|

Rodney DeCroo's video War Torn Man is set against a mythical backdrop of toy soldiers and fire. Vivid images that are of no specific war so they can represent all wars. I was struck immediately by the echo and hollow sound to the vocal, I found this quite effective. The lyrics are hard and sparse. No wasted words or images. The story is as much about what he doesn't learn from his fathers experience as what he does. The song reaches its highest power during the spoken word portion that hits you dead in the heart and gut all at once. The lead in to this is a killer guitar solo that buzzes like a chain saw, creating a haunting pulsing video of the highest order! As a war vet myself and a man living with PTSD I appreciate this song for its honest look at a man and veteran. DeCroo does not claim to identify with his father or pretend he knows war in his blood like he was there himself. No, he is writing from the point of view of a son dropped in the middle of his father's nightmare. This has its own sad power captured perfectly in the video images of toy soldiers and strange surroundings. War Torn Man is a song that gets on you like gasoline and then dares you to dance too close to the fire. Visit DeCroo's Bandcamp page for more https://rodneydecroo.bandcamp.com/ and on Spotify.

Matthew Borczon is a writer from Erie, Pa. He has published five books of poetry including A Clock of Human Bones through Yellow chair review press, Battle Lines through Epic Rites, Ghost Train through Weasel Press, Sleepless Nights and Ghost soldiers from Grey Boarders press and Capp Road from Nixes mate press. He works as a nurse for adults with special needs and raises four children with his wife of 21 years.

Carlos Somonte, Netflix Alfonso Cuarón’s Roma: What You Notice When You Look [Spoiler alert—This review covers all events of the film.] What a rich pleasure Alfonso Cuarón’s Netflix film Roma is! The film is shot in black and white and is named after Colonia Roma in Mexico City. The slow opening credits of a patio being washed down prepare us for the approaching concentrated and deeply-nuanced viewing experience. (I almost gave up on the film during the lengthy opening credits and am so grateful I did not. If watching mop water slosh towards a drain bores you to the point of annoyance, fast forward through them.) The jet plane that appears overhead as the opening shot pans back and out reappears two times more, so watch for it. The film follows a middle-class Mexican family—Sofia, Antonio, their four children, and Teresa, Sofia’s mom—and their two Oaxacan, Mixtec-speaking, live-in housekeepers, Adela and Cleo, focusing especially on Cleo. The drama explores multiple tensions—well-off / poor, male / female, constraint / liberation, love / emotional absence. The family works Adela and Cleo hard from dawn to dusk. The movie begins by following Cleo through her tasks of a single day, from cleaning dog urine and feces from the patio and continuing through cooking, cleaning, laundry, fetching children from school, tucking them in at night, and even ironing after the family has gone to sleep. The four young children in the family make Cleo’s job seem especially bootless. We’ve just seen her working non-stop, yet hear the father, Antonio, who typically returns late at night after the children have undone Cleo’s hard work, complain to his wife about what a mess the house is. (Tellingly, Sofia doesn’t agree with him, perhaps knowing better than he does what Cleo is up against.) The movie creates a tension between the freedom of the street and the claustrophobia of the house. The family dog can only stay in the patio / garage. He bounces up and down behind the glass of the door whenever anyone passes or returns home and tries throughout the film to slip outside. The family always brings him back, lovingly to be sure, but inexorably. One feels the same eagerness in Cleo and Adela to escape the confines of the house. Late at night, after the young women have returned to their servants’ quarters, they mention feeling spied on, with Sofia chiding them if they leave the lights on at night. They exercise—charmingly only three toe-touches and three-sit-ups—by candlelight. When Adela and Cleo are sent on any outside errand, and especially on their day off, when they dash pell-mell down and across streets even at peril of being hit by cars. The young women rush to fill this brief free time, going to a restaurant, and on separate dates—Cleo to a hotel for a sexual tryst, which results in her becoming pregnant. She has so little chance to do, try, and experience life in a more measured way. When the family later spends New Year’s at a country hacienda, Cleo revels aloud at being outside in a place with a horizon and with the sounds and smells of the natural world, not the same as, but evoking, her native Oaxaca. We see the class strain in the casual entitlement of the family, how the children think nothing of dropping their wet coats on the floor when they enter the house for Cleo to pick up. When Cleo, clearing away the family’s snack dishes, is swept up in a comedy show that the family is watching one evening on the TV and lingers for a moment to laugh alongside them, she is immediately sent to bring the father some tea. Cleo and Adela carry heavy suitcases to and from the car and baskets of laundry up two flights of stairs to the roof where they wash seven people’s clothes by hand. On New Year’s Eve, when the family visits an uncle’s hacienda, we get a second glimpse of this “upstairs / downstairs” divide—the patrons in fine clothes drinking champagne from fluted glasses, while the help celebrates downstairs in work clothes, drinking pulque and mezcal from clay mugs. When a fire breaks out and everyone rushes to “help,” only the workers and children pour water on the blaze. The family laughs and continues to drink and sing. Although he, himself, is poor, the final word that Cleo’s jilting lover, Fermin, throws at her is “servant.” And yet there is also genuine affection between Cleo and the family she serves. The children respond to her as warmly they would to their mom. She sings Mixtec lullabies to them. She watches their squabbles, attuned to when the tension between the kids threatens to break out into something dangerous. Due to her social position, she cannot always intervene effectively, but she is more alert to the nuances of the family than the grandmother or the absent / distracted parents are. She tries her best to console the weaker members. The children initiate physical contact with her and tell her that they love her, without the sense of duty that accompanies similar gestures to their parents—especially their absent father, Antonio. When Cleo anxiously confesses her pregnancy to Sofia, worried that she will be dismissed, instead Sofia responds with compassion, telling her that of course she will be well-taken care of, and indeed Cleo is brought to see the family doctor immediately to check on her pregnancy. The relationships depicted between men and women are painful. Antonio is having an affair with a much younger woman as he hides behind the fiction that he is working in Quebec, which his wife soon realizes. Our first introduction to Antonio is of his hands on the wheel of his car, manipulating it just so, forward and back, to fit it into the cramped space of his garage, while at the same time smoking a cigarette and fiddling with the classical music on the radio. We can tell that he likes his world to be just so. Having given up on his marriage, he never turns his body towards Sofia, only away, his affections and attention elsewhere. Fermin, Cleo’s impregnator, spends part of their first tryst demonstrating a karate kata nude in their hotel room. His body is lean and hard. His nakedness is neither affectionate nor vulnerable, but rather menacing, as if to say, “Training is my world, anything that interferes with it will be smacked out of the way. Even naked, I could destroy you.” His body is not an instrument of love, but of violence. (It was interesting, too, that this movie chose to have full-frontal male nudity but no female nudity, which I welcomed.) This motif of barely restrained male violence recurs when Cleo tracks Fermin down later on the training field near the slum where he lives. After she approaches him, he again whips his training pole around her pregnant and vulnerable body, ki-i-ing and telling her that if she tracks him down again, he will beat her senseless. (It’s no surprise that he is recruited into a paramilitary gang, or that the last time we see him, he is menacing Cleo and Teresa with a gun during a riot which she is swept up in while shopping for a crib.) At the hacienda, we watch Cleo inadvertently witness a drunken relative hitting on Sofia. When Sofia rejects his advances, we fear molestation, but he staggers away, commenting that she isn’t that attractive anyway. Family practices, too, prepare the children for their gendered roles. The mother askes that Cleo not give her daughter dessert so she doesn’t get fat, yet the boys are allowed to eat freely. We watch the oldest son’s rage and cruelty with concern, as we sense him growing into damaged manhood. Fermin’s outdoor martial arts training scene is also key in that it contains the second airplane sighting and a metaphor for Cleo’s function in the family / movie. Professor Zovek, a guru of sorts, comes to give a pep talk to the male trainees. They, and the watching crowd, expect something mind-blowing. Instead, he blindfolds himself and stands in tree pose, immobile. When everyone becomes restless and skeptical, he challenges them to shut their eyes and try to do the same. The camera pans over a field of wobbling, falling people—except for Cleo, who stands in perfect immobility, pregnant, but deeply-rooted. Despite the various traumas and uncertainties that she endures, we feel a calm, strength in her. Sadly, or luckily, we aren’t fully clear which, Cleo loses her baby. Her water breaks when she is crib-hunting during a demonstration that becomes a riot. There is no escaping the ensuing traffic jam, and by the time she reaches the hospital, her baby has aspirated meconium and is born dead. She is plunged into a paralyzing depression that only lifts after she goes on a trip with Sofia and the children to the beach so that Antonio can remove his possessions from the family home without the children present. Sofia, never the most attentive parent, decides to go and check her tires before they return to D.F. the following morning, leaving Cleo, who doesn’t swim, alone with the children at the beach. Of course, the unruly children venture out too far. Cleo puts herself at great risk to wade out and gather them back. The mother returns just as she hauls them dripping onto the sand. As everyone embraces in relief, Cleo bursts into tears and confesses her guilt at not having wanted her baby. Unstated is her fear that her rejection of her pregnancy is why the baby died. She is held tightly by the family in a huge, forgiving, and reaffirming hug. In the closing scene of the movie, Cleo’s spirits seem restored as the family enters into the “new adventure” of life post-Antonio, with Sofia taking on different work, and all of the family members inhabiting other rooms than they had lived in before they left for the trip. The movie closes with the same airplane crossing the city skyline. What does the plane symbolize? Destiny? Life itself, moving quickly past? The social changes of modernity? The youngest son, we sense, is the author / director of the film, an old soul even as a child, speaking to Cleo of his dreams, in which he is always a grown up, navigating his way through hazards. The movie ends much more happily than I supposed. Upon learning that Antonio was leaving the family, I feared that Sofia wouldn’t have the resources to keep Adela and Cleo on and that she would have to return to her village a “burden” or a “failure.” I feared that Fermin would shoot Cleo, that Cleo would drown saving the children, or that one of the children would drown. But the movie avoided melodrama—its suffering was life-sized and stemmed from believable sources. Do not worry that I have exhausted the insights to be gained from this deeply satisfying film. Each detail seems carefully chosen to bring the time period and this particular family’s experiences to life. I look forward to noticing more and to plunging deeper into Cuarón’s vision in a second viewing.  Devon Balwit teaches in Portland, OR. She has six chapbooks and two collections out or forthcoming, among them: The Bow Must Bear the Brunt(Red Flag Poetry); We are Procession, Seismograph (Nixes Mate Books), and Motes at Play in the Halls of Light (Kelsay Books). Her individual poems can be found in The Cincinnati Review, The Carolina Quarterly, Fifth Wednesday, the Aeolian Harp Folio, Red Earth Review, The Fourth River, The Free State Review,Rattle, Red Paint Hil, The Inflectionist Review, and more. 12/2/2018 Editor's Remarks russellstreet CC

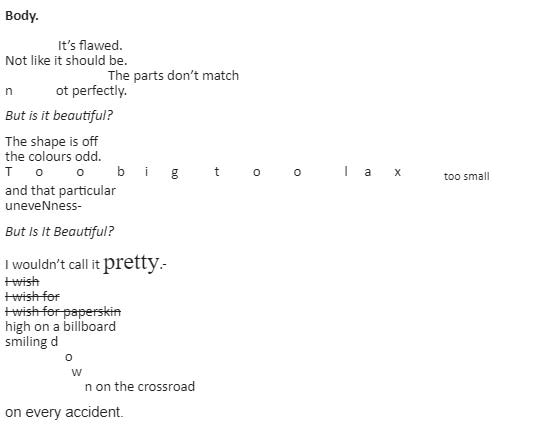

How is it that these words of ours are somehow able to hold us together? What impossible alchemy of elements mixes in our broken hearts? December often seems to smooth us over, like an ocean does a rock. But why would one need a reason to be so soft? There are reasons to be hard, to hide, to dig in. And there are, sometimes, reasons to reach out. How far can we extend? For how long? Who knows. The poems, stories and truths in this issue make me think it is important that we at least try to unlock the words that become trapped in us. Find the place where they run off our page and toward other hearts that are also on the outs. To know total disrepair and breakdown is to speak softly, when and where one can. Trauma creates a blank but something else in us finds a form and lives on despite a thousand, generously gifted deaths. We cobble together a patchwork beauty. We are so necessary it hurts. And hurting, that too is necessary. If we're lucky we live through the pain to tell our own story. We share a light born of a thousand wounds. From here to there, everything happens without warning. Love, forgiveness, grace, mercy, pain, laughter. Healing is the song, no matter the words. They find their time, come when they are called. We are called to be here for each other, it's that simple and that complicated. James Diaz Founding Editor Anti-Heroin Chic 12/2/2018 Poetry by Laurence Whitesomeday, I will love Laurence White after Ocean Vuong Laurence, I will not press you into this poem like a flower. You are beautiful, you have known how pages turn into hands. So quickly, and without warning. Hands with no body except the one above you. They will pin you to the bed as soon as they decide you are art. Laurence, I know you love the story of the woman who climbed outside of herself, but you don’t have to leave your body behind just because someone forgot you were inside it. A painting is never finished. Despite what they told you, your body is not artwork. You are not a painter. Put down the brush. Laurence please come home. You have been out too long searching for a version of yourself that does not exist. Come home and sit at your own table and eat. As much as they tried to make you, you are not a statue. Eat. There are people who want to feed you. Eat. There is a person inside you begging to love you. Eat. Listen, I know you never thought you would make it this far. That it never made sense to plan for the future, but today you saw the ocean and it made you smile. The Artist Has Come Home I come home only to set parts of myself in boxes. Every section of me too difficult to witness placed neatly inside. I cover my arms in satin (thread count stacked high enough for my scars to not show through) and put on my grandmother’s pearls. I touch my neck, the bruise the sad, hot girl made there has faded, but I still catch my hands moving over it when my mother peers at me from the corners of our home. Dad comes to my room to say he loves me, but lets mother cut up my heart and piece it into cookies for my sister’s bake sale. She has the prettiest soul they say about her. She knows how to give. The artist, I have come home. the one who says those funny things about our God and feels too deeply, I have stepped inside. Everyone senses something is wrong in me, the way I look down at the hardwood floors and cover my stomach in an attempt to contain. There is no danger in this tall clean house. They see no explanation. My motive, it is selfish, it is insane. I must not speak or I will scream the blood curdling scream. I am so angry all of the time. I have lopped off most sense of self to fit better in their church pews and dinner party chairs. I have lost so much mass as sacrifice. I peer down at myself and wonder what I would look like if I had never been asked to grow up here. I curl up in the kitchen as pure beings of abstracted light lumber through the domestic scene. I scream into my pillow or gawk at melting pots and pans. Mother’s touch has begun to burn me and I cannot understand the sound of her voice anymore, all it makes me think about is blood. It stains my sheets, dripping sticky & edible from my palid thighs were the self inflicted wounds reside. I am their founder, I admit I am proud, but do not tell that to my mother. She locks the door and stuffs her favorite daughter full of sweet nothings. Septic belly, I vomit fowl feelings into the trash can. I am ignored, politely. Everyone continues their small talk, I hear I laugh along, hands covered in stomach bile and spit. In the mornings I take my pills, swallow them down like a good girl, watching my family’s portrait. I can hear them clapping softly as I reach a more balanced state. Maybe one day I will become better at holding the proper pose, but you can always see the struggle in my face, my mother says, I never look at ease.  Laurence White (they/them) is a non-binary Kentucky born poet who lives in Santa Cruz, California. Laurence has published one thing in one book and is about to release their premier zine For, Ever. Laurence recently released a collaborative bedroom EP under the name Chaotic Futch. When Laurence is not speaking or listening, they are in silence or searching for its inexorable stillness. That is where you will find them. 12/2/2018 Sugar Lips by Ardyn HondaSugar Lips Remember your first date. His car broke down before you even got to the theater, hood billowing like your grandfather with his after dinner pipe. You call your mom to drive the rest of the way while adamantly refusing to look over at your date the entire trip there. You don’t remember if the movie was any good, you only remember the way your heart sunk hearing his racist comments and closing the door in his face when he leaned in for a kiss good night. Your palms are sweating, heart hammering as you push your back against the door and hear your father ask why you didn’t at least give him a hug. You think he’s angry but all you can think about is the sound of the closing door. You were fourteen and his name was Shay. Remember the first time you let someone touch you. He had dark hair and eyes that you could melt into. You both had an intro to creative writing class together at the local community college, and you brought brownies every Wednesday to impress him. He never ate them. Instead he invited you to come over to watch My Neighbor Totoro. He was your first kiss and when his hand wandered lower you didn’t want to say no and disappoint him. His tongue felt like an eel trying to drown you by seeking solace from the air in the warmth of your throat. You ate a granola bar and kissed him on the cheek when you left after his mother came in, furious. You were sixteen and his name was Mason. Remember your first girlfriend. You drove up to Bellevue, an hour long trek, every Friday to surprise her with a rose and sit in on her art classes. You held her hand and kissed her on New Years Eve with a glass of champagne at your parents house. You’d never been allowed to have alcohol before-- at least not with your parents. Your father didn’t spare you a second glance when she was over and berated you for letting her eat skittles out of the bowl when she had a head cold. You were seventeen and her name was Jasmine. Remember everyone in between. Those that took too much without asking, making the home of your body feel more like the abandoned house at the edge of the cul de sac with the overgrown lawn. Remember the wandering hands and nights spent holding yourself and wondering why you handed yourself out like candy on a Halloween night, complete with cobwebs hidden in every corner. Remember looking back at them through rose colored glasses obscured by one too many shots and playing your music louder to drown out your friends concerns. Remember that it wasn’t all bad, everything shaped you into the beautiful you that exists today. Only most of it was bad. Remember your last ex. Her smile lights up the room and you relax in the loud social setting, the passersby around you fading into an echo as you focus on her like a lifeline. You were told you didn’t deserve her. Your family loves her, even your father, and you understand why. She’s your best friend but you don’t realize it until you break up with her through text, only the staircase separating you. You were twenty one and her name is Ramona. You’re twenty two now and you have a date on Monday. This isn’t the first time you’ve asked out a guy but it’s the first time he’s said yes. It’s the first time you would swear butterflies made a home in your stomach and the thought of vomiting on his shoes seemed all too real a possibility. Your hands shake when you pull out your phone to exchange numbers. You bite your tongue to keep from apologizing. When it’s over, you can only hope it’s something that lasts. You’re twenty two and you’re not ready to say his name yet. Ardyn Honda is currently a senior at Western Washington University in Bellingham, Washington. They dabble in nonfiction, short stories, but their true love is poetry and focusing on what makes life art. 12/2/2018 Poetry by Steve PasseyFive Fights Every Night You think it’s Scars from fists Elbows and knees Sometimes even knives It ain’t like that It’s alcohol Fear and hate (All kinds) No money No money No money No money And Everyone Penned together With all the other Lesser lives Nothing to Burn I don’t even have a picture to set fire to We don’t have photographs now, just pictures, And we just erase them, so There is nothing to burn  Steve Passey is from Southern Alberta. He is the author of the short-fiction collection "Forty-Five Minutes of Unstoppable Rock" (Tortoise Books) and "The Coachella Madrigals" (Luminous Press) and many other individual things. He is a three-time Pushcart nominee, a one time Best of the Net nominee and is also part of the editorial collective at The Black Dog Review. Tweet to him @TheStevePassey. 12/2/2018 Body by Goldie Earnest  Goldie Earnest lives far away, in an ancient city, in a land of many broken empires. She has a degree. She puts her poems online. Her Mum worries about her when she reads them. The focuses of her literary works are the relationship between nature and humankind, the concept of borders, the struggle of fully accepting oneself, both body and mind. Her blog address is goldiearnest.wordpress.com and @earnest_goldie is where she tweets. 12/2/2018 any way the wind blows by Jordan Boyd Ernesto De Quesada CC any way the wind blows he’s just a poor boy from a poor family and I can’t remember his name at all just a few little gestures between dark and light the wink of a right eye the sour pucker of thin brown lips raised eyebrows as if question and a pint of Jack Daniels in left hand as he twists back my palm secures the half empty full bottle as if to say yes I search for the calm in cringe as you easy come easy go and yes I do know some of the words to Bohemian Rhapsody as you caught in a landslide no escape from reality slurring song in unison with the radio and a stranger the right side of his mouth a little higher when he winks whatever his name is deep wrinkles around his eyes from of all the nights we never knew each other the glass bottle back against my puckered smile singing the same words together as the air we breathe I see a silhouette of a man thunderbolt and lighting  Jordan Boyd is an artist and educator living in Oakland, California 12/2/2018 Poetry by Katrina K Guarascio Claire Cook44 CC

Ordinary Grief “How does one commemorate the ordinary?” ~Sherman Alexie You Don’t Have to Say You Love Me flowers are a start even if they are cut even if they too will die after all we do not want our grief to outlast its usefulness the way trinkets and mementos so often do grief will outlast the flowers but they will serve as a reminder the cycle continues there is always something changing in our hearts from decay a newness can arise with love forgiveness passing of time shells soften by the turn of tides diamonds eventually crumble to sand grief shouldn’t last forever take time commemorate this grief this ordinary this everyday but don’t ask it to remain like the most resilient of roses grief too will shed its pedals and lose its glamour grief will return to earth it will erode like fallen leafs like skin and bones like love and in time it will be forgotten For Amanda When I learned someone I love killed herself, the first thing I think is where I was when it happened. I think about the last thing I said to her and how many days ago I said it. I realize how trivial words are. The next thing I do is picture the scene as described. I can see it to the smallest detail, the sweat on her palm, the quiver of lips, and the dust on window ledge. I can clearly imagine the cat hair left on the carpet as the last thing you saw as you rested head to floor. Amanda, you were never much of a house cleaner. It’s not long before I start playing the what ifs, the untuned strings of what happened, what I should have said, where I should have been. Amanda, I did not answer the phone the last time you called. I didn’t stay for one more drink after your insistent invite. Amanda, I didn’t know your favorite color and I can’t remember the name of your cat. I didn’t know you spent your last birthday alone at a bar waiting for friends who never showed. But I remember the night we jumped the fence and walked through the graveyard passing a bottle between us. You taught me the name of each of the twelve moons and laughed at me when I forgot the lines to my favorite song. Amanda, The last time I saw you, you grabbed my arm and said thank you. Told me of the ten people you called this evening I was the only one who called back, I was the only one who showed up. I know what it’s like to feel that alone, to summon the courage to send a message only to receive no reply. I know the disappointment of misplaced loyalty. I, too, confuse friendships with propaganda and a kind smile for a kind heart. Amanda, I wasn’t there that night. I didn’t follow the crumbs, didn’t decode your hints, I wasn’t there to save you. But you should know, that was the only time. Because, now, every day I mouth the words I should have said. Every time I reach out I pull your body next to mine. I have been your champion, your savior, every time I close my eyes for the last 217 nights. But you aren’t around to see the sizes of my heart. You are gone and if you gave the foresight to wave your flag in my direction, I was looking the other way. Amanda, did no one tell you the definition of your name is “worthy of love?” Did no one tell you “you are loved?” Would it have mattered? Was your mind already made up? I don’t know if there is anything I could have done to truly make a difference, but I do know I would give anything to have answered that call, to hear you laugh at me again. to stay for one more drink. Katrina K Guarascio is a writer and educator living in Albuquerque, NM. She is seeking an audience for her ever growing surplus of poetic meanderings. She is grateful to anyone who reads her work and in awe of those willing to share it. She hates writing bios. 12/2/2018 Summer Desserts by Monique KluczykowskiSummer Desserts The rhubarb not as good as my mother’s—nor can I make her wine pudding—smooth and delicate from roughened hands with thick blue veins that threw a clot or many—erasure of recipes and faces. She knew some-- my daughter’s Ariel-red hair, my patient sister, I the anonymous portrait in a staged house stripped of souvenirs. Hospice is endless ministers and hams arriving hourly-- is your mother religious? How would I know, now. One brings a guitar, wants to sing—she liked music. The old hymns comfort and gut. My applesauce is not right either—she boiled and stirred special green apples from Indiana round and round with a wooden spoon smooth through a sieve, smooth as her face wearing makeup for the first time in that cold room in August.  Monique Kluczykowski is a first-generation immigrant who was born and raised in Germany. She has lived in Texas, Kentucky, and California, has worked as a band roadie, waitress, warehouse picker, and taught English for many years at Gainesville College in Georgia. She now makes her home in Iowa City. Her work has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize, and her most recent poems appear in Belletrist, Sierra Nevada Review, StepAway Magazine, and RabbleLit. Her most recent creative nonfiction is forthcoming in Blue Earth Review (2018 Flash CNF contest winner) and has been published in The Examined Life Journal. |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

April 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed