|

5/27/2020 Between Wildfires by Camara FairweatherSiletzs Territory, Oregon, 1845 Adelaide stepped down from her horse and looked out across the open plains but couldn’t see anything more than dark outlines in the evening dusk. As she stood there, listening to the cicadas in the distance, a dry wind twisted dead leaves around her. The wildfire had died some days back. There were still embers trailing through the air, racing red and hot among the white ash. ‘Steady now,’ she said in a low voice, running a hand over her mustang’s rosewood mane, feeling the soft touch of the brushed hairs passing between her fingers, ‘I’ll be back before long. Be good for me until then, okay?’ She pushed her wide-brimmed hat back onto her head, gathered the reins, and with one last look to the horizon, set about tying her horse to the black remains of a tree. She wasn’t exactly a Christian woman, nor was she the God-fearing type, but as the embers flamed and sawed beneath the evening sky, she couldn’t help feeling as though she were staring at a scene from Revelations. She lifted her father’s double-barrelled shotgun from the leather saddlebag and turned it over in the half-light. She liked the way the gunstock rested in her arms. The weight of the wood. The cold touch of metal against her skin. Made her feel alive to the narrow truths of the world. About the only thing that did anymore. With a shallow breath, she broke the double barrel, chambered the 10-gauge rounds, and started down the trail. She moved slowly, staying close to the ground. A solitary figure against the dark and empty landscape. As she walked, she saw the carcasses of animals lying face down in the pale ash, smoke rising from their blood-black fur. The dry river bed had once been home to freshwater fish. As a young girl, she had seen them swimming in the clear current and watched as their small fins weaved between the white edges of the water. The wind-kissed banks were wet with honeysuckles and moss, sparkling in the low sun. It was there, among the deep green shade of the pines, that her father taught her to fire a shotgun. She remembered waiting, perched in the thickets, her father breathing over her shoulder, as she tracked a white-tailed deer between her cross hairs. She had moved instinctually – pulling the trigger in the space between heart beats – that short moment between breaths. The deer faltered and fell. She skinned the animal later that morning, starting at the back legs, cutting along the tendons with the sharp edge of a knife. The muscles had a lot of gristle. It had taken her some time to saw through. When she finished, her father had been so proud. Said she was a natural. He was dead now. Buried in an unmarked grave. Somewhere on the outskirts of Louisiana. She thought about her parents as she moved deeper into the ashen valley, following the set of tracks drawn across the trail. Her father had been a slave. Her mother a southern belle. They had met on the bayou and spent the short time they had together out on a wide gallery porch under deep overhangs. Her memories of them were sun-bleached and faded. She found it hard to recall their faces. They drifted away from her reach, lost in the wind, like a dusty and half-remembered photograph. After a while, the dead grass gave way to a small clearing out on the plains. A man growing into his later years was resting against the hard edge of a rock, warming his tired hands by a dying fire. Above him, hanging from the thin branch of a tree, was a lynched Native American man. His buckskin shirt ripped. His face paint scratched away. And the words ‘red-skin’ had been written across his body in blood. ‘Hey there, old-timer.’ ‘That’s far enough.’ The man said in a whiskey-soaked velvet, hammering his .44 caliber revolver. He had a hard face. Smelt of cigar smoke and rough-hewn wood. ‘Now, I’ve never really liked repeating myself so I’m just gonna say this one time. You come any closer and the next round I fire will be the last thing you see.’ ‘I know it’s been a while but I figured you’d recognise me.’ ‘And why’s that?’ ‘I’m a ghost from your past.’ She said, stepping forward into the firelight with her shotgun holstered, the sound of her spurs carrying on the wind. ‘Now, ain’t that something. You’re the little half-caste girl from Red River.’ ‘Yeah, well, not so little anymore.’ ‘You’re a long way from home.’ He took a drink from the barrel-aged whiskey in his left hand. Spilled some down his thick beard. ‘What you doing all the way out here?’ ‘Thought the shotgun trained on you might speak for itself.’ ‘That a threat?’ ‘More of a promise.’ She watched the old-timer’s hand tighten around his gun. ‘I’m thinking you probably don’t remember that night or the way the wind howled across the empty fields. But I remember, young as I was. Pillowed there between my mama’s arms. The cold turning my breath to steam. Sometimes I think about the stillness of those moments. The wild rabbits hanging on line, swaying softly above. So intimate and fleeting. Like the faintest whisper. Then I heard the sound of horses in the distance. Horses being ridden hard. The sound of their hooves cutting through the snow. The sound of riders dismounting. The sound of spurs outside the door. The voices of white men closing in. Heart pounding. Door not opening. Voices getting louder. Cursing outside. Mama telling me to be quiet. To hide under the bed. Daddy getting his shotgun. Kicking against the door. Wood splitting. Door breaking. Daddy being dragged out like a junk-yard dog. Mama screaming. The sound of a gun firing. Daddy’s body hitting the ground. Birds scattering. Mama crying. Tears falling. Hands trying to stop the blood. Another gunshot. Then no sound. No sound but the wind.’ She drifted away into silence, taking a quiet moment to breath. The fire between them had burned to coals. It’s warm light died before she spoke again, ‘I still remember the last thing you said before turning tail. Said there are two kinds of people in the South. The quick. And the dead.’ Her eyes narrowed. ‘You want to know which I am?’ The old-timer moved to fire his gun. He was a fast draw – but Adelaide moved faster – firing the revolver out of his hand. ‘That’s right.’ She said, staring down the smoking barrel. ‘Now, raise your hands. Nice and slow, okay, old-timer? No sudden movements.’ He raised his hands some reluctance. ‘All this for a cotton-picking nigger and a white bitch that couldn’t keep her legs shut.’ Adelaide back-ended him with the shotgun, bringing the blunt wood down across his face. Heard bone break as he staggered back – wounded – and kicking up dust. He smiled through bloody teeth. ‘Seems you got me at a disadvantage.’ ‘Don’t smile at me because I’ll rent the smile from your face.’ ‘I’ve never really given the words of women much credence, but I figure I’ll push my chips forward. I’ve been at this a long time. I know a killer when I see one. And you ain’t got the sand.’ She pressed the shotgun barrel to his neck. ‘Then you must not win a lot of poker games.’ She said, exhaling sharply, and there was a cruelty waiting behind the dark and ghostly reaches of her eyes. ‘Do you even regret any of the killings your gang of outlaws laid claim to?’ ‘No. I surely don’t.’ He said, spitting blood. ‘That’s funny. Because I don’t regret killing any of your outlaws.’ She watched his face turn cold. ‘You’re lying.’ ‘Shot and killed every last one of them back in Albany.’ ‘That’s a damn lie!’ ‘I think you already know it’s not.’ She said, pulling a six-shooter from her belt and letting it fall to the ground. He looked down at the blood-rusted metal. ‘That’s my boy’s gun.’ ‘Was.’ She corrected him. ‘That was your boy’s gun.’ He held the revolver in his shaking hands. ‘You’re a rattlesnake on the trigger, I’ll give you that,’ he muttered darkly, ‘but you’ve forgotten that the land beneath you is corpse white. And that ain’t fixing to change. Even if you bury me and salt the grave, there’s nowhere for you to run. This country is full of pitchfork and torches and as long as there are trees in the South, they’ll be lynching black bodies from the branches. They can talk about giving you niggers rights. It don’t matter. Those southern trees have deep roots. Roots that spread in the dark. Been there growing since way before you were born. And they’ll keep growing after you die.’ He looked then to have the Devil in his bearing. ‘You can try to run, rattlesnake, but you’ll be impaled on those roots. And the birds will pick you clean.’ She watched, through the pale and driftless smoke, as he aimed the revolver at her. His finger itched on the trigger but she knew that he would never fire. There was only so much fight in a man and he’d lost his. ‘You think I don’t see you for who you really are?’ She asked with a hollow inflection. ‘All these years, I used to think you were terrifying. I’d wake up in cold-sweats, thinking about the violence you laid at our door, but I was wrong. Because you’re not terrifying. In the end, you’re just so small. I don’t really give a damn if you think I’ve got sand. Your life ends now. You can say whatever you want. This cowgirl has heard it all before. All you can do is pray for a quick death, which you and I both know you ain’t gonna get.’ He opened his mouth to say something cold and callous, but she cut him down before he had the chance. She stood over him as he clawed at his throat, reloaded, and shot two more round into his flesh. He died then and there. Looking down at the ground, Adelaide saw her reflection for the first time that night and recognised that something had changed within her nature. As she walked over the blood, back to her horse, she watched the reflection of the darkening sky ripple beneath her. She didn’t know it then but there would be another wildfire in a few years. Summer after summer the sky would refuse to rain. The wildfire would cut through the plains, burning crops and trees and wiping away whole towns as though they were nothing more than tinder. Some people would burn alive. Others would suffocate from the inhalation of smoke. And many would run, leaving the lives they once knew behind forever. The wildfire would burn away all the cowboys hanging onto their fading way of life, as if they had never really existed, but Adelaide would remember.  Camara Fairweather (b. 1998) is a biracial writer, illustrator, and poet from the United Kingdom. He has worked for BBC Three and flagship programs such as Newsnight. He is currently studying at the University of East Anglia. 5/27/2020 Acablero by Susann Cokal soleir CC Acablero One, two, a dozen of them followed us. Slippers soft, feet shuffling. Eyes probing for the body beneath the baggy dress. “Hey, lady,” somebody hissed, “wanna sit on my face?” I didn’t look up to see who had said it. I kept going, following Mark and Heather, my fiancé and his boss, on my very own private tour of Acablero State Hospital. “… a population of almost twelve hundred men, Beth,” Heather was saying, “all of whom receive …” Heather was the hospital’s lead psychiatrist. She had her speech on autopilot as we walked down corridors and past office after office. All drab, all mottled with layers of graffiti now scoured and painted over. Mostly genitals, from what I could see, with emphasis on the male. “State Hospital” was a euphemism. This place was a warehouse for mentally challenged criminals and their infinitely worse cousins, the Sexually Violent Predators, whom the state of California was attempting to cure with antidepressants and talk therapy. The SVP’s came here when their prison sentences were up and they couldn’t satisfy parole boards. The disabled inmates might never get out; they didn’t understand crime as a concept, and the predators knocked out all their teeth and used them as drug mules and sex objects. Everyone was entitled to roam the halls; the doctors believed that the open-corridor policy helped them socialize in a normal way. They would learn to break free from their wounds and desires and old coping strategies, everything that made them want to hurt other people. They would change. “How ’bout I sit on your face instead?” “You doing okay, Beth?” Heather asked over her shoulder. She had that shrink-tic of saying a person’s name far too many times in order to create what Mark sometimes called into-me-see. Other than that, she was so small and pinched and frail-looking that I wondered what could ever have inspired her to take this job and whether the patients baited her with face sitting. I concluded that they must. Then wondered how she managed to counsel them when they did. I caught another murmur behind us: “Ohmigawd, ain’t we just too fancy to talk to!” Folded into myself, arms across my chest, I asked in a low voice, “Do they ever attack?” “Don’t whisper,” Mark told me. “It makes the men nervous.” “COME ON, LADY! SIT ON MY GODDAMN FUCKING FACE!” Heather said, “We’d love to get you started next week.” * * * I wasn’t the kind of girlfriend a man typically shows off to colleagues. I also wasn’t the kind that a man normally moves three hundred miles to be with. I was artsy but not an artist, large breasted but also potbellied, the “such a pretty face” kind, as Mark once said—and my face wasn’t all that pretty. People thought I’d got lucky. I thought so too for a long time. Mark was better-looking than I was, dark blond, with hazel eyes that he insisted were green. He had a goatee that I never told him I disliked. We’d met through a dating site that cast a wide net, and we had a long-distance relationship till he announced, just six months in, that he was ready to move down from Napa. He had already found a job, this job, at the state hospital. He wanted to live with me. I was so surprised that I said yes, though he didn’t really seem to need an answer. And so he arrived, with more boxes and stereo equipment than my little house could hold. Some of his stuff was still sitting in boxes. My cat, Pearl, liked to dig inside the open ones, and she left drifts of white fur on all of his things. Our world was very small. Though I believed Mark was generally well liked at work, he had made no friends in the area except me, and somehow that meant I couldn’t have friends either. I did have a promise ring, though, a silver Claddagh. Two hands holding one heart—it embarrassed me with its outright sentiment, made me feel guilty in ways I did not understand. I thought I’d seen Heather stare at it appraisingly. I was here now because Mark wanted me to lead a workshop to help the men write their life stories. He thought confronting their crimes would help them rehabilitate. Not the disabled ones; no one believed they were capable of change. Just the SVP’s. It would be a roomful of blue-uniformed predators and me, his future wife. Heather unclipped a key card from her belt. “Beth, this could be your classroom,” she said with a ta-da in her voice. I went inside first. It smelled of dirty socks and testicles and had no windows. I saw traces of an especially large penis glyph on the far wall, bleeding through a layer of beige paint; it was thrust between round globes too big to be balls, and I couldn’t decide if they were supposed to be breasts or buttocks. I would have liked to find this funny and to make jokes about it with Mark, but he wasn’t paying attention. He was frowning. He had turned on one in a row of grubby computers, and the screen image flickered unhealthily. The prisoners clustered like deer in the doorway. They didn’t follow us in, but they were curious. “These computers are only three years old, Beth,” Heather informed me. “We got grant money for them. They have the latest software updates too; we got another grant for that. No internet, though—unless you have a special code.” As if on cue, Mark looked up from his terminal and gave me a smile. Perhaps he thought that our online courtship would inspire a fondness for any computer now. “Can we use paper instead?” I asked Heather. And immediately regretted the question, because by asking I seemed to have made a commitment. “I mean, if I do teach the class,” I added lamely. “Oh sure.” But Heather’s pursed little mouth turned down at the ends. “You can have paper and pencils, Beth, if you count all the pencils at the end of the session and take them away. And make sure none of them are broken off and carried away. But it would be a shame not to use these computers—that’s another skill the men might need on the outside.” I didn’t like to think of “the men,” the predators, released into the world of prepubescent children and single mothers, middle-aged office workers and elderly widows. I liked even less to think of helping them get out. It seemed that, under Heather’s approach, the truth really would set them free. A Sexually Violent Paradox. * * * That night, Mark broke my jaw. I remember thinking, At last, here it is. Some part of me had been preparing. As his fist hit my face and my face hit the counter, there was only one why to ponder. Why tonight? Maybe my fear of ASH was exciting to him. Or he was mad because I hadn’t represented well in front of his boss. Or he’d realized I wasn’t pretty enough. Or he was frustrated with having moved so far to find not enough room for his things. I lay on the kitchen floor, trying not to breathe. Trying to move my jaw but not able to. Mark poked me with his toe. “You going to get up?” he asked. * * * “So what do you think?” he’d asked that afternoon, once we were buckled into the car and well on the winding road to Los Osos, where my little house perched in a sandy cul-de-sac. “What do I think …” I stalled. I hated talking in the car, especially about anything important, and most especially when Mark was driving. He was hard on a gearshift, but he liked to drive and I thought it wasn’t worth arguing over. I was learning how to make compromises. I had never lived with a man before. “I’m not sure,” I said honestly. He took a curve fast. “Don’t you want to make a difference?” I’d always found that phrase problematic. Many differences are for the worse. “I feel sick,” I said. “Could you go a little slower, please?” Mark took his foot off the gas for a second, then put it back down, making us lurch. He blew air noisily through his lips and scratched the back of his neck as if he’d been stung. “You’re always complaining about your job, Beth,” he said. “This is your chance to do something really meaningful.” There it was again, the psychologist’s tic, the into-me-see. Except Mark had it wrong. I liked my job. I was a grant writer and administrator for a community arts organization, mostly serving retirees who finally had the time to learn to paint with watercolors or make their own jewelry out of titanium. I didn’t know when Mark thought I’d been complaining; I loved the cheerful seniors trouping past my desk with their oversized tablets and baskets of brushes. I loved it when one of the teachers, the “real” artists, was out and I got to take over a class. But this was not the time to say so. Compromise, I told myself. Grassy yellow hills flashed by, dotted with purple splotches of sweetpea. We had reached ranch land. “I’ll keep thinking about it,” I said. “I don’t know if I can make it work with my schedule at the Center.” “Do the class on the weekends. Saturday afternoons.” “The AC has events on Saturdays.” “Not every Saturday.” “Often enough.” I realized with a jolt of fear that we were bickering—and then recognized the fear. It had grown out of an uneasiness that had developed since he’d moved in, as we’d found places to put his clothes and stereo and television but not his c.d.’s and Elvis memorabilia. As he slammed the lid on the washing machine after Pearl threw up a hairball on his quilt. As the dishes piled up and he threw away the salad I’d made for dinner, because dinner should always be hot food. “I could probably make some time,” I said. If I scheduled my class for Saturdays, was I supposed to go there alone while Mark stayed home? “I’ll talk to my boss.” Mark must have noticed that I wasn’t making any real promises. But he didn’t say anything more but just drove, still faster than I would have liked, until the smell of cows was overtaken by the tang of salt air and we were home. * * * Before the doctors at Grace Medical would let me go, I had to see a staff therapist. She sat me down in a room with comfortable chairs and asked if I feared for my safety. My jaw was wired shut and the rest of my face was so swollen that my left eye had closed. There was a swamp where I once had a molar. I couldn’t move my head without making more pain. So I wrote my answer: No. It came out in a messy scrawl, which surprised me because nothing had happened to my hand. And it was a lie, but I did not see a choice. Mark hardly needed to point out that everyone involved would take his word over mine. He’d been introducing himself right and left as a clinical psychologist from ASH. As Dr. The county medical community is tiny; friends or not, the shrinks know each other. Even without accusing anyone, I had to produce an account of the accident three separate times. I varied the wording slightly so it didn’t seem rehearsed: Sliped in wa ter & felll on cuonter top. It ws gratnite. The night supervisor got the third set. He frowned. “You might have a concussion,” he said, and stared into my eyes. “Any memory loss? Headache?” Probably and definitely. He had me follow his finger right to left. “Go easy on the wine for now, all right?” he said. * * * I didn’t know much about Mark’s parents but I did know that they didn’t let their children drink, not that they knew of. I’d heard cautionary tales about Aunt Trishie, who’d been married not once but four times in Reno under the influence, and Uncle Bart, who’d been so mad over a fender bender one December 25 that he grabbed the tire iron out of the back of his truck and “stepped on over to kick that driver some Christmas ass.” Mark offered these stories as examples of his own triumph over the family disease. He liked wine, beer, and cocktails, but he said he didn’t let them run his life. As proof, one of his specialties as a counselor was substance abuse. That night, I was putting dishes in the sink and running the tap when he told me he wanted me to lie down naked in bed and let him tie me up. After that, he would pretend to force me to have sex with him. I made a mistake. I didn’t think. I said, “If you want to do that, you’ll really have to rape me.” Next I knew, I lay spitting blood onto the tiles. Mark waited a half hour, till it was clear I wouldn’t get up. He had a glass of red wine to calm his nerves. When the EMT’s arrived, he introduced himself and said I’d been drinking. Everyone that night seemed to accept it, though as they worked on me they could have smelled my breath and known Mark was lying. * * * At the end of the tour, we faced a final corridor of offices for counselors, therapists, and administrators. It was locked. Here Heather began telling me about Mark’s predecessor: a female psychologist who’d been caught in a broom closet having sex with an SVP. “The orderlies had to pull them apart,” she said. She swiped her card key and got a red light; she frowned and tried again. “She kept screaming, ‘I can change him! I can change him!’” I wished Heather had waited to tell the story in private, not when that throng of SVP’s stood just a few feet behind us. “Does that happen a lot?” I asked. Heather didn’t exactly answer. “She’s at a super-max up north now,” she said, swiping the card several times in rapid succession and getting nowhere. I felt the SVP’s laughing behind us. “As an inmate, I mean. She’d been muling drugs in for the guy. And on a similar note, that’s why we don’t take writing tutors from college—the SVP’s are too smart, and they’d eat undergrads for lunch. We really need you, Beth.” “Which prisoner was it?” I asked. Heather rubbed her card key against her pants as if to clean it off. “Is he here now?” About five feet behind us, I heard the men rustling. Mark, meanwhile, decided to help; he took out his own key card and reached around Heather. It slid gently in and the lock clicked. “Ah!” Heather exclaimed, as if she’d just seen Jesus. Mark smiled in that humble way that isn’t humble at all. “Does it happen a lot?” I asked more loudly. “That sort of … affair?” We stepped into stale air that smelled of books and dying houseplants, the low murmurs of therapy sessions behind heavy steel doors. In Heather’s office, I noticed the ugliest dick-glyph of all. It was long and straight and uncircumcised, and it stretched over the front of her desk as if it owned the place. I wondered how it had got there. “Anyone on staff who gets involved with a patient is immediately fired,” Heather said, as if that were an answer to a question I hadn’t yet asked. “And loses their license.” * * * Mark took some personal days. He called my bosses and the clubs whose events I’d be missing and told them I was hurt. He relayed their good wishes as he fed me smoothies and Vicodin. He said Heather sent me a hug, which seemed improbable. He gave me the hug and it made my heart skip with adrenaline. “She really likes you,” he told me. “She says you’re a gem.” I can make a difference, I thought as my face throbbed and my vision faded in and out. I am a gem. Mark gave me another painkiller. I was dreamy on Vicodin. On Vicodin I couldn’t run away if Mark hit me, but on Vicodin I didn’t really care. Drawn by the human-in-pain pheromone, Pearl spent hours sleeping on my chest. She knocked the smoothie cups out of my hands. Mark didn’t complain about the mess, and Pearl rubbed against him. He was treating me nicely. He was very careful, carrying wire cutters in his pocket in case I started to choke and he had to get my mouth open fast. He acted so easygoing that I started to question my memory of that night, starting with my reaction to his request—that’s how I had to think of it—for bedtime activity. Maybe it was a harmless fantasy; maybe it was even selfless. Maybe he just wanted to understand his patients better and do it in a safe way with me, his partner. But of course (I pulled myself back through the fog) it hadn’t been at all safe for me in the end. At my desk in the small second bedroom, I slogged through insurance forms. Date of first injury; first day of last menstrual period; pre-existing conditions; parents’ causes of death, unless living; single, separated, married, divorced … Writing was almost as difficult as speaking. The paper felt very far away, and the fingers holding the pen were not mine. Water fell onto the page and I realized I was drooling. I mopped at my mouth with a Kleenex. My parents were dead and so was my brother, in a single car crash. Memories raced more vividly than the events of the now. “What am I supposed to call them?” I’d asked Mark as we were walking through the parking lot for the first time, toward the squat brown buildings of ASH itself. “If I can’t call them prisoners, I mean.” “Patients,” he said, and at first I’d heard patience, a command. Even now, I felt the men’s eyes on me, the SVPs’. I thought I remembered one more thing from that day: a disabled man with an eager smile but a glazed expression. His grin stretched so wide I could see he didn’t have a single tooth left in his mouth. This was clearer in my mind than my last menstrual period. Mark had said that almost all the patients at ASH had substance-abuse issues that fueled their predation or contributed to their mental disabilities. His mission was to give them the tools with which to fight their own cravings. “Oh, it’ll just take a lil’ time,” I heard him slurring into the phone one night. “She’s gonna be fine. I’m takin’ care her myself.” A brief silence, the sound of a glass touching down on the counter, then, “Email me you’ recipe for that tomato soup we used to have when we were sick, will you? I think she’ll like it.” Oh, he was talking to his mother. Who thought that her son never drank. When he hung up the phone he noticed me watching him. Surprisingly, he grinned. “Yeah,” he said, “you’re funny-lookin’, but you’re my funny-lookin’ girl.” * * * When I finally met Mark in person after a few weeks of e-dating, when he drove down and stayed in a motel, he told me he loved me. “I’m your family now,” he said. He seemed terrifically romantic. When I said it back, a week or so later, he wept. Either his mother never sent her recipe or Mark decided not to make it, because the soups he gave me were Campbell’s. He’d open a can and heat it in a bowl in the microwave, then sit companionably watching me eat while he had a sandwich and drank one or two beers. And then one or two more. And some wine and some whisky and I must have been really confused because no one can drink that much in an evening and not pass out. He’s fooling himself, I thought at night, as he lay snoring beside me and I was too nervous to move. He doesn’t know what happens when he drinks. He doesn’t really want to pretend-rape me. Alcoholism is a disease. So is violence. But the clichés ran out. I didn’t want to think of him as sick and hurt. I was hurt. And he hadn’t been drunk until after he hit me. I tried to slide out of his arms and join Pearl on the sofa, but even in sleep he held on hard. * * * About a week after that night, my friend Leslie, a fellow grant writer from the Arts Center, came to visit. She brought a bouquet of white roses, a card, and some new insurance forms. I took these things from her and asked, “Want to sit down?” It came out as Wahssiddown. Low and hissing. Leslie looked startled. She hadn’t heard me try to speak a sentence before. She covered by telling me that the card had been made by Earl, one of the few men in the Arts Center program. “I like Earl,” I said. Earl had glasses an inch thick and more hair growing out of his ears than on his head. He’d painted a creature in the mongoose family with lipstick and curly eyelashes, half her limbs bandaged up, and a cloud of punctuation marks circling her head. “Hang in there, your too pretty to die,” it said. Inside were plenty of teasing good wishes from teachers and students, all of whom I imagined had perfectly happy sex lives and work lives and stories to tell, properly spelled or not. I loved them all, in a big bubble of opiate good feeling that made me weep. “Beth?” I realized Leslie had been talking for a while. “I’m shorry?” Stupid reflex, apologizing through the wires holding my mouth shut. I had to dab at my lips again. The corners were cracked and chapped from the drooling. “What?” Whaa. “The man of the house. Is he taking good care of you?” She said it brightly, cocking her head toward the clatter in the kitchen. Mark was running water and banging around with a kettle. He didn’t like guests but he was going to make tea for this one. I grunted Yes. Leslie pitched her voice so Mark could hear: “You know he emails us about you every day?” I did know, and I didn’t like it, but I couldn’t answer right away. Leslie was wearing blue crystal earrings that made prisms of the dust motes in the air and distracted me. They looked especially nice under her cropped gray hair. Little things, I thought. Little things were all I noticed anymore, maybe all that mattered. That would be a nice lesson to take away from this experience. Mark brought in the tea: a cup for my friend, a glass with ice and a straw and a pill bottle for me. He was wearing his favorite T-shirt, the one for the movie Alien. “So what do the doctors say?” Leslie looked at Mark while she stirred sugar into her cup. She was finding it painful to look at me. “Is our girl healing?” I may have fallen half-asleep by then. I remember Mark’s voice saying something, and Leslie asking exactly how I’d hurt myself, since Mark’s first call had been vague; but I don’t recall his answer. Then a rattling sound as Leslie picked up the bottle of Vicodin, and her voice asking, “Should she really still be taking these?” Mark’s voice reassured her. * * * In two weeks I’d healed faster than I would have expected, at least enough to go back to work. My mouth was still wired, my face splotched green and black, but I had learned to speak with a sort of surly fluency. The retirees made a point of stopping by my desk with little tokens, mostly candy and cookies they’d made. “Sweets speed the healing,” they said earnestly. “Feed your pretty face up again.” They were so kind that I couldn’t tell them I wouldn’t eat solid food for another month. Sometimes I had to lock myself in the bathroom and cry. I was afraid to go home. Mark drove me everywhere. I was in pain and I craved Vicodin with every fiber of my being. Sex was going to come up soon, I could tell; he had begun dropping hints. I didn’t like to think about what he might expect after weeks of nursing me from an injury he didn’t seem to remember he’d caused. I didn’t even want to do it with him the regular way. Somehow the weeks of recovery had turned me against him as even the violent night hadn’t done. If only I’d been honest with the emergency team at the hospital … but everyone knows that if onlys are a big waste of time. My medical records said I was clumsy, and the EMT’s and doctors and nurses would all, every last one, believe Mark. He was one of them and I was a liar. It was what they would say, anyway. Some days I thought, Maybe Mark has changed. Maybe the violence scared him as much as it scared me. Maybe things—everything, all the undefinable things—would be different now. Other times, I thought that if Mark guessed that I wanted to leave, he might hurt me worse. I took to hiding my wallet in a new place every night. I got cash out of an ATM during my lunch hour and stashed it in my file drawer at the Arts Center. I kept my mind a blank so he couldn’t read it. I didn’t have a plan for leaving, but I was preparing to have a plan. I had sex with him and pretended it was okay. He didn’t have to rape me; I went along with everything. The jaw wires were as good as handcuffs anyway. At six weeks, the wires came out, and the doctor said I was safe to teach my first class at ASH. My option to say no had disappeared somewhere among get-well cards and smoothies with straws. The board at the Arts Center was excited; every prison worth its salt those days had a writing program, and every local arts organization was involved in one. Leslie was especially proud that I was proving the Center wasn’t just for wealthy retirees. It had real grit and commitment. “We can apply for so many grants!” she said—always the first thought of a not-for-profit arts administrator. “It takes a special person to do this kind of thing. I know I don’t have it in me.” I couldn’t bring myself to tell her I didn’t think I did either. I was afraid to teach at ASH and I was afraid of what would happen at home if I didn’t. I was a sniveling weakling and I would never get away. So Mark and I drove again through the hills to the huddle of brown boxes and razor wire. It didn’t seem much time could have passed, though the sweetpeas were gone. I let the guards take my Arts Center tote bag, which they upended so they could examine every pencil that fell out (no pens—I’d been warned they could be melted and shaped into weapons or drug paraphernalia). I blushed when they examined my i.d., then looked at my face. A greenish tint lingered in my skin, and my lips were still scabbed from the drooling. I looked horrible. Worse, vulnerable, like a walking billboard for abuse. I couldn’t believe there was anyone who didn’t recognize it in me. They didn’t even comment on my face. “You can’t use these pencils.” A pimply young guard held one up triumphantly. “Metal on the ends! Dangerous!” He took out a pair of pliers and began snipping off the erasers and the metal bands that held them in place. I realized my hands were shaking. The older one said, “You won’t try bringing these in again, will you?” “No.” I clasped the hands together. “She’s going to help the men write their memoirs,” Mark said as if to shame the guards, just as Heather came through one of the locked ward doors. She was in another brown pantsuit, this one with pink grosgrain ribbon bows on the lapels and cuffs. She greeted me by taking both of my hands in both of hers, a counselor’s gesture of warmth. I wondered what she thought of Mark and if either of them was a good therapist. “This is going to make such a difference, Beth!” she declared; but she was looking at Mark. Apparently I was painful for her to see, too. “What you’re doing is going to change lives.” (“Hey, lady …”) I pulled away and busied myself finishing the sign-in. I had a bad, sweaty feeling all over. It might have come from nerves or fear or the fact that when Mark fed me my latest Vicodin I spat it out surreptitiously, not wanting to show up at ASH drugged. Instead, I was in withdrawal. “You okay, ma’am?” the older guard asked, and then I knew how bad off I was. If I’d acted close to normal, he would have called me miss. “You want some water or something?” I shook my head and hurried to finish the form. As I wrote my name, I saw the letters come out foreign and distorted, the way they had been that first night. I wondered: Was it possible to become an addict in under two months? The person who could give me the answer was a person I should not ask. Mark said, “She’s a trouper!” and loaded the mutilated pencils back into my tote bag. A guard buzzed us through the first door, and Heather led the rest of the way with her key card. We walked down corridors still—or again—rippling with graffiti and the paint used to disguise it. I did not look around this time, but nonetheless I got that sensation again, the creeping at the back of my neck. Men were coming out of rooms and offices, staring. Following us with that shuffling soft scuff. “Hey, lady …” I heard it again and again. I tried to ignore what came after. Soon enough Heather unlocked the classroom. On one of the grubby computers, there was a newly scratched penis and also the word to identify it. This was both depressing and a little uplifting; it showed at least one man could write as well as he drew. Eight pupils were waiting: white, black, Latino, all tilting back at a dangerous angle in their scuffed plastic chairs. Three looked disabled and the rest had the sharp eyes of SVP’s. A man with hair sprouting in uneven tufts asked, “Can we play video games?” He pointed to a computer, smiling with naïve hope. He had no teeth. He wasn’t exactly the man I’d seen in my visions, but he might have been. There were so many of them. Mark and Heather exchanged a forbearing look. “Not today, Roy,” Heather said with professional cheer. “Take your hand out of your pants, Roy,” said Mark. Roy obeyed, his grin now sheepish. “Sorry, Doc Mark.” My jaw throbbed. I’d had no idea Mark had an affectionate nickname here. It made me nervous. I took a deep breath and tried to steady myself by counting out a slow exhalation: One, two, three … When I made it to ten, I would begin the speech I had practiced. My speech was about the joy of self-expression and how freeing it could be to tell a story honestly and with feeling, yet so artfully shaped that the reader would experience exactly the emotions the writer wanted to evoke. When I’d practiced at home, I almost believed it. I almost thought it actually might help make the SVP’s stop hurting people weaker than themselves. But then I looked at Mark and knew I would have to do much more than encourage them to write memoirs. “Beth!” Mark said rather loudly, up close to me. “Are you sick? If you don’t want to do this anymore, just say so.” He was trying to be gentle, but I heard the threat beneath the veneer of kindly Dr. Mark, therapist. If you don’t want to … I was supposed to double down and swear that I did want this. But I couldn’t push the words out of my throat. All eyes were on Mark and me. The men knew what was happening—at least, the predators did. Heather looked puzzled, in her no-nonsense brown suit with its girlish pink ribbons. “Mark,” she said, “Beth hasn’t uttered two words since she got here.” He put his hand on my shoulder. It felt heavy and hot. “What do you think, Beth?” His voice buzzed like the air before a storm. “Are you going to do this?” * * * “Poor little thing,” said the seniors at the AC. They said it over and over for weeks. “How are you feeling?” Over and over, I shrugged and smiled and said I was fine. I knew they weren’t thinking of my jaw so much as the fact that the Claddagh ring had disappeared. I was therefore obviously without a mate. There were others, though, who didn’t pity me for being single. Women stopped by my desk to confide that some man in their past had hurt them, that they’d been raped, that their bones and spirits had been broken in the name of love. “It’s so much nicer when the need for a man goes away,” they would say. I was sure they were right. But still, somehow, I kept hoping, and probably will keep on hoping, that I might find somebody whose kindness will draw out the kindness in me. I want this so badly that sometimes, even after all of these years, I wake up in the dark with my heart pounding, as if it knows I’m too late.  Susann Cokal is the author of Mermaid Moon (Candlewick 2020), The Kingdom of Little Wounds (winner of several national awards, including a 2014 silver Printz medal from the American Library Association), Mirabilis (Penguin Putnam), and Breath and Bones (Unbridled). Her short stories have appeared in journals such as Electric Lit, Cincinnati Review, Prairie Schooner, Hayden's Ferry Review, Quarterly West, The Journal, and many others. She is also author of articles on Jeanette Winterson, Georges Bataille, The Sopranos, supermodels, zoos, and other aspects of high and pop culture. She has also published dozens of reviews in The New York Times Book Review and is editorial director of Broad Street Magazine (broadstreetonline.org). Her home on the web is susanncokal.net. 5/27/2020 A Fair Amount of Ghosts by Zach Murphy soleir CC

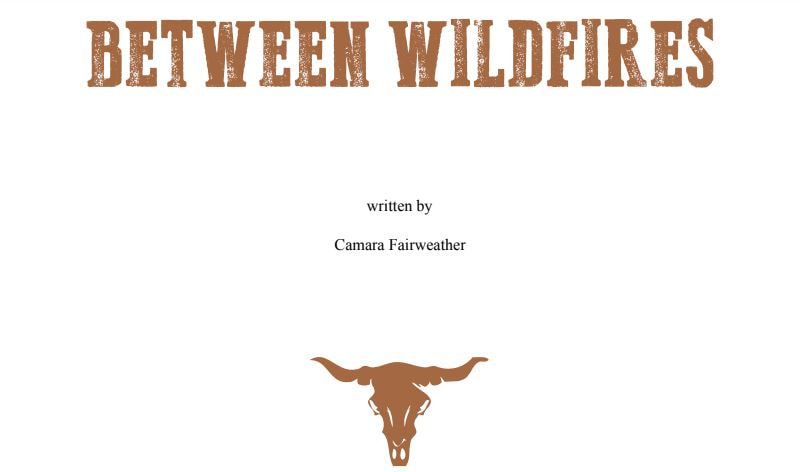

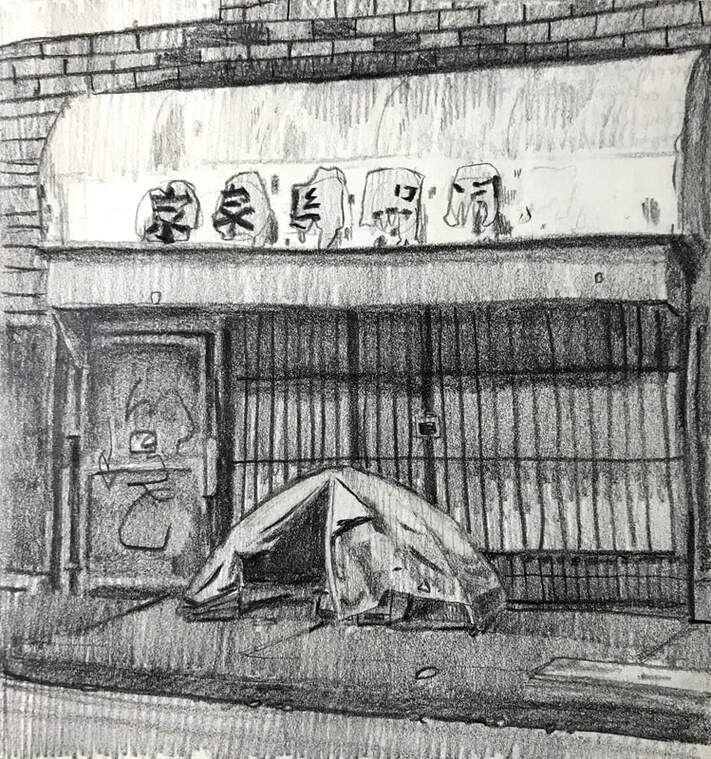

A Fair Amount of Ghosts He plays the trumpet brilliantly on the corner of Grand and Victoria. He doesn’t look like he’s from this era. He’s impeccably dressed, from his crisply fitting suit to his smooth fedora hat. There aren’t many folks that can pull that off. He’s cooler than the freezer aisle on a sweltering summer day. He performs the type of yearning melodies that give you the goosebumps. I’ve never seen anyone put any money into his basket. There’s a formidable stone house that sits atop Fairmount Hill. It’s been for sale for as long as I can remember. The crooked post sinks deeper into the soil with each passing year. It isn’t a place to live in. It’s a place to dwell in. There’s a dusty rocking chair on the front porch. It’s always rocking. Always rocking. I’m not sure if the chair is occupied by an old soul or if it’s just the wind. Maybe it’s both. I guess the wind is an old soul. This town is full of posters for Missing Cats. There’s one for a sweet, fluffy Maine Coon named “Bear.” He’s been gone for a while now. I’ve searched through every alleyway, under every porch, and inside of every bush for him. Sometimes I think I see him out of the corner of my eye. But then he’s not there. The rain has pretty much washed away the tattered posters. If he ever turns up, I worry that the posters will be missing. I met the love of my life in Irvine Park, near the gloriously spouting water fountain, beneath the serene umbrella of oak trees. We spent a small piece of eternity there together. We talked about whether or not the world was coming to an end soon, and if all of our memories will be diminished along with it. After we said our goodbyes and she walked off into the distance, I never saw her again. So I left my heart in Irvine Park. Zach Murphy is a Hawaii-born writer with a background in cinema. His stories have appeared in Peculiars Magazine, Ellipsis Zine, Emerge Literary Journal, The Bitchin’ Kitsch, Ghost City Review, Lotus-eater, WINK, Drunk Monkeys, and Anti-Heroin Chic. He lives with his wonderful wife Kelly in St. Paul, Minnesota. 5/27/2020 Artwork by Phuong Nguyen  Phuong Nguyen is an artist that currently practices in Toronto, Canada. She is primarily a painter and has completed her Bachelor of Fine Art at OCAD U in 2014. Nguyen is interested in people and the complexities and simplicities that come with being human. Working with mostly representational subject matter, she aims to evoke emotion, nostalgia, connection, and empathy. She has shown work in Canada, the U.S., and the U.K. soleir CC

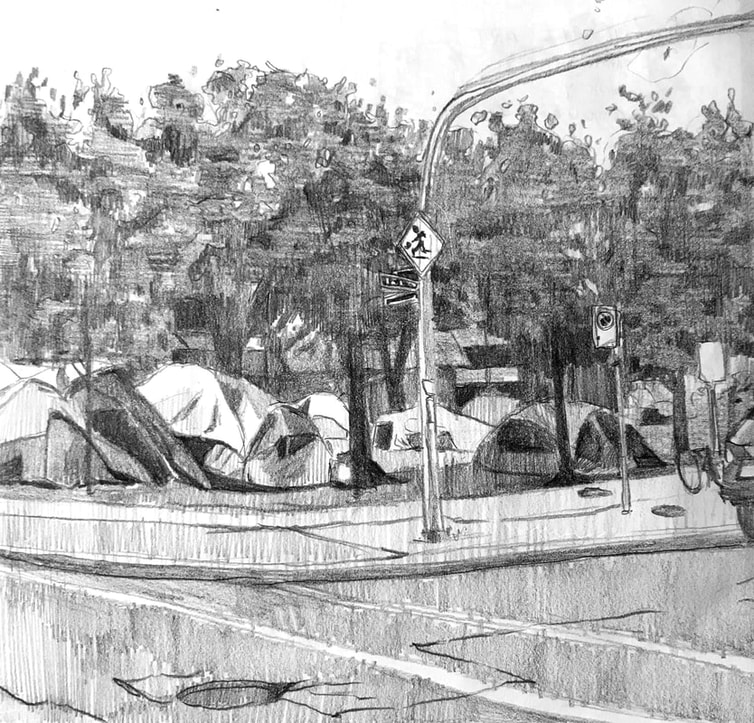

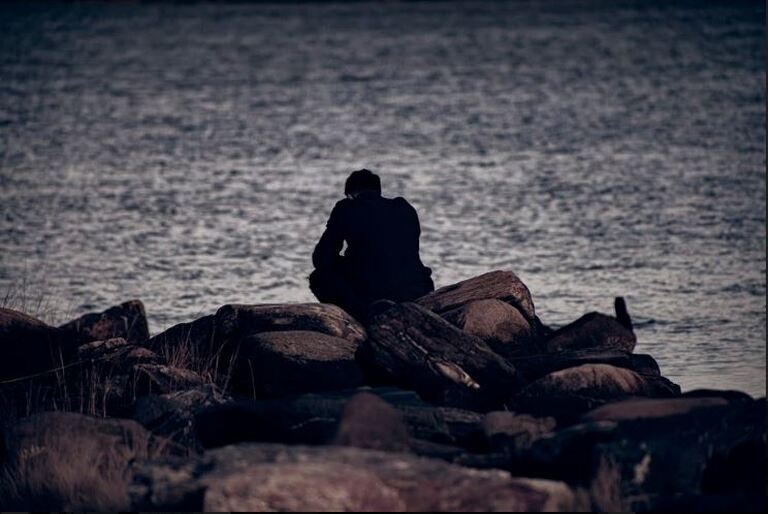

The Principle of Gentleness There are seven fundamental principles of Judo. The first is ‘Physical Training.’ A father takes his son to Judo class on a Sunday morning. The boy doesn’t really enjoy sports, much preferring to be indoors watching Thundercats on TV, he doesn’t have many friends. The son will be picked on at school for being quiet, worries the father, who doesn't want to re-live his own childhood vicariously. Kids and parents sit on benches around the mats, waiting for the class to begin. The Sensei steps out to the middle of the mats, filling up the space, the room hushed before him. The father wishes he looked more like Sensei. He thinks that Sensei looks the way a father should look; he’s at ease, but ready to fight. He is motion at rest. This is ‘Shizentai’, the natural posture of Judo. The second principle. “Who wants a fight?” Sensei asks the kids at the class, who respond by rushing over and jumping on him. All except one. The boy looks at his father for a cue, some sort of instruction but receives none. It’s your choice are the words that pass silently between them. The boy gets up and runs to the mats. Arriving last of all he stands on the periphery of the melee, just slightly out of reach of the fun. The same way he’ll stand at so many parties as he gets older. ‘Courtesy’ is the third principle: everything in Judo must begin and end with respect. Only through courtesy can we recognise the dignity of another’s personality. ‘Sen’ is the fourth principle, meaning to take the initiative. *** The fifth principle - ‘Kusushi’ (breaking balance). In Judo, victory or defeat is attained through ‘Kuzushi.’ It is the manner in which balance is destroyed, leaving the combatant in a vulnerable state. Years after Judo lessons have come to an end, the father and son take a holiday together in Barcelona. The father has tried to worry less about his son as the years have passed. The boy being picked on at school, having no friends. None of these fears came true. Instead, new ones sprang up in their place, multiplying like gremlins. The son is a teacher now. He still watches retro cartoons from the eighties. But they have more in common than the father ever thought they would. They both like pulling the wings off a roast chicken. They both listen to Tom Petty, read Stephen King. They’re both lousy at assembling furniture. They talk comfortably of nothing in particular while crammed in at the bar at El Xampanyet, eating boquerones and croquetas, their glasses generously refilled with the sparkling wine for which the place is named. The father feels unsteady for a moment on his feet. Just the wine, he tells himself, just the heat, it’s crowded in here. Getting old, he tells himself. He’s feeling much worse by the time they leave but says nothing to his son, doesn’t want to spoil the trip. The sixth principle of Judo is ‘Stability.’ A man falls easily if his centre of gravity is disturbed by an external force; it can be something as minor as stepping on a pebble. After the father’s first stroke, he makes a reasonable recovery, with some loss of movement. He is still able to live alone, until the first time he forgets who his son is. “Have you come for the newspapers?” he asks him one day, his face blank and lolling and expectant, like a good-natured old Beagle, but nothing like the man his son knows. The seventh principle, ‘The Principle of Gentleness’ is the overarching concept of Judo. It means that victory is not won by applying superior force but rather by utilising the force applied by an opponent. If your opponent steps towards you, you take a bigger step backwards and take him with you, using his own force to break his balance. The son visits his father in the care home. He speaks to him as he always did, regards him with the same dignity. Tries to recognise him. “There’s a thief coming in to my bedroom at night.” The father says. “He wears a cap on his head.” He’s describing his son, the uniform he used to wear to school. It is not the first time he’s said this. The son fights the urge to shout at him, “No there isn’t! You’re talking about me.” But he doesn’t. Instead he plumps his dad’s pillow and props him up so he can see the TV which plays on mute all day. Then he refills the plastic cup of water by his bedside, and says he’ll get the nurses to look into it. He thinks of a passage he once read: Death does not send you any letter, he comes sneaking just like a thief. Perhaps the thief is real, and his father senses him getting closer to his prize. But death has already sent them a letter; he sent it to El Xampanyet on that warm night in Barcelona. Now Death is just waiting for the man to fall gently into his arms. Death is late for his own party, and where - thinks the boy - exactly, is the courtesy in that? Rick White lives and writes in Manchester, UK. His work has been published in Storgy, Barren Magazine and Anti-Heroin Chic among others. @ricketywhite 5/27/2020 Photography by Donald Gjoka  Donald Gjoka is a landscape photographer and drone pilot whose interests lie in the stories the environment expresses. Donald uses photography to capture memories of his life and the places he's traveled to. To see more of Donald's work, visit @dongjoka on Instagram. Follow PLAY > Apart from the usuals who wandered in and out to sift through old records the shop was unusually quiet. Marcel, the sales clerk, was leaning back on the brick wall behind the register, rolling a joint between his fingers. He took the fixings, rolled, licked, and twisted, then placed the cigarette in his mouth. The rose-colored tip glowed gold as his thumb stroked the wheel of the lighter, before browning, and turning black. He stared out the display window as he smoked. The evening sky was a pure, uninterrupted pink, and when the light autumn wind stirred there came through the open window the heavy scent of flowers from the market. Through the seam of smoke he could see the constant flicker of men and women passing by on the pavement – the shadows of birds fluttering in-between them. He had always been something of a daydreamer. He was used to standing by himself, staring into space, and thinking about nothing in particular – as if he really were the prey of aimless days. He turned away from the window after a while, noticing someone moving faintly in the periphery of his vision. His friend, Saoirse, was coming out one of the back rooms. She was carrying, in her arms, a stack of cardboard boxes filled with cassette tapes and vinyls. ‘Hey troublemaker,’ he said, watching as she put her boxes down on the carpeted floor to adjust the red bandana that was tying back her tight ringlets of greying-ginger hair. ‘Hey yourself,’ she smiled, stepping slowly out from the doorway. ‘They told me you collapsed.’ ‘I did,’ she said and a muted sunbeam cut through her hanging breath. ‘These legs of mine sure used to be a lot more cooperative back in the day.’ ‘Here,’ he took the joint from between his lips and extended it, ‘you wanna hit?’ ‘That’d be grand,’ she said before taking a small, slow draw. The paper crackled slightly as she inhaled. She was a sweet old lady – a little apple blossom from Ireland – and the shop belonged to her. She mostly dealt in second-hand vinyl though she also carried a selection of vintage instruments which had retained a certain charm through the years. The people who came to buy these were young mostly, hipsters and alike, manifesting nostalgia for times they had never actually lived. ‘I didn’t think you’d be, like, back on your feet so soon.’ ‘I’m not exactly the stay-in-bed type.’ ‘I know,’ he said, ‘but don’t you think you could be taking it, I don’t know, a little easier?’ ‘Ah now, it was only a light sprain.’ ‘I still think you should be resting.’ ‘And I think you shouldn’t be worryin’ about an old woman like me. There’s no sense in thinkin’ the worst, Marcel. It doesn’t help with anythin’ you know.’ ‘Yeah. You’re probably right.’ They passed the marijuana between them as they talked, shooting the breeze about one thing or another until there was nothing left but burnt-out ash and smoke receding into the air like ephemera. ‘I wanted to ask you something before you go,’ Saoirse said when it was time to close up. Marcel looked back over his shoulder. He had his hand on the door, ready to leave. ‘Earlier, as I came in, I saw you starin’ out the window there. What is it you were lookin’ at?’ Marcel waved goodbye as he left out the door, sounding the lintel over the mantle. ‘Looking out for what’s coming is all.’ ‘That’d be a fine thing,’ she said but Marcel had already gone. She frowned, revealing the valleys of her ageing face, ‘Too bad no one ever sees what’s coming.’ Marcel started toward the bus stop with his hands in his pockets, his feet falling against the pavement, the numbing air turning his breath to steam. >> FAST FORWARD >> The night was carrion black by the time he stepped off the bus and walked out onto the slick wet pavement. It was late after sunset but still far from dawn. He heard the doors shut behind him, then the bus pull away, it’s tail lights fleeting crimson into the distance, leaving him standing on the curb of the street – just a silhouette under the lemon streetlight. It had started to rain so he lifted his hood up over his head, walked to the crossing, pressed the button, and waited. Cars were running fast on both sides. He didn’t feel like going home, back to his small, empty apartment where all he seemed to do was cry. In that moment, as he waited for the red light to turn green, the only place he felt like going was somewhere loud enough to drown out his own thoughts. He noticed a bar on the other side of the street. It was a small place, set back from the main strip. Marcel walked in and let the door slam behind him. The place was a real dive – its walls were threadbare and everything seemed to be falling into dereliction. It looked like the kind of hauntingly vacant tableau people came to when sobriety started to feel too oppressive – too much like hard work – at least compared to the hollow lure of spirits and cordials. The same kind of people whose lives were so damn complicated they couldn’t stay on top of them in any meaningful way that didn’t make it look like their lives were just going to get more complicated. He tried hard not to think about that as he made his way to the bar and leaned against the counter but quickly found that trying not to think about a thing paradoxically only created a preoccupation with it. ‘Whiskey,’ he said, bringing out his wallet. ‘Sure,’ the bartender said in that not listening kind of a way. Marcel handed the guy a note and after a moment, the bartender slid his drink across the bar. He stared at his reflection in the bottom of the glass. He was a tall and lean twenty-something. His skin was the colour of pine and his face was obscured by disheveled black hair which bathed his deep set eyes in shadow. He stared for another second then finished his drink – tired to death of looking at his own reflection and hating what he saw. He wished, with each successive breath he took, that he could be someone else entirely; someone without so many insecurities. He had imagined, when he came in, that the loud music and drinking would have made him happy or at least have taken away some of the self-loathing that seemed to follow him everywhere he went like a vague smile, but he had been wrong. As he was considering getting up to leave, he noticed a man making his way over from the other side of the room to sit beside him at the bar. Even from the momentary glance Marcel caught of the man, he looked quite stunning. He was dressed in drag, his long hair lying over one shoulder of his short dress and all his features illuminated perfectly in the neon light from the bar. ‘A bird with one wing can’t fly, honey,’ the drag queen said, staring down at the empty glass between Marcel’s knuckles, ‘so how about I get you another drink?’ ‘I probably shouldn’t.’ Marcel said, shaking his head, suddenly very aware of himself. ‘One won’t hurt.’ ‘Is that what Eve said to Adam?’ The drag queen half smiled, full lips parting over perfect white teeth. He lifted his head to catch the bartender’s attention, ‘Two more whiskeys.’ ‘Thanks.’ Marcel said, receiving the drink when it came. ‘I’m wondering – do you often buy drinks for the strangers sitting across the bar from you?’ ‘Only the ones I can’t seem to take my eyes off.’ ‘I’m starting to think you might be trouble.’ ‘Well, you know what the trouble with trouble is?’ He leant forward to whisper in Marcel’s ear, ‘It’s actually a lot of fun!’ Marcel tried to suppress his grin, ‘What’s your name anyway?’ ‘Most people just call me Zizi. What about you?’ ‘Marcel.’ ‘Marcel,’ he repeated slowly, enunciating each syllable, turning the word over on his tongue, ‘that’s a sweet name. Were you named after the artist?’ ‘Marcel Duchamp. If you can call him an artist, then yeah, I was.’ ‘You don’t like him?’ ‘It’s not that I don’t like him exactly,’ Marcel paused, ‘I just don’t think he was all that. I mean, what’s so special about all the objects people take no notice of? Trust me. There’s nothing distinguished about neglected things.’ ‘I don’t know. I always thought there was something kind of poetic about the way he challenged people’s preconceptions – and if Picasso despised him then he must have been doing something right.’ ‘Sometimes I think he was just pulling a fast one on us, encouraging our capacity for illusion or our propensity to believe some things are more deserving of love than they actually are.’ ‘Oh honey, the man died half a century ago and we’re still talking about him. Even after all those years we’re still showing his art in galleries. That’s not an illusion.’ ‘I’m pretty sure you didn’t come all the way over here to talk about twentieth-century art.’ ‘You’re right, I didn’t. As much as I enjoy the avant-garde,’ he laughed, motioning at his drag, ‘I actually came over to see over to see if you were okay. You looked like you were having a rough night.’ ‘I can’t help it. I honestly wish I could.’ Marcel said, leaning his head back to stop the tears, which had begun to gather in his eyes, from escaping. ‘I feel like all the sand at the bottom of an hour glass or something. I feel like I’m coming undone – like I’m losing my fucking mind all the time! And, I don’t know, I just don’t want to feel like that anymore.’ ‘What do you want?’ The drag queen asked, running his hand over Marcel’s. ‘To get out of here.’ >> FAST FORWARD >> They kissed, turning over and over on their way back to Marcel’s apartment, heavily cross-faded and entwined in each other’s arms. Marcel liked the way that Zizi kissed him – so hard and vicious like he could have drawn blood. When at last they reached the apartment door Marcel looked around for his keys. The door creaked on its rusted hinges and paint fell in small fragments as he opened it. He had forgotten to close the window before leaving that morning. The apartment was cold and dark inside. In the summer, when the sun had been shining and there were great bursts of leaves on the trees, Marcel had woken up to a self he deemed worthless and climbed out of that window. He remembered sitting on the hard windowsill, his bare feet dangling over the pavement for what felt like forever but what was – in actuality – no more than a few soaring moments. He walked over and latched the window shut, but even shut he could still feel the window framing all the pain and despair and self-loathing he had built up inside. He had first realised he was depressed when he was thirteen. His parents had divorced and it seemed as though every single shred of joy and irreverence from his youth had been tarnished or devoured completely but the cold austere reality of living with his mental illness. He had spent most of his adolescence in psychiatric wards, staring day after day at the same white walls, finding it difficult to make friends or form lasting relationships. And when he realised that he was attracted to men he thought, fuck - another reason to hate myself. Zizi pressed slowly up behind him. His fingers dug in just under Marcel’s ribs and the honey of his breath fell fast against the back of his neck. Marcel turned around – his heart beating fast -– and they kissed again – as fervently as before. He couldn’t quite explain it but while he was being held in this stranger’s arms it was as though his insecurities simply melted away. For a few moments, he wasn’t ruminating on his own neurosis or crippling self-doubt. He wasn't caught up in the kind of masochistic thinking that had led him tumbling down the proverbial rabbit hole of antidepressants and half-hearted suicide attempts. The intensity of each brush of their lips demanded that he was mentally present, unencumbered by all the brutally bleak shit going on inside his head. Zizi moved his hands slowly down Marcel’s body and slid his shirt off his shoulders. Marcel smiled, picking the man up in his arms and carrying him through into the bedroom, holding him like la pieta. As he laid Zizi down, his spine relaxed and his feet arched into the cottony nest of the bed. Marcel climbed on top of him, his eyes gently expectant as they continued to undress, throwing their clothes wherever. >> FAST FORWARD >> Marcel woke the next morning to a small indentation in the bedding and the lingering smell of women’s perfume. He sat upright and sighed. The morning light, which shone through the curtains, cast his shadow across the bedroom floor and as he sat there, still half asleep, he found himself wondering whether his own shadow thought he was worth following. He yawned – his arms subconsciously reaching out for someone who was no longer there. Sometimes, he wasn’t so sure. << REWIND << The drag queen moved with a particular equanimity, swinging the covers off his body and standing up with ballet posture. He tip-toed around the room, picking his clothes off the floor – trying not to make a sound – as if the bedroom were a china shop, and he a bull. Impatient to leave, he unravelled his little black dress with the cut out décolleté at the back and ran his arms through the fabric, feeling the sensation of each thread and fibre as they lightly cascaded over his skin. He was doing what he had always done when he woke up in a stranger’s bed – panicking and running away – giving in to the little voice at the back of his head. From an early an age as he could remember he had thought that running from his feelings somehow made him free. He was still far too young to realise that it was the very things he chose to run from that defined him in the end. He leant down, gathered up his heels, and finished dressing. He looked different in the daylight without all his female affectations; without his make-up or his long hair brushed neat or his genitals tucked between his legs so that when he was performing he could convincingly pass for a woman. A lot of people didn’t really get drag. And that was okay. Not everyone had to understand why it was that he put on lipstick. In a culture that told certain people they were less valuable than others, the simplicity of existing proudly and beautifully was itself a kind of resistance. And when you came right down to it, maybe that was enough. He turned, giving one last look to Marcel before he left out the door. He was sleeping quietly on the bed. His face looked peaceful, lying there softly between the sheets. >> FAST FORWARD >> Marcel walked into the small independent record shop where he worked. A guitar riff recorded on old reel tape was playing over the speakers. He thought the shop was empty at first, but then he saw Saoirse sitting in the corner of the room. She was resting with her legs crossed on one of the old burlap sofas, tuning an original 1964 red Airline in her lap, her hand strumming the strings. ‘Morning.’ He said. Saoirse looked up from what she was doing. Marcel was smiling at her but she knew – almost intuitively – that he wasn’t alright. She didn’t know exactly what was up with him – just that his smile had an immediately perceptible air of sadness. ‘What’s wrong?’ She found herself asking. ‘Nothing.’ He shifted slightly, shaking his head. ‘Really, I’m fine.’ Saoirse put the vintage instrument down then, without saying a word, she stood up, walked over to the door, and switched the sign from reading open to reading closed. ‘You say that but then you look so far away. I was just thinkin’, sometimes, even when you’re smilin’, you look so sad – like you’re not okay, emotionally, on the inside I mean.’ Marcel fell down on the sofa. Saoirse came and sat next to him. ‘You really want to know?’ ‘Yes.’ She said in a softer tone, pulling herself closer to him. ‘It’s so screwed up. I mean, I should be happy,’ he said, feeling totally inadequate, ‘but there are some days I’m so sad that I don’t remember what it’s like not to be.’ He buried his face in her chest and began to cry. ‘I must seem pretty pathetic right about now.’ ‘It kills me when you talk that way about yourself.’ She hauled his legs up onto her lap and wrapped him up in her arms, holding him in a hug that was so passionately felt she hoped it would make him know that he was wanted. He couldn’t remember the last time someone had hugged him. It felt nice – just to be held. ‘I should be the one taking care of you, not the other way around. I’m young and I really do have so much to be thankful for–’ ‘–and that only makes you feel even worse because you think you have no right to be sad. I know that feeling.’ She said, her breath slow and shallow. ‘Sometimes, these things, they’re hard to see, but a hell of a lot harder to talk about.’ II PAUSE  Camara Fairweather (b. 1998) is a biracial writer, illustrator, and poet from the United Kingdom. He has worked for BBC Three and flagship programs such as Newsnight. He is currently studying at the University of East Anglia. Self Portrait During Quarantine  Lily Arnell is a writer, artist and musician living in New York. She is the founder and editor of Silent Auctions Magazine. 5/27/2020 Little Witch by Michelle Houghton DaseinDesign CC Little Witch Let me be clear, I am a little witch. I’m told so every day, and I’ve begun to own it. I might even like the idea. I read once that witches were born in darkness. That we have to learn to wield that darkness in order to uncover our magic because magic will free us. Witches – Dangerously smart, beautiful, and bad. Their words speak to me, as if witches from across all different times and places gave their words just for me. As if my very own coven hides in the pages of books, their words comforting and advising. “We are all born a witch. We are all born into magic. It is taken from us as we grow up.” -Madeleine L’Engle But what if I grow up bad? Sweat drips through my flower print scarf headband. The lug wrench slips in my sweaty hand while I try to work the lug nut free. “Come on,” I whisper curse. No doubt Daddy put those lug nuts on with an impact gun. I can’t use the impact gun because I have to be quiet. I place my black lace up boots carefully on the lug wrench and step up on it to give a little bounce. Nothing. Adjust the lug wrench, stand on it again. My reflection catches on the truck, and I smirk at my newly dyed black hair and gleaming nose ring. The wart on the nose is so old school – witches wear nose rings now. Another bounce. The wrench and I slip off the lug nut and fall to the blanket that I cleverly placed under the jack and the tire, so the tools and I fall quietly. This isn’t my first rodeo with Daddy. Last time, Daddy almost killed me and someone in a blue car. Daddy’s getting worse. I have to do something or he’s going to kill someone. “We’ve all got both dark and light inside us. What matters is the part we choose to act upon.” - J.K. Rowling from Harry Potter and The Order of The Phoenix, Daddy likes his dark, he finds it in a glass of vodka and hold on to it all night. I find my dark in trying to outsmart daddy. But still, I put a shaky hand on my head for a minute and breath, wincing as I accidently touch the bruise under my scarf headband. “One down, thirty-one to go.” I whisper to motivate myself, as I unscrew the nut and begin on the next one. The sun is thinking of setting and apparently it wants to go out with flare, so it’s giving its all. I look around, nervously. The TV inside is blaring – covering for me like a true friend. My fingers aren’t working right, unscrewing a lug nut shouldn’t be this hard. I know it’s the stress of Daddy catching me that’s making all my muscles slow and clumsy. Otherwise I could rival any NASCAR pit crew for the fastest tire change – I lead a boring life and daddy approves of this kind of practice when he needs his truck tires rotated. I’m onto my third lug nut when Daddy yells from the house. I freeze, hold my breath, certain my heart is going to pound a hole in my chest. “KIRA DOUGAN!” I slowly bend and lower the wrench to the blanket. I self-talk a bunch of you got this, never taking my eyes off the screen door. If he comes out here, I’m done for. My hair hurts just thinking about it. “Com…” I try but my mouth is so dry it comes out as a croak. I conjure spit into my mouth and try again. “COMING!” I yell, willing my legs to move up onto the porch. Inside Daddy sits in his avocado velour chair and holds out his glass. “Fix me another, and don’t make it weak.” He pauses like it’s the first time he has seen my new look. When really, he just never remembers seeing it before. “Little witch,” he slurs. “You say witch like it’s a bad thing.” – Writer Unknown I grab the glass and notice his glazed angry eyes. Today must have been a bad day at work. He’s already angry and it’s not even 6 o’clock. If I don’t get those tires off soon and make myself scarce, we’ll be on Sherman’s Flats by 7:30 running a telephone pole slalom course. My hands begin to shake just thinking about the last time. I stop and breath again for a minute. We were feet from that pole and then a blue car passed us within inches, it’s horn blaring. When we got home, Daddy ran into the neighbor’s mailbox. They called social services for the seventh time, but Daddy wasn’t in his truck when the police got there, so there wasn’t a thing they could do. It’s always the same story. Nobody can do anything about Daddy. It wouldn’t matter anyway. The courts don’t mind that he’s a drunk, raisin’ a daughter. Momma’s probably been rolling’ in her grave, but there isn’t anything she can do either. Momma died of cancer when I was five. So, Daddy’s got rights to me until he hurts me and since he hasn’t killed or maimed me yet, everything is okay the way it is, at least that’s what the courts say. I won’t have rights until I’m eighteen. But I made it this far. I just gotten make it four more years. “What’s taking you so long!” Daddy yells. I grab the ice and fill half the glass and then pour in the Vodka all the way to the top - the way Daddy likes it. I pass the sink on the way to the living room, and the little witch inside stops me. I should add water to this. But I don’t dare. I keep moving. I hold the glass out to Daddy, and he squints and puts his big rough hands over mine. Squishing mine into the glass. “Did you put water in it?” he growls. I look him in the eye like I learned. Otherwise, no matter what I say he’ll think I’m lying. “No Daddy,” I whisper while silently sending magic vibes for him to believe me. “You have witchcraft in your lips,” William Shakespeare, “Henry V” He glares at me. I can smell the Vodka coming off his sweaty body – vodka and rot. “You think you’re smart, don’t you?” He slurs. “No Daddy, I know you’re smarter than me,” I say. More words I learned the hard way. Keep him calm, I think. Don’t engage. I once read to give the energy you wish to receive. So, I focus on low energy when I’m around Daddy. “That’s right,” Daddy says and waves me off. I go back in the kitchen and circle back, leaving through the back door and making my way around the house and back to the truck. I have twenty minutes before he’s done that drink. I work faster at the lug nuts this time. It took some muscle, and a lot of whisper cursing but I get the two far side tires off while Daddy drank himself angrier and then calls me in for another drink. Make drink. Get called names. Circle around back to the truck. I’m working on the third tire with my back to the house when I hear the screen door slam. I freeze. Nothing I do will make my muscles move this time. Daddy stumbles down the porch and grabs my hair turning me around inches from his beat red face. He’s menacingly calm – Probably that energy I sent him. “Dumb little witch,” he slurs and shoves me into the truck. The three-pump jack handle is between me and the truck, and it slams into my ribs as I bounce of it. I’m a shaking frozen mess. “A witch ought never be frightened in the darkest forest because she should be sure in her soul that the most terrifying thing in the forest was her.” – Terry Pratchett, “Wintersmith” Even though I hear the words in my head. I am still scared. They say if you kick a dog enough it will bite. I guess I haven’t been kicked enough because I still just freeze up. What the heck is wrong with me? Daddy grabs my shirt and drags me back to him. Don’t put out angry energy, I think. He sways before me. Spit flies into my face even though his voice is low. “You’re going to go in the house and get me another drink and then you’re going to put these tires back on.” I nod fiercely. I try to hurry and put the tires back on as Daddy watches and gives me a lecture about how stupid I am. Once I’m done, Daddy has me make him a To Go drink. With his To Go cup in hand, he zigs zags to the truck and carefully sets his drink in the cup holder. “Get in!” He slur-snarls at me. “’Tis now the very witching time of night, when churchyards yawn and hell itself breathes out contagion to this world.” – William Shakespeare, ‘Hamlet’ When we got out of town Daddy must have felt like the devil was chasing him, because he stomped on the gas pedal and never let up. Honestly, for a few minutes with the wind blowing in my hair and the world flying by, even my adrenaline was soaring, maybe not for the same reason. “Everybody deserves a chance to fly,” Elphaba, Wicked. Daddy whoops and hollers, as we flew down the open road bouncing between the two white lines like a pinball. When we turn onto Sherman’s flats, I take a deep breath and exhale slowly. The road is flat. No steep shoulders on the edges. Just telephone poles as far as you can see. And Daddy likes to make a game of zig zagging around them, off the road and back on, as fast as that truck can. Today, we only make it around the first two telephone poles before the truck gets into a fishtail. Telephone pole number three comes in slow motion. “Daddy!” I scream. But he’s crouched over the steering wheel like he didn’t even hear me. Manic joy is plastered across his face. Pole three comes at us fast and then slow, real slow, like time slowing slow. We’re going to hit dead center. I don’t know what comes over me. I just know that I’m not ready to die. I hear the words as if Glinda is sitting right next to me, “You’ve always had the power, my dear. You just had to learn it for yourself.” – Glinda, The Wizard of OZ. Somewhere deep in my soul, I feel it. I’m ready to bite back. “No!” I yell, grabbing the wheel, and yanking. Daddy hits the brakes, “Let go you Little Witch!” he roars. The truck swerves, gravel sprays everywhere, then the truck slid sideways and rolls in the air. At first, I see Daddy, head back laughing as we tumble. Then he’s gone. Glass is flying everywhere, and the truck is still rolling. Out of nowhere a light streaks into the truck as we tumble, it’s the bright, beautiful green of Elphaba, and it feels like an ethereal magic as it swirls around me and then disappears. When the truck finally comes to a stop, resting on the passenger side (my side), I notice Daddy’s not in the driver’s seat. I feel blood drip down my head and my right arm hurts a lot. Daddy’s about a hundred feet from the truck laying on the ground. His leg is bent the wrong way and his eyes are open, staring vacantly at the sky. I’m still strapped in my seat – the seatbelt on. And the first thought I have is, Who’s smart now? – Me I rest my head back and exhale. I don’t know if there is a heaven or hell, and I don’t know where Daddy ended up. But here’s the thing, I have a chance now, where I didn’t before. And while it feels wrong when I don’t even cry over Daddy dying. I also feel powerful. This is a Roald Dahl moment, “Those who do not believe in magic will never find it.” - The Minpins. I know I’m going to be okay now because I found my magic in the darkness and it set me ablaze. I smile my best witch smile because this little witch is free.  Michelle Houghton lives with her two children on a small horse farm in Ferrisburgh, Vermont. She is a 2018 graduate of Vermont College of Fine Art with an MFA in Writing for Children and Young Adults, where she won the Norma Fox Mazer award for stories that, like Norma Fox Mazer, asks young readers and even adults to confront tough issues.When she is not teaching children to read, you can find her conjuring stories in the woods of Northern New England. If you would like to learn more about Michelle please visit her website www.michellerhoughton.com 5/27/2020 Photography by Kelly DuMar Kelly DuMar is a poet, playwright and workshop facilitator from Boston. She’s author of three poetry chapbooks, 'girl in tree bark' (Nixes Mate, 2019), 'Tree of the Apple,' (Two of Cups Press), and 'All These Cures,' (Lit House Press). Her poems, prose and photos are published in many literary journals including Bellevue Literary Review, Tupelo Quarterly, Crab Fat, Storm Cellar, Corium & Tiferet. Kelly serves on the Board of the International Women’s Writing Guild (IWWG). She blogs her daily nature photos & creative writing at kellydumar.com/blog |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

April 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed