone else. Handcuffs rattling in the corner, and our lives are thrown on the floor. You step over me like something empty, I’ve left you unfulfilled. I tried to show you it would be like this. Wait for you to wipe away the dreams caught in my eye. I dig through piles of dirty laundry, hunting for those orange afternoons, pigtails and warm sinks of soap and you hungry mauling tender. Purple cave evenings, heavy breathing. Your kisses between my toes in the bathtub. I try to believe in something beautiful. “Get your head out of the clouds” you say. No, see, I’d rather not. You’ve turned me into something very ugly, and I don’t like your face anymore. You hold the door for me as I leave. In reality, I don’t look back. But, under the cover of dreams, I always do. I still sleep on the edge of the bed, and imagine you undressing me the way you did the first time, like the moon stripping the shore. Bare. But I always walk away. Sometimes I wake in the middle of the night, one hand clasped within the other, and I realize there are bridges I was meant to cross alone.  “I wasn't the kind of person who was afraid to show her scars. I saw beauty and strength in survival. Now I see survival, strength, beauty. And scars.” Carella is a writer and digital artist, published in numerous literary journals including Columbia Journal, Chestnut Review and Crannóg. Her writing was recently nominated for a Pushcart Prize, and she is a 2023 Door is a Jar Writing Award Winner. Her art has appeared on the covers of Glassworks Magazine, Nightingale and Sparrow, Colors: The Magazine, Frost Meadow Review and Straylight Magazine. instagram.com/catalogue.of.dreams / twitter.com/catalogofdream 3/31/2024 The Barr by Cole W. Williams Danielle Henry CC The Barr The ex-marine sent me two photos from night one. One of the boar on the ground of sand and seashells. One of the boar strung-up next to him—wider than he was just as tall. Lifeless. The Man said #250, maybe #300, this got way out of control the Man said. The night he died she was gone on a trip to Cali, working at an oil refinery—a strange opportunity for quick money. I was alone in bed at night in the dark as the smoke alarm went through a series of malfunctions. The strobe lights circled the room, the siren leapt to life; the sound and light made arrays of never-ending. Covering my ears, I looked at it and said Hey. The ex-marine called it a Barr: a hog captured, castrated and clipped in the ear. This hog was a roaming, raging testosterone. Transformation, eat be eaten. Now it would be a roaming raging storage of calories. The eat machine. Our coconuts. Our mangoes. Our livelihood. We would have nothing to sell. The year before I left her, I said, in a year I am gunna to leave you unless you x, y, z: x = invite the kid’s dad in y = less drinking/benders z = something about mental wellness I had my own work to do. Every New Year’s I was circling the drain of a sticky tar grief: the anniversary of his, my high school boyfriend’s suicide. A Barr is a live creature created with intention. An intelligent design. Someone had set the chaos eater free. In its orbit were boarlets; new generations of eaters…12…13…independents, following the Barr to our freshwater food forest. The Barr had been left for years to fend for itself, to steal, to break, to root-up the foundations of the farm meticulously placed over generations to be in synchronicity with the sun and production. The sun-leaf-fruit cycle was interrupted by a force which would take everything and had, year-after-year. She used to say, I don’t want to hear his name. Don’t say it out loud. Perform it: Happiness. Don’t show you loved him. Get out with your pain. Take him with you. Hold in quagmires. Oceans. I would take him, the pain, into the car to shed layers of oil-well darkness from my body. Then I would enter the home and pretend to housewife. At the gun and ammo store the clerk behind the counter excused the dripping water from the ceiling, asked what I needed. I told him a rifle. I held the bolt-action Winchester. I held a thirty-aught, and then a semi-auto AK-15 223. It was my farm. It was my problem. I imagined myself as a person who held a rifle cavalier--Oh this? By the end of the visit, I was handed a card with the name of an Ex- Marine that could take care of me. Are we open to possession by the demons of others? He killed himself on her birthday, New Years—some would call this a coincidence. There were deep rivets in the gullies of the groves. New signs of rutting sandworms from outer space. Coconuts shucked and broken open like sunflower seeds. Trails running from land into the darkness of the sausage tree. An acrid aroma. We were beginning to grow concern as the signs of infestation worsened. How long until we are taken over? How long until others notice? Some work to erase the names of others. Some enter a gladiator arena to battle. I said enough. I said peace and she turned away. My first few weeks on the farm I was alone. The dirt was old. Graying. And the trees were destroyed by a storm. I wasn’t looking in the right places. They were under. Hidden. I didn’t even know they existed yet/what they were or the damage they could do. I was naïve. A state that leaves me open to damage. She laughed. She drank and I began to erase myself from her life, crying-crying, scared of what she would do, knowing it would be bad for me. I returned a dish I once broke. A pillow I once stole. A home I once shared. I told her I was leaving. She laughed. She drank. I walked out on my life on New Year’s Day: He asked do I want to eat or be eaten, he tipped me over and leaked the infestations from my ears, reduced me to my shadows, he said this got way out of control, somehow I saw myself—everything. I thanked him and began to wonder about synchronicity.  Cole W. Williams is a poet, essayist, and hybrid writer. Williams recently won the Under Review's annual chapbook contest for "The Pump" and was recognized by The Florida Review's Humboldt Prize for the poem "Sunset." Bottlecap Press will be releasing the chapbook "Dear Annette," in 2023. Williams attended the 2022 Bread Loaf Environmental Writers’ Conference for poetry. Christine Stoddard Interview with Sally Jane Brown • Feb. 21, 2024 In this exclusive interview, Christine Stoddard invites us into her latest exhibition, "A Forest of Ancestral Dreams" (forthcoming with Baldwin Public Library in Baldwin, New York), where paintings and sculptures converge to weave tales of heritage, identity, and imagination. With a background as rich and diverse as her artwork, Christine shares insights into her artistic process, inspirations, and the profound connections between place, culture, and creativity. Your exhibit includes a range of media - mixed, painting, jewelry - tell me about your artistic process and why different media lends itself to your intent. The exhibition, “A Forest of Ancestral Dreams,” itself includes paintings and small sculptures. The paintings are acrylic or watercolor-based and incorporate other media: glass, paper pulp, pen, pencil, beads. There is one canvas depicting a large cactus, which has an oil paint base. I did not paint the textural base, which largely cannot see because I have covered it in acrylic, but you can see its topography. That is the only “oil painting” in the show, though it's hardly a true oil painting. The show also has a narrow glass display case with paper-based and glass sculptures: a puppet, a shadow box, an altered book, and a glass bowl. I was raised to reuse and recycle and appreciate literacy, history, and craftsmanship. My mother is from El Salvador, which has a strong handicraft tradition, especially paper goods and ceramics. Her sensibilities are influenced by mestizo culture, the blending of Indigenous Mayan heritage and Spanish colonialism. My father is American, a New York hippie of Northern English and Scottish descent. Both witnessed El Salvador's civil war firsthand and are pacifists and nature lovers. They are very tactile people, which explains my adoration of texture and materials. My siblings and I all took to drawing at an early age and made crafts with our mother at home. She often read storybooks to us and carefully pointed out the illustrations. She was never one to rush to the next page. Under her tutelage, the library was a weekly destination; there were even periods when she took us there everyday. Our father, a director of photography for news and documentaries, taught us about close looking, composition, and the magic of lighting. He was fascinated by politics and comparative religion, the latter of which has truly inspired me throughout my life. As a family, we took advantage of Washington, D.C.'s many free museums, plays, concerts, and festivals. I create in varied media in large part because I have been exposed to many media, but also because I feel free and motivated to do so. I am claiming my right to do so as a woman artist. QBG was also kind enough to invite me to sell work in the gift shop. I have my poetry/fiction book Desert Fox by the Sea, the Quail Bell Magazine anthology Lunar Phoenix, Blu-Rays of my feature film Sirena's Gallery (Summer Hill Entertainment), jewelry, tiny paintings, and sculptures small enough to fit on a home tabletop or bookshelf. Selling in a cultural institution gift shop is a dream I've had since I was a kid! So check that off the bucket list. I've had publishers arrange for my books to be sold in museum gift shops before, mainly my non-fiction titles Hispanic & Latino Heritage in Virginia and Images of America: Richmond Cemeteries. And that was super-cool. But this feels like a leveling up in terms of accomplishment. It is the first time I've had a gift shop represent my work across media for long-term, not just a one-day event. I really had the chance to curate what I wanted to make available to the public at affordable prices. Making my work accessible is important to me, though it is tough to do being an artist in New York City. With the cost of living being so high here, we have many costs to recoup. Fortunately, I have cultivated relationships that allow me to reduce some of my costs, in some cases getting resources for free. Two places that have been incredibly supportive in my journey as a working artist are Materials for the Arts in Long Island City and UrbanGlass in Fort Greene. Your statement relays some different place-related inspirations - your mother's Salvadorian ancestry + your father's Scottish - coupled with your upbringing in Virginia and current home of NY. How do these places, backgrounds, environments, impact your work and come through in the visuals? I don't think it's possible to separate yourself from the earth. It's also not possible to separate yourself from history. From a young age, I was made aware that I was the daughter of transplants. Though I have lived experience in Virginia, I have no roots there. I was the first in my family born and raised there. It was my home without being my ancestral home. There is a loneliness and a thrill that comes with that. A blank slate presents opportunity, yet the feeling of rootlessness can be quite unsettling. I have many memories of my mother getting made fun of for being an immigrant. Even my father was left out for not relating to the UVA/Virginia Tech rivalry or any number of things that excluded him from being a “Washingtonian” or “Virginian.” New York City attracted me as an arts and entertainment capital and a city full of immigrants. Of course, it is no utopia. Everywhere I have lived, I have tried to do as my parents raised me to do: look closely, notice the plants and animals, marvel at moments in nature. As important as it is to observe nuances, there is more that binds us than does not. I'm fascinated by borders, collisions, and overlaps. I've been fortunate to travel a lot in my life and plan to do much more. The more places you've lived and traveled and the more cultures inform your life, the more connections you make between peoples and histories. Like, I cannot help but see connections between the American Civil War and El Salvador's Civil War. Or the connections between the Scotland-England border and the U.S.-Mexico border. I think it's wonderful to be layered, to have many places and things shape you. It is also complex and not without its challenges. Something can be two things at once. Much of life is a contradiction and a conundrum. That does not make it any less beautiful. You have a mystical, maybe, surreal, approach to your work - with depictions of ghosts and skulls to animals, women and maybe religious figures or goddesses? I get some real Remedias Varo and Leonora Carrington vibes. Tell me about what stories you're telling, and is your work inspired by other artists before/around you such as these? First of all, I'm flattered by those comparisons. Because they are still images, paintings do not always have the beginning, middle, and end that we associate with narrative storytelling. But other elements of storytelling, such as character, conflict, and tension can be apparent, or at least discernible, in a still image. I like that paintings often invite you to ask what is the beginning of this story? The middle? The end? And where does this image fit into the story? Is it exposition? Rising action? A conclusion? I take inspiration from Catholic symbolism, Mayan motifs, Southern Gothic, British folklore and fairytales, Latin American Magical Realism, and cycles in biology and ecology. Again, I see more connections than I do hard-line boundaries. In 8th grade, I took a geography class that set the tone for the rest of my life. School was always a refuge for me, but I remember that year being hard in particular. My teacher, Ms. Holland, sparked my curiosity about the world and made me appreciate my place in it, which brought me a lot of joy. I loved making maps and dioramas for her class, listening to music from other cultures, and trying food from seemingly everywhere. Land shapes us in so many ways and we as humans shape it, too. This is a story for my art but also for all of humanity. In an early MFA project, I made a video about how, at that time at least, much of my mother's country of origin, El Salvador, was not viewable on Google Maps. During that period, I was thinking a lot about what makes something knowable vs. unknowable, real vs. unreal. I still do. I gravitate toward artists with the same concern and who also have rich aesthetic styles. I tend to prefer maximalism and vibrancy and don't usually go for pure abstraction. The list is always growing and changing, but some of my favorite painters include Frida Kahlo, Tamara de Lempicka, and Faith Ringgold. I know you are also a performer, writer, even comedian sometimes. How does this all come into play with your visual work? I want my visual art to invite the view into stories and worlds, and also invite them to play. Aiming for a playful quality in my work is something I do across media. I believe in using humor, levity, and charm to bring about smiles, laughter, and dreaming. Art doesn't always have to be super-serious, just as life should have room for fun, comedy, and imagination. While I cultivate a strong work ethic, I also cultivate a strong play ethic. Right now I am studying Oral History as a Master's student at Columbia University. It's a program about documenting and translating memory and personal narratives. Largely, oral history as a field is audio-driven, with a tradition of recorded interviews that may or may not be transcribed and published as text. The recorded interviews often go into an archive at a museum or library that isn't necessarily accessible to the general public. In more recent years, the field has become more visual. You will find more video interviews and overlap with documentary film. You will find drawing and painting more commonplace in the field, too. To me, this is a boon. I'm not a purist. I have found many performers also make visual art. For many, it's a question of what they are trying to “brand” or “market” when it comes to one medium taking priority. I prefer to put it all out there, at least when I'm half-satisfied with it. I'm a multi-hyphenate and I'm not going to let a marketing consultant shame me into hiding that reality.  What has this show at the Queens Botanical Center meant to you - what has been the response to the work, is it what you hoped? This is my first major solo exhibition in New York City. It is also my first true painting show. I have had two other significant solo exhibitions during my time here: my culminating show as the premiere artist-in-residence at Lenox Hill Neighborhood House (December 2018/January 2019) and MFA show at The City College of New York (April-June 2019). I had built up a lot of momentum for my art during my MFA and then the pandemic hit. In 2020/2021, I made my arthouse feature film Sirena's Gallery through the 1708 Gallery Space Residency in Richmond, VA. The film included my paintings and tapped into my visual art in that way. The film itself was rather experimental, too, so it definitely had an art-making, almost video art approach to it. In the few months after my MFA graduation, I had some residencies and group shows that brought my work to new audiences, including a group show at the Queens Botanical Garden. This was with AnkhLave Arts Alliance and was curated by Dario Mohr. That show gave me the confidence to pitch to QBG as a solo artist in 2022. My outdoor installation that was a part of the group show was especially popular and got specific mention in reviews. I was especially touched by one detailed review published by New York Latin Culture Magazine. Despite doing some painting during my MFA, I didn't show straight paintings in either of the 2018/2019 solo shows. Both were more photo and sculpture-based, with some drawing and painting integrated into the work. There were three experiences in 2019 that encouraged me to give painting a more serious go. They all took place around the same time, after I had already prepared the work for my MFA show. One was an artist residency at public schools through Lehman College Art Gallery. I was mural-making and teaching watercolor workshops to middle school students in the Bronx and Brooklyn. Suddenly I was watching YouTube tutorials and looking at art instruction books in ways I hadn't done since I was a kid. The other was a ceramic independent study with Sylvia Netzer, who was on my MFA thesis committee. She recognized that I was doing a lot of drawing in clay and finding unusual ways to color work after taking it out of the kiln, not just doing traditional glazing. She was very surprised to learn that I didn't really see myself as a “drawer” or “painter.” She pushed me to do more drawing and painting, and I'm so happy I did. Pretty much right after I graduated from my MFA, I was hired to teach art workshops to adults with disabilities and that led to making murals in group homes. All of this painting felt like a second childhood and it made me very happy. By 2022, I decided I had body of cohesive painting work. I started submitting exhibition proposals and by late spring/early summer 2023, I found out the Queens Botanical Garden wanted me to have a show that opened at the end of the year. The show is scheduled to run through March 18, 2024, which means a nice long run of four months. It was and is a huge honor. The opening was well attended, mostly full of strangers, which was exactly what I wanted. I love being supported by friends, family, and long-time acquaintances and colleagues, but reaching new audiences expands the work's influence. The garden asked me to visit their after-school teen program, which teaches students about food justice in New York City. The students looked at my exhibition, discussed it with me, and made mixed media watercolors with me afterwards. Most of the work had botanical themes to it, which makes sense given the context. There has been some local press about the exhibition, most notably a feature story in the Queens Chronicle. One of my favorite responses to the exhibition actually occurred in person. An elderly Chinese couple pointed at the work and gave me very enthusiastic smiles and nods. Another favorite happened with an Arab mother and adult son. The son, who spoke English, came to me and said that he and his mother liked my art very much. He then pointed at his mother's favorite painting and asked me to tell him about it, so I did. He went to his mother, who stood a few feet apart from us, and interpreted what I said. She smiled at me after he finished explaining. In both of these instances, I knew that my art had transcended oral and written language, which was tremendously gratifying. What are you working on now / what's next? I am working on my films Belladonna Magic and Her Garden, my TV talk show Badass Lady-Folk, and my live/digital performances of Art Bitch, Queen Jaguar, and other characters, as well as standup comedy. I'm also co-hosting the new comedy TV show Don't Mind If I Don't with Aaron Gold. Belladonna Magic is a compilation of video poems, one for each poem in my book Belladonna Magic: Spells in the Form of Poetry and Photography (Shanti Arts, 2019). The first public showing of these films will take place at FiveMyles Gallery in Brooklyn in February 2024. I will be editing the videos into one feature-length work by the end of this year. Her Garden is a feature-length experimental film I've been working on with collaborators Jacob M. Baron and Meagan J. Meehan. The story is about one woman's journey in understanding her mentally ill aunt; there are mermaids involved and a lot of sensuous imagery, especially of the urban post-apocalypse meets ocean vibes. It's been stuck in post-production limbo for a bit, but I'm not too concerned; I always have enough to keep myself occupied. I'm excited for this work to reach its audience sooner rather than later. Badass Lady-Folk is a talk show featuring conversations with incredible women and non-binary folks. Don't Mind If I Don't where fans and experts try to convince my grumpy boyfriend Aaron Gold to like the things he hates; I play the role of co-host and supportive, level-headed girlfriend. You can watch both shows on YouTube. *All artwork curtesy of the artist © Christine Stoddard Christine Stoddard is a multi-hyphenated artist and storyteller named one of Brooklyn Magazine’s Top 50 Most Fascinating People. She is known for her off-beat humor and poetic but playful experimental works spanning across media. Some notable examples include the critically-acclaimed stage play "Mi Abuela, Queen of Nightmares," the arthouse feature film Sirena’s Gallery (streaming on Amazon Prime, Tubi, etc.), the books Desert Fox by the Sea and Belladonna Magic, the performance acts Art Bitch and Queen Jaguar, and the culture publication Quail Bell Magazine. In December 2023, Stoddard took over the Brooklyn Downtown Star and Greenpoint Star as editor with her usual insatiable creativity. She loves penning her column "Believe the Hype" and "Forget Fairytales" comics for local readers. She hosts the feminist talk show "Badass Lady-Folk" and co-hosts the new comedy TV show "Don't Mind If I Don't" with Aaron Gold. You can find her work in Bustle, Cosmopolitan, Ms. Magazine, The Huffington Post, the Portland Review, Yes! Magazine, Native Peoples Magazine, Digital America, and elsewhere. Her work has appeared in productions, programs, and exhibitions by The Tank, the Queens Botanical Garden, the Gene Frankel Theatre, the Elisabet Ney Museum, the Players Theatre, the New York Transit Museum, the People's Improv Theater, the Poe Museum, and beyond. Currently, she is a book writer in the BMI Lehman Engel Musical Theatre Workshop and a Master's candidate at Columbia University. She is a graduate of The City College of New York and Virginia Commonwealth University. Find out more at WorldOfChristinestoddard.com Sally Brown is an artist, curator and writer currently based in Morgantown. Her artwork including drawing, painting and performance, explores womanhood, motherhood and the body. She has exhibited her work in spaces nationally and in the UK. She has won two awards for illustration for Intimates and Fools and Leaves of Absence, both with poetry by Laura Madeline Wiseman. She has participated in artist residencies in Tennessee, Pennsylvania and Buenos Aires. Her writing has been published in Hyperallergic, Women's Art Journal and Artslant, among others. She has curated group shows in Omaha, Nashville, Pittsburgh and Morgantown. She holds a Bachelor of Arts-Studio Art, a Master of Public Administration and Master of Arts- Art History and Feminist Theory. She is a former member of the College Art Association National Committee on Women in the Arts, edited the online journal Les Femmes Folles, and currently serves as Exhibits Coordinator for West Virginia University Libraries and associate art editor for Thimble Literary Magazine. Interview with Evelyn Berry, poet and author of Grief Slut By Kristy Snedden Grief Slut is Evelyn Berry’s debut poetry collection and what a debut! In these luscious pages she offers a poetic experience of the grief, pleasure, violence, and surprising tenderness of growing up queer in the American South. As a 1973 transplant to the South myself, I snapped up the chance to interview Evelyn. I invite you into her world and her written words. How long have you been writing and when did you become serious about your writing? I was serious about my writing from a young age. At age eleven, I decided to write a novel and vowed to publish it before age fifteen. It took an additional few years, but that reckless ambition served me well as a developing writer. Rather than worry too much about whether what I wrote was good or not, I cranked out six or seven full manuscripts before graduating high school. They were terrible, as all first novels were, but they gave me a kind of grip on narrative that I think serves me well now. I wish I could be so confident now as I was as a teenaged writer. In person, Evelyn tells me that her poetry is informed by South Carolina childhood scenes, including possums, dandelions, and boiled peanuts. Anyone southern who has paid attention will delight in her imagery when she writes in “Queer Ecology,” “young queers been fucking in the fields/ since the first sin first garden delight/ first adam’s apple taken in the mouth first seed spilled/ if they burry enough wild queers in the dirt// one’s sure to sprout in their backyard.” Wow! Evelyn, how often and how do you write? Under ideal conditions, I write every day, usually very early in the morning. I work best when I wake between five and six to write something before my anxiety rises out of bed to meddle the progress. For poetry, I like to write first drafts by hand. I prefer notebooks small enough to fit in my pocket. When I write fiction, I use one of two tools. The first is a word processor, the 2002 AlphaSmart Neo 2. When I’ve written more than two thousand words, I transfer the mess onto a computer for edits. Otherwise, I use a program on my computer called StimuWrite, which is a software developed by the horror writer Eve Harms, to help one write by mimicking the dopamine-processing of social media attention. I also often write in Wingdings font, so I don’t have to think too hard about what a mess I’m making. I do almost all of my revision in Google Docs. Writing, rewriting, erasing, rearranging, and playing with the text until it’s up to snuff. Evelyn talked with me about how she likes to find the “spaces where people can thrive” and when I ask her about writing her “swamp creature” poem and especially the stanza, “not every incandescence is beacon, some only a house burning/ or body/ lit from within,” she tells me that she was working “deep in the middle of nowhere.” Even in conversation, Evelyn spouts lines that sound like poetry. What are common traps for aspiring writers? In my opinion, too many writers struggle to share their work because they’re embarrassed it’s not up to the standards for which they hold themselves. They say, if only I get an English degree. If only I get an MFA. If only I take one more workshop, read one more craft book, wait one more year, then I’ll be ready to share my work with my peers. But sharing your work, either through publication or open mics, is a kind of magic. You’ll find that your words will connect, even if you don’t think they’re very good. Once the thing’s written and revised, the piece isn’t about you. The poem or short story lives in service of the reader who may find there a familiar hurt. Evelyn acknowledges that although poems “shift over time,” she still believes writers should take the risk and put their work out into the world. She is bubbly and engaging and it’s no stretch to imagine her on open mic night, engaging the crowd with her unique voice. What is your writing Kryptonite? I’m the self-flagellating type. I don’t believe anyone who tells me they like my work. I have to near-trick myself into writing anything. Have you ever gotten reader’s block? While I might spend periods of my life failing to write, I’m always reading. If I’m weary of literary novels, I spend my time reading manga series and comic books until I’m ready to tackle something heftier. What creatives have helped shape your mind and your work? Much of my thinking around art and the role of the artist comes from creatives like Keith Haring, Viet Thanh Nguyen, Annie Dillard, Toni Morrison, Dorothy Allison, David Wojnarowicz, Dieter Roth, Audre Lorde, and John Waters. If you could tell your younger writing self anything, what would it be? was flailing and writing bad novels as a young writer, but I don’t think I would have it any other way. I am happy to have failed so spectacularly so young so many times or else I wouldn’t have learned what I needed to learn. If I could go back in time to talk to a young version of myself, I’d probably not spend any time talking about writing at all. I’d be trying to convince me to try estrogen. Many of Evelyn’s poems reference the Southern LGBTQ landscape. I love how she peppers our conversation with references to her own identity journey and her poetry doesn’t shy away from difficult, even harrowing historical events, as in “controlled burn,” a poem that refers to a series of fires, including an accidental fire at Ghost Ship in Oakland, California in 2016, an arson attack at The Upstairs Lounge in New Orleans, Louisiana in 1973, and an arson attack that killed two gay men in their apartment in Dallas, Texas in 2011. I’m always interested in a writer’s “writing process.” What can you tell us about yours? I usually start by writing a long list of words that share some kind of sonic relation– rhymes, near rhymes, assonance, alliteration. Then I try to make sense of that sound, see what sounds good with one another and wait for my subconscious to make meaning from the song. I take revision very seriously, so those first drafts don’t survive. They’re usually disassembled, stripped for parts, and cannibalized. Evelyn shows us her careful attention to sonic relationships in “lotus eater,” with the lines “…I once mistook/ meth for molly,/ but swallowed/ still, then stripped/ out of my skin.// bite into the apple,/ spit out a razor,/ spit out a razed orchard.” I will be playing with this method myself! What period of your life do you find you write about most often? I’ve spent most of my writing life focused on childhood and young adulthood. I haven’t written much about my life now, as a thirty-year-old trans woman living what is to me a boring, domestic life and to others the most radical life path they can imagine. As I begin to write poems for my next collection, I’m turning away from memories of youth and looking toward ideas of trans motherhood. Most all, I feel like I’m writing into the future these days. What did you edit out of this book? The first version of the manuscript, completed in 2017, contained many more poems about addiction, as I was in the process of sobering up after years being addicted to opiates. Many of them were nonsensical, silly, and too romantic about being fucked up. I cut many of those from the manuscript during the years of revision. Once the book was accepted, we whittled the poems down a bit by removing some of those that didn’t serve the book as a whole. Many of those poems were love poems or poems that didn’t have anything to do with the themes in which I was most interested. One of these themes is grief. Many of Evelyn’s poems refer to the death of a close friend who killed himself in 2020. As a fellow human left alive when someone I loved killed himself, I especially resonated with, “ritual is a just another name for the habits grief carves from a mourner’s tongue,” and “the only thing I know of god is shard-scattered in the river,// discarded jug we used to carry water home./ if I could, I swear, I would collect every piece of you.” Do you have any secrets in this book? …This book is nothing but secrets. It’s actually quite freeing to have written and published this book chock full of my worst shames. I put them in a book and don’t feel ashamed about those feelings or memories anymore. That shame has been alchemized into poems, that pain shared. What is the most difficult part of your artistic process? I’m impatient about my work, but I think it’s important to let drafts sit. Waiting is essential to the process, but it’s dreadful to wait. Meanwhile, of course, I’m caught up in the drama of wanting to publish, market, and share the final product. During that time, when I’m letting a book or poem sit by itself, I’m processing how to revise it in my mind. The secret’s not to lift the lid too early. You’ve got to let it sit for a while, simmering and stewing in flavor. Evelyn talked to me about how the “Grief Slut” changed from when she wrote the earliest poem in 2017 and the final poems about two months after submitting the manuscript to the publisher. Over five years, I wrote, rewrote, revised, reimagined, rearranged, and compiled the poems in Grief Slut. I wanted, most of all, to write a book with the best possible poems I could write at the time. I wanted to write specifically about grief, the personal and public archive, queer history, the transformative self, gender transition, and my experience as a queer person growing up in rural South Carolina. It wasn’t until 2021 when the book started to look similar to what was published in the final version. I think of “Grief Slut” as a book about becoming, a book that necessarily had to undergo radical changes as I went through one of the most painful, transformative periods of my life. When we talked about the poem, “on the question, “wait, can trans women reclaim the word faggot?” Evelyn said that the meaning changed as she began transitioning in 2021 and that the poem is based on a true story. I won’t say more than that – people will have to read this poem for themselves! What inspired you to start writing poetry? I mistakenly believed poetry was easy to write. Once, when I was seventeen, a local competition paid seventy-five dollars for placing third. I thought to myself, if only I can crank out a poem once a day for the rest of my life, I could make seventy-five dollars a day. When I realized, years later, how impossible the entire endeavor was, it was too late. I’d read and written too much poetry. I’d been changed. Who are some of your favorite poets? Why do you like their work? Contemporary poets who have shaped my sensibilities include Paige Lewis, Sam Sax, Chen Chen, Danez Smith, Rachel Zucker, Ocean Vuong, torrin a. greathouse, Sam Herschel Wein, Franny Choi, Kaveh Akbar, and Shira Erlichman. I’m attracted to writers who risk something in their work, especially confessional poets who let us into the painful parts of their lives. There’s something thrilling and revelatory about someone allowing themselves to be known so plainly. Evelyn clearly accomplishes this with her poetry. I found so much emotionally resonant material in “Grief Slut.” She has written many lines that will stay with me, including these from “tres(passing),” “i decide to stay another year,/ to carve a home, to hum the trans body/ into a song that belongs here.” Is there a poem in this collection that is your favorite? The poem “Praise Song in Lieu of Obituary,” which is the first poem in GRIEF SLUT, is incredibly important to me. It is a love letter to a past version of myself. Do you have any funny stories or anecdotes about your experiences as a poet? I came of age in the poetry world as a performer before I learned much about craft. But that means I learned other important lessons, like keeping a crowd’s attention, dealing with drunk hecklers at a bar, and performing my heart out to a mostly empty room. I’ll never forget one show where I featured at an open mic at a pizza shop. The cook that night didn’t like poetry, I guess, because he cranked up the music in the kitchen loud and started banging pots together throughout my set. It sparked a fight between the poets and the pizza-makers, and I think my feature there ended the series forever. So, these days if anyone is apologetic about a small crowd or a long drive to a show, I wave it away. I’ve performed under much worse conditions and survived to tell the tale. Such energy and courage! What would be your number one piece of advice for someone who wants to start writing poetry but doesn’t know where to begin? Read poetry. Read widely and deeply. Read work outside your comfort zone. Take that reading seriously. Do so with a pen and paper on hand. Try to notice what the poet does and how. What theme comes up frequently in your poems? Queer history, the fat/trans body, southern-ness, rurality, grief. Evelyn infuses the rural south into her work in a way that creeps up and covers the reader. Even if you’ve never lived in the south, you will have the southern experience when you read her collection. How do you know when a poem is finished? I’m notoriously bad about revising poems for years on end, even after they’ve been published. I suppose I’ll stop now that the poems have found their way into a full-length book. Otherwise, I believe poems can continue to be revised ad infinitum. As we finish this interview, I will quote from one more poem I loved that speaks to Evelyn’s authenticity and vulnerability as a writer – from “yes i’ve seen the future & i promise i’m still alive.” Evelyn writes, “i am translated most simply/ as constellation cluster of star/ with a name/ i’ve chosen myself/ i ache/ i break open/ & like water abandon form/ i carve/ my feminine name the same way/ a river fissures/ rock into ravine slow and deliberate:// oh! Evelyn, where have we been?” Evelyn Berry’s book, “Greif Slut” was published by Sundress Publications in December 2023. To learn more about Evelyn, find her at: EvelynBerryWriter, Instagram: EvelynBerryWriter, TikTok: EvelynBerryWriter, Youtube: EvelynBerryWriter, and Twitter: Evie_Writer. 3/31/2024 Grief; Unpeopled Spaces by Irene Gentle Danielle Henry CC Grief; Unpeopled Spaces I read up on grief long before anyone close to me died. I wanted to prepare. Then they died and I was not prepared. I was lucky to live quite a while before death came knocking. When it did, it came in packs. My father-in-law, who I was close to. My dog. My brother. My mother. My job. But this is mostly about my brother and mother. All my life I loved my brother unreasonably. We left home at about the same time, me the youngest at 17, my sister at 22 and Jim in the middle. By the time he died we had not lived under the same roof for decades. He was complicated even as a child, shouldering an old-fashioned man of the house role before puberty, an awkward fit for a scrawny, freckled kid but he had my mother’s unwavering devotion and glowing charisma. People of all ages were drawn to him, bestowing in him the hubris of someone widely adored without trying. The only person I’m sure he loved is his son, who arrived many years later. To this day I don’t know if he loved me back. Nor do I care. With or without love he took what he saw as his responsibilities seriously and I was among them. A series of knocks kicked his hubris down. He became ill. His death was neither operatically prolonged nor sudden. There was indication of illness, six weeks in the hospital, then death. I spent those weeks with him, watching him want to live for his son. His valour rocked even his hospital doctor. It ennobled him, and awed and brutalized me. He died and grief began. It’s idiotic to compare the love of people and a dog but my dog is one of the few things I also loved unreasonably and without need for reciprocity. She was with us almost 18 years. As she declined, unable to walk, skin and bones, a slip of herself, I pre-mourned. She had a heroic will, a stubbornness of self even as her body melted. I grieved alongside her while she diminished. I feel the loss of her to this day. Her absence is like an extra part of me. An addition, not a subtraction. I could not pre-grieve my brother. He did not intend to die when he entered that hospital and I did not intend to lose him. Hours of quiet watchfulness, observing every breath or sign of discomfort or want, laced with adrenaline. There was sleep but no rest. Quiet but no calm. Six weeks of the eternal moment before the finger pulls the trigger. Adrenaline with no outlet erodes you from inside. It was just the two of us when he died. In my mind it felt like the depth of night but in fact it was 10:30 p.m. My husband picked me up from the hospital where they’d placed a white dove on his door, their signal the patient is no more. We stopped for takeout before returning to the room we’d rented for the last months to be by my brother’s side. This the first of a new landscape, eating when he is dead. Adrenaline that wears off leaves an emptiness. To sleep I picture myself fading into a black river, thick and viscous. I carry the image with me through the day. My only comfort is submerging into this thick black river. It works for a bit until the river wants me out; I can lower onto it but not inside it. So I float along it instead like an Ophelia. I dream of obsidian without knowing what obsidian in. When I learn it’s smooth, glossy blackness is cooled lava I picture melting into a wall of it, becoming invisible. Grief is different for everyone. Some want the world to stop but I wanted it to flow on without me. Let me melt into darkness, alive but unbidden, unneeded, unseen, unbothered, untethered, unavailable. Let me watch from the shadow with my eyes closed. Let me be still while time moves. Eventually that ejects me too. Until it happened I did not realize the physicality of grief. It manifests in me like an illness, ever-present nausea, a swallower of breath. Movement is effort, any movement. But the helpful guides say it is necessary so I move. I walk, I do yoga, light weights. I meditate. I spend hours trying not to get worse. There is so much work to be at this level of nonfunction. My mother loved many in her life, her parents, her brother, her children. Her former husband (our father), banded with hurt even decades after the divorce. But mostly she loved her son. They were a unit that could not be severed. In the months between his death and her turn in the hospital he died in, we grew closer. The relationship between she and Jim an invisible wall the rest of us couldn’t breach and because they had each other, we didn’t try too hard. With his physical absence the wall came down and small communications flowed, emails of beautiful things, photos of flowers or birds or trees taken on those daily walks to stay in place. She was an immensely practical person with a whimsy, a poetry, a love of joy and things that shimmer and glint in the light. I found in her someone I could share those things with. It was a walk through grief but also a walk closer to each other. From the window of her crowded hospital room less than five months later she can see the ward where her son lived his last weeks. She tells nurses and doctors about it. My son was here too. Her illness, a small stroke, reveals the surprise of a well-developed cancer. A naturally curious person with an intellect and interest that in a different time would have led to a different life made her view her condition with a kind of surprised awe. She chose no treatment including food, a route that should have seen her wither in a matter of double-digit days. But she died after one. Grief doubled. Grief complicated, they call it. A complicated grief. The helpful guides say to keep the deaths separated, to mourn them individually. But it can be hard to untwine. The nausea, barely diminished in those five months, slams back. The heaviness. The impossibility of movement. It’s approaching a year now since my mother died, almost 18 months since my brother did. I grieve them entwined and separately. I miss her every day, I want to tell her something I saw or did or talk to her of baseball or current events. My brother is less often but is disembowelling when present. Like a movie in which the character is thrust through the gut with a sword and when the blade is pulled out blood jets out. There is no softening it. When I don’t think of his death, the blade remains in me. When I do, it withdraws and blood tumbles like a river. Every grief is different. My dog’s absence is like an extra part of me. My brother’s is flesh hacked out of me, a void with no hope of closing, like a cartoon character with a big round hole where the cannon blew through. My mother’s absence is a shimmer of undelivered thoughts and messages, a conversation with no one at the other end. This may be why my readings on grief were futile, no grief is the same. There’s a loneliness even talking with my sister, her experience of our brother and mother is not the same as mine, her grief s as real and as different as those perceptions. Grief reveals contours you didn’t know existed. At a small but significant moment of my brother’s estate, by no means the end of this harrowing and repellant process in which the person dies again and again and again with each account to close, bill to pay, passport to destroy, I was overcome. Tears in the bank where his account was closed, on the street, down the sidewalks leading home. So this is sorrow, I thought. This is the difference between sorrow and sadness. I looked it up after and there is a difference, like between pond and ocean. I had known sadness but not sorrow. And now I do. Helpful guides suggest leaning on faith. Afterlife, reincarnation, the presence of ancestors, angels or god, I was willing to accept any of the possibilities most my life. But an openness to all, I learn, is a belief in none. Maybe they’re in heaven also means maybe there’s no heaven. Maybe they’ll come back in a different life means maybe they won’t. Maybe they’re a presence around us means maybe they’re not. I want to think of them happy somewhere. Of course I do. But I find no solace in what I don’t feel. There is no ritual or path to follow. That finality, I learn, is an agony. Living is an endless stream of chances to fix things, change things, have another go, make another start, see the sun, feel the breeze, hear the call of a cardinal, recover from that blunder, get over that slight, make up for that hurt. I yearn for my brother and mother to have the chance for mundane happiness, moments of warmth, love, even a good cup of coffee. If afterlives and reincarnation are man-made fantasies, this is why. It’s the redemptive necessity after a life of hardship to receive contentment, a life of worry to know ease. Grief is not just the loss of them but the loss for them. What they lose in not being able to try again. Grief jolts you with an electric awareness of the importance of being happy at the time when happiness is most out of reach. Helpful guides say you are changed by grief. You will never be who you were before. This in my experience is entirely true. It has changed me fundamentally. My fairly deep sense of self and belief in my core competency evaporated. Sometimes I still speak with authority or find myself taking charge like I used to but it’s muscle memory. The ache of a phantom limb. Words I used to live by, like truth, justice, good are like spilled jars. I don’t know what they mean. In this is opportunity, to redefine. If I don’t know anything anymore including myself, my job is to find out. I’ve written all my life. I’ve been a journalist and editor my entire career. But words dried up the first year of loss. They’ve returned but with a different purpose. The statue of justice, blindfolded with sword and scales, is tattooed on my arm. The words often used in the act of journalism are martial. Journalists are frontline. The pursuit of attention is a battlefield. News is breaking. Editing is cutting. Change happens when those in power have their back to the wall. The arena of journalism was my fight, my sword, for many years, and it’s impossible for me to think of it as anything but a battle. Journalism needs to evolve, and is, and so do I. Today my sword is put away, I think forever. I’m taking up the slower tools of planting and building. I won’t extract but will look for ways to add. I won’t appeal to the intellect but to our humanity, the one thing that may still pull us back from this brink. I lost faith not only in myself but also in the human mind, I’ve seen where that takes us. I hope to find some faith again in a common heart. I’m starting from nothing, but I’m starting. If there is a gift of grief I haven’t found it but through grief is a glimpse of the gift of life. In pure stubborn existence there is the chance to redo, reassess, reorder, retreat, regroup, restart. Another word for life is again. The sun rises again, you breathe again. Again is the burden and gift of living, unbearable, amazing.  Irene Gentle is a writer, editor and journalist based in Toronto, Canada. Former editor in chief of the Toronto Star, words of a different kind currently in The Eunoia Review, The Hooghly Review, Litro Magazine and JAKE. 3/31/2024 The Mink by Jana Harris Danielle Henry CC