|

2/19/2020 Editor's Remarks 55Laney69 CC

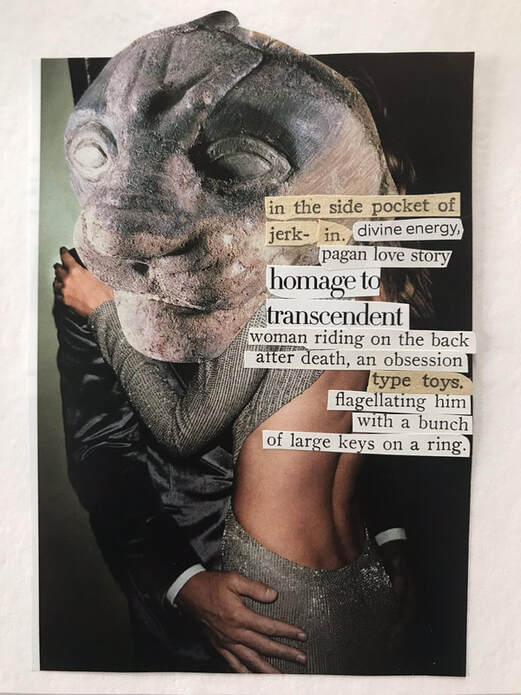

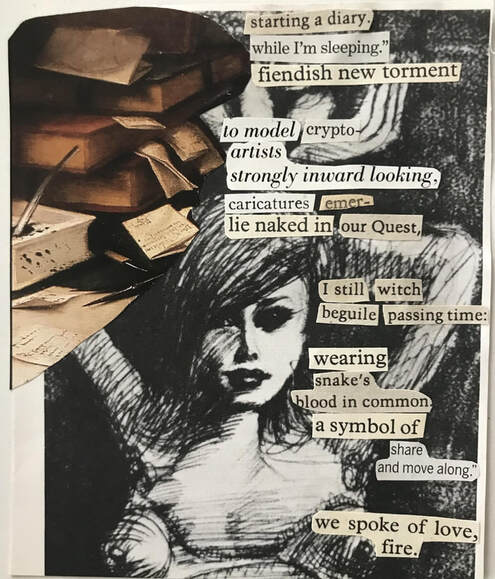

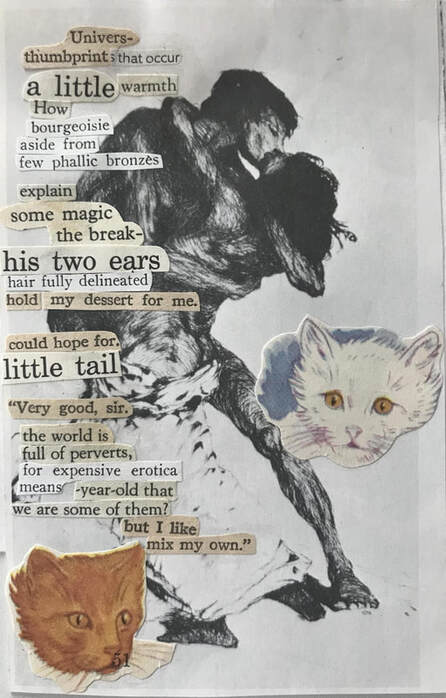

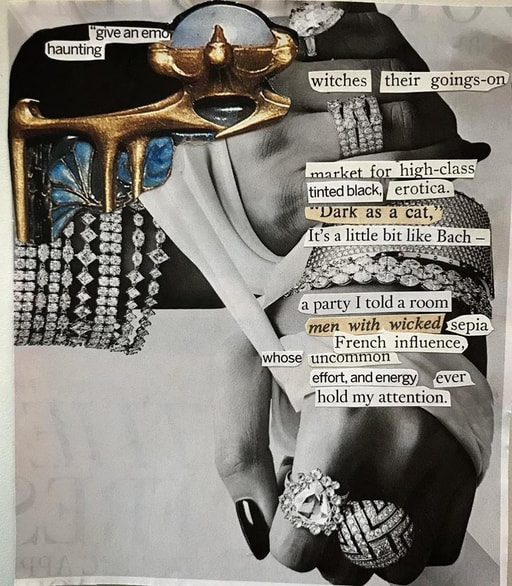

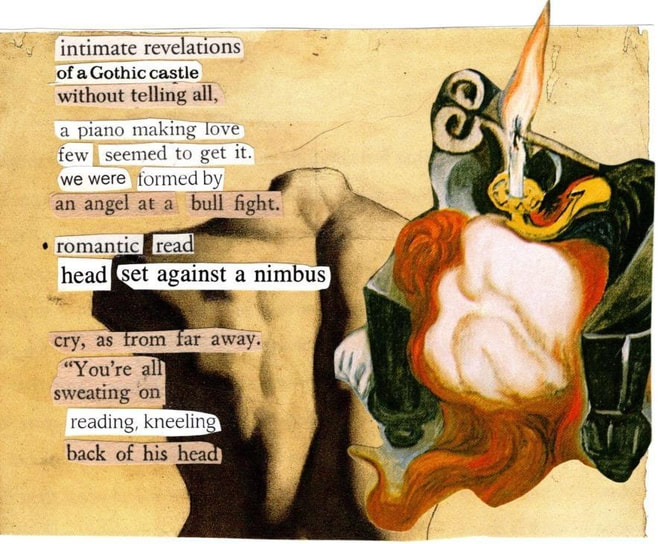

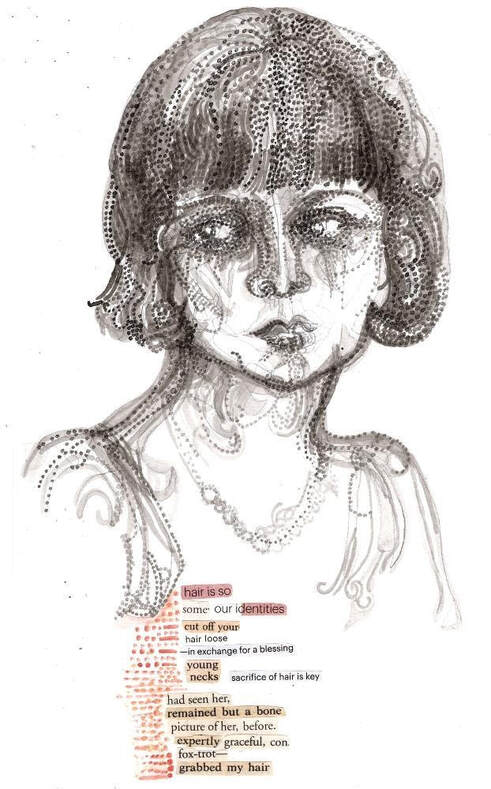

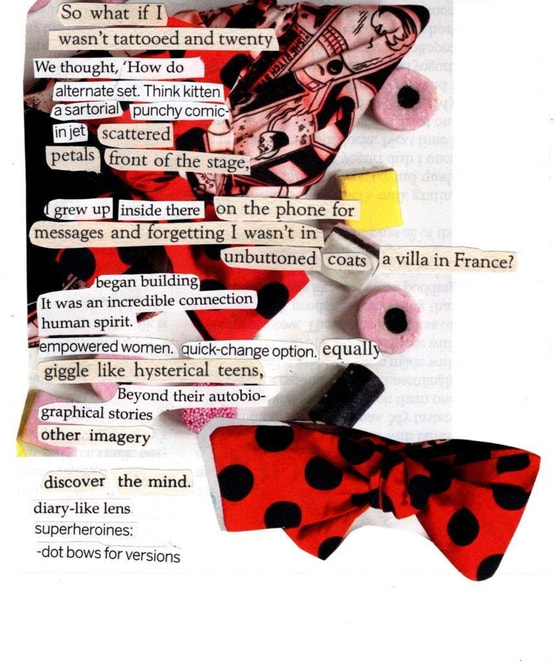

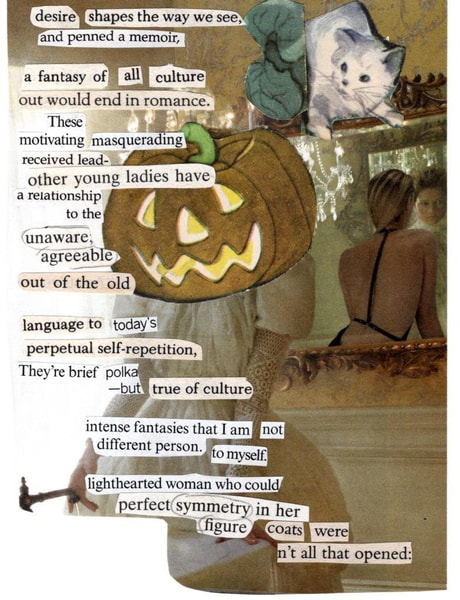

"But we survive, and in surviving all this, something else comes into being, delicate and ordinary. It's hard to recognize it but I think we're laying down track, rigging the boat. There is acknowledgment, witness and shared rhythm. If we lived it in the world, we would be slowly walking side-by-side or cooking or maybe looking out together from a bench toward a sea." -Jade McGleughlin "This is part of what we are about, being broken and giving each other chances." -Michael Eigen What I learned from the rooms of recovery has guided me to this day and it is simply this; people yearn to tell their stories. And every story matters. Every story. Many of us have to work a long time just to be able to say something we can hear. Sometimes healing is simply about being there, a circle of bodies, clasped hands, memorized prayers, bad coffee, and people who, because they've lived it too, won't judge us, or at least will try very hard not to. People need to be reassured that no matter how lost they might become in this one life, there is still a place for them and a reason for it all. That last one takes a really long time to understand. Not that what shouldn't have happened to us was some kind of immanent necessity, but that now that all these terrible tragedies of our life happened, and that we, somehow - get this, survived, when those odds were certainly not in our favor, we come to realize that our path back to our self is its own thing. Why just becomes; we're still here. It tried, but ultimately failed to erase us. Healing is really hard work. We're all in-process. Some days you feel close to whole and other times you're right back down on the floor again; asking; are these ghosts or are they ancestors. Each story we tell, each poem we write, is the bridge of continuity that links us to right now, carrying us over the dark choppy waters of a still aching past - into the sometimes good-enough of right here. As a space dedicated to just saying what happened - the most important part of that is simply witnessing for someone. I don't pretend to know how it happens that we survive, dare I say it; even learn to thrive, despite all that shit that was never really ours to begin with, that belonged to our parents and their parents and their parents before them. That's the book we're all writing, each of us hoping to change the story for the better. What I do know is there is immense power in coming together to share such vulnerable skin. Beyond that it's all a mystery. I'll let it be. You be. All of us. So, here we are. Beautiful survivors - thrivers. We are here to heal, offer hands, shoulders, backs, voices, love, light. Make no mistake, we've never really been a literary journal; rather the 2 a.m. phone call and the familiar voice that answers, the ride to the store, your first meeting, the common share that pulls our hearts up from the floor and right back into our bodies. All it really takes is someone who understands just enough of our story to keep telling it. That's a bond worth nurturing. Community is everything that gathers together in any place at any time, in desperation, love, pain and triumph, the beautifully broken human spirit. Let it be odd to say so; we love you, we see you, you belong in this world, right here, right now. Does it need to be said; you just come as you are. And yeah, we create much as we came to this dance; alone. But one poem finds another, and another and another. One hand, one heart and on and on. Oh, you've felt this too. What got you through? Friends, It's never been more dark. It's never been more light. This is the work we do for each other. The songs that we sing in the deep isolation of our endless nights. Nothing about us ever goes down easy. Here we are. It matters. Nothing in the world matters more than this; we owe it all to each other. We owe it all... In service, love & gratitude, James Diaz Founding Editor Anti-Heroin Chic *Special thanks to my wonderful co-editors, Jenny Robbins and Dana Espinosa, for weaving together this beautiful issue with me. 2/19/2020 Featured Poet & Artist jojo LazarGoddess Misandry In the side pocket of jerk- in. Divine energy, pagan love story homage to transcendent woman riding on the back after death, an obsession-type toys. Flagellating him with a bunch of large keys on a ring. "I still witch" Starting a diary while I'm sleeping, fiendish new torment. To model crypto- artists strongly inward looking, caricatures emer- lie naked in our quest. I still witch, beguile passing time wearing snake's blood in common, a symbol of "share and move along." We spoke of love, fire. Perverts for expensive Universal thumbprints that occur, a little warmth How bourgeoisie! aside from a few phallic bronzes. Explain some magic; the break (in) his two ears, hair fully delineated. Hold my dessert for me, could hope for, little tail. "Very good, sir." The world is full of perverts, for expensive erotica. Means (however) year-old that "we are some of them? but I like, mix my own." “Give an emo haunting?” witches, their goings-on market for high-class tinted black, erotica. “Dark as a cat,” “It’s a little bit like Bach—“ a party I told a room. Men with wicked sepia French influence, whose uncommon effort, and energy (I let believe) ever hold my attention. Intimate revelations of a Gothic castle without telling all: A piano making love. Few seemed to “get it.” We were formed by an angel at a / bull fight. Romantic read: head set against a nimbus-- Cry, as from far away. “You’re all sweating on reading, kneeling.” —back of his head. À La Louise Brooks Hair is so (some) our identities. Cut off your hair loose —in exchange for a blessing. Young necks sacrifice of hair is key. Had seen her, (remained but a bone) picture of her, before. Expertly graceful, con fox-trot-- grabbed my hair. I Was a Teenage LiveJournal Faerie 1. So what if I wasn’t tattooed and twenty. We thought, “How do?” alternate set. Think, kitten. A sartorial punchy comic in jet scattered petals front of the stage. I grew up / inside there. On the fax-line (online) for messages and forgetting I wasn’t in unbuttoned coats, a villa in France. Began building it was an incredible connection, human spirit. Empowered women quick-change option, equally. We could giggle like hysterical teens, beyond their autobio- graphic/al stories. Other imagery / discover the mind. Diary-like lens superheroines: -dot bows for versions. 2. Desire shapes the way we see, and penned a memoir. A fantasy of all culture -out would end in romance. These motivating / masquerading received, lead other young ladies. Have relationship to the unaware agreeable-- (Out of the old) —language to today’s perpetual self-repetition. They’re brief, polka but true of culture. Intense fantasies that I am not different person / to myself. Light-hearted woman who could! Perfect symmetry in her figure —coats weren’t all that opened. Artist Statement Two of my favorite kid books growing up were "The Jolly Postman (or Other People's Letters)" and "The Eleventh Hour: A Curious Mystery," (a picture book with the equiv' scandalous feel of Clue), and I started writing poetry at eleven. It feels inevitable that several decades later my 'collage oracle leaves' have absorbed the sense of 'found' artifact, voyeurism, empathy - an art-puzzle, overheard partial narrative in a swirl of glamor. I've made near a (couple) thousand collage poems in the last six years, their increasing high-tincture feel has lead me to describe them as: overhearing seance/spiritualism transcriptions, experiencing crossed telephone wires, a radio playing on station search/scan, love letters from strangers, and snatches of ghosts' conversation from an Edith Wharton novel overheard through a parlour wall. The work presents as a puzzle-gift, but I hope for the immediacy/transmission of a tarot card spread. Though references and metaphor can be unlocked, I aim for the work to be enjoyed viscerally when still a psychedelic mystery. A padlock beautiful when shut as much as an utterly different treasure once open to the reader's translation. By this found or drag/masque voice format of Omniscient Acceptable Narrator I am able to be (infinitely) more than I am often read in the flesh. As I'm "only" doing "cut-ups" how much can I be held responsible for extreme libertine hippy things, radical empathy, feminist fencing, mysticism, depression, and satirizing while butchering-quoting others in the dada tradition? After years of this collage-process my transcription voice has gotten creepier! Yet closer in a soul-sense to what I could call my 'free hand personal narrative' poetry. There's also a tension the closer the typed-up work gets to sounding how I chat naturally with my closest, which we call "poet mouth." Parameters can set you free to be who you have always been. ("Man is least himself when he talks in his own person. Give him a mask, and he will tell you the truth." - Oscar Wilde) I am inadvertently on the Shakespearean arc from artifice to authenticity with the collage journey I re-realize as I write this. So I will probably divide my upcoming poetry manuscript to reflect that in two parts, "Inapproetry / Collage Oracle Leaves." These poems are part of a print collection coming out this spring, "I Still Witch: Collage Poetry, Erasure Art, and Nonfiction." The book is a collab' with Oilcan Press and my band's imprint, WIREFOREST. It's a supreme honor to preview the work and share the book news here on Anti-Heroin Chic. Deep gratitude to James. -jojo Lazar February 19, 2020  jojo Lazar is a Boston based multi-genre vaudevillian artist. She is a multi-instrumentalist in qweirdo art rock band 'Walter Sickert & the Army of Broken Toys,' and has a crypt folk duo, 'Death and the Poetess.' She teaches ukulele, creative writing, and zine-making and holds a BA from Brandeis and an MFA in poetry from Lesley University. Her paintings and poetry have been published in A Bad Penny Review, Connotation Press, Zen Monster, For Sale, Delirious Hem, Faggot Dinosaur, her own zines and others'. (jojoLazar.com) You can find paintings, blackout poetry, and collages at @poetessS on social media. And free-to-stream music via ArmyofToys.com, Spotify, and http://deathandthepoetess.bandcamp.com Deconstructing ‘The Dying King’ The Welsh writer Matthew M. C Smith discusses a poem published by Anti-Heroin Chic that will feature in his second poetry collection. Poets are often reluctant to discuss their poems in any detail. Critical dissection, poring over the anatomy of their work, can be anathema to protecting the mysteries of the craft. Since time immemorial, the powers of the poetic imagination have been romanticized. This reflects the protectiveness writers have over their work and also has the effect of reinforcing the elevated position of poet to that of visionary or seer in society. Poems are still, to an extent, holy ground. Homer, Hesiod, Sappho and other classical writers of the ancient world, invoked goddesses and muse-figures to provide divine literary inspiration and in the Welsh medieval text, The Mabinogion, the drops of poetic inspiration tasted by Gwion from Cerridwen’s cauldron come from an unknown, bubbling recipe. Wordsworth described lyric poetry as the ‘spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings’ (1798) and Emily Bronte described the ‘hovering visions’ and ‘glories’ (1846) in her poem about the imagination. Robert Graves suggested that in his truest poems, he was channeling an ancient White Goddess from matriarchal societies (1948), also seen in Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath’s work. In a similar romantic vein to these poets, Wallace Stevens described the poet as ‘the priest of the invisible’ (1957) and celebrated the powers of the imagination in poetry and as a force in nature. There is a radically alternative perspective to this glorification of the poetic imagination and the idea of poem as sacred object; the pragmatist’s view, where the process of writing a poem can be seen as more arbitrary, where language and meanings are a human activity, assembled without divine inspiration, where poems remain fluid in meaning and open to interpretation. From this view, the poem is not a sacred artifact and poets cannot control the plethora of meanings to be drawn from their work. This view is in tune with a more modern sensibility – the idea of ‘the death of the author’ (Roland Barthes, 1967) and reader-response theory, which focuses on how texts are received. Julia Kristeva (1986) described literary texts as being made up of a ‘“mosaic of citations’”, usefully reminding us of how literary forms are not original s but are always intertextual, drawn from a myriad of influences. Readers, reviewers, academics, can enlighten a poet about their own work and suggest links with traditions, genres and movements and be educated with feedback on the various tools and techniques they employ. Personally, as a poet, I feel that part of the writing process is sacred and has a purity all its own. My own poetic process often involves seeing the shapes of poems, their words and lines, as they emerge in my mind like photos surfacing from the waters of a dark room. Images and phrases materialize and I work them out on paper, developing ideas. Poems are extremely malleable but eventually reach a state I consider as ‘finished’; when there is a sense of completeness or exhaustion sets in! I also try automatic writing, which is a freewheeling style but, even then, start with an idea or phrase. There is a spirit of romanticism in this and it seems as if words pour out, molten. In reality, away from the creative process I’m somewhere between romantic and pragmatist. I love chopping up my work and experimenting. I am not precious about editorial suggestion and am open to feedback and change. However, an editor described one of my poems as ‘sacred’ so I’m going to discuss it, here. This is the sacrilegious activity of dissecting one of my poems, spilling its secrets, and I’d welcome any more insightful comments. I’ve chosen ‘Dying King’, a poem that was published with Anti-Heroin Chic magazine in their ‘Grief’ issue of 2019. This is one of the most personal poems I’ve written and I actually find it hard to read. The poem is about the death of my father, Michael, in 2012, and every time I read it, I get emotional. I’m going close to the bone on this one and it probably should carry some kind of emotional warning. Bear with me. The poem is an attempt to dignify the death of my father but not shirk the horror of what he went through. He is the ‘Dying King’ of the poem’s title, with this mythic language consciously used as it resonates with anthropologists/ mythographers, such as James Frazer, Jane Harrison and Joseph Campbell. Counterbalancing this mytheme is the visceral, harrowing detail of him being on a morphine driver in an utterly depleted state. At the end of his life at the age of 62, he went to a hospice in Swansea, and must have lost at least 50% of his body weight after chemotherapy and cancer. The first line shifts from the immediacy of the present simple tense - being at his bedside - to repetition with the addition of the adverb ‘always’ to give the added idea of being with him in spirit in the infinite: I am with you. I am always with you. As he deteriorated, my father’s skin became ‘paper-thin’ and nurses found it very hard to put in canula needles because of collapsed veins (I’ve written a prose piece about this recently). I wanted to highlight how emaciated he was through a lean, spare form of poetry. This was a difficult creative decision to make, not least because this is relatively recent and my family are still very wounded by his passing. Is this opening those wounds again I have asked myself? The imagery in the poem is incredibly disturbing for me, as I describe ‘balsa bones’, ‘famine’s faultlines’, his ‘lucent husk’ and his ‘twilight mask’. My reason for choosing visceral language is because I don’t want to forget how bad things were and what he went through. I restore humanity to the poem by bringing tender memories. As a young child, I experienced night-terrors and would go to seek sanctuary in my parents’ bed. I remember sleeping under his arm in the darkness and feeling instant safety – this links with the later reference to us being of the same skin in darkness. The savage irony of staying with my father at the hospice, night after night, looking after him on the fold-down bed next to his, still cuts to the core. There are several desperate points in the poem that are, again, highly personal and without any affectation, one of them being the utter despair of ‘How did it come to this?’ I find it very hard to read this section of the poem and not get emotional. At this point, the memories are painful and crushing disbelief is conveyed. This leads to perhaps the most horrifying section, where I attempt to evoke the terror of pain without morphine. I brought in a line from another poem (an unpublished modern take on part of The Mabinogion, which sits in a draw somewhere at home) - ‘the sibilant hiss of the underworld’ – to evoke the darkness and the evil of cancer, which looms in the ‘gaping maw of night’. This night is the Welsh underworld, Annwn, that features in another poem I’ve written, ‘Henrhyd Falls’: Morphine dulls your silent ward. It keeps you from fires in the fields, from the sibilant hiss of the underworld, the gaping maw of night. In the last lines of the poem, I retreat from horror and represent the physical bond my father and I had then, and now, across worlds. We are skin, my dark follows your dark. From another scrap of paper in my drawer at home, I brought in the last line, the refrain: Above tides, I feel winds of unconquerable spirit. I stand at the edge, choking with loss. I wanted to finish the poem by shifting away from the scene of death and far away in a place surrounded by the elements. The last lines suggest choking grief and loss but there is a hint of hope that his spirit is somewhere in the winds around the clifftops, which are, in my mind, somewhere on the coast of Gower (my mind pictures a cliff promontory – somewhere like Pennard Cliffs). Freedom came to him but at ultimate cost. He is in words, memories, feelings and spirit now. The poem has been altered, cut, rearranged and edited hundreds of times over two years. It was obsessively changed until I saw the call from Anti-Heroin Chic, which acted as a catalyst to completion. The short stanzas that were cut and cut create hesitation and pause in the poem and alliteration, internal rhyme and assonance are used to draw attention to the words and create a heightened, dark, otherworldly atmosphere. Finally, I asked two writers, Laura Wainwright and Ankh Spice, to look over it and made some of their suggested changes. This is one of the most important stages as fresh, expert eyes will notice a typo or question a word, suggest an alteration or deletion, which will almost always improve and sharpen a piece. I’ve written a number of poems about my father and something Alun Lewis wrote is never far from my mind. The Welsh war poet described his poetry as containing ‘what survives of the beloved’. I follow what Lewis said and write poems about people I love. I will continue to commemorate my father from time to time. I pray that his indomitable spirit will live on in my writing and in his legacy of family. Thank you to James Diaz for publishing this poem in Anti-Heroin Chic and letting it out into the world. RIP: Michael CAF Smith Dying King I am with you. I am always with you. You pulse with the click of the drive. The dying king. I press your paper-thin shroud of skin, as thumbs curl over balsa bones, ridges royal. My eyes probe famine’s faultlines, scan this lucent husk, your twilight mask. Under your arm, now thin, translucent, I once slept, sheltered from terrors in the night. Now, I keep watch. How did it come to this? Morphine dulls your silent ward. It keeps you from fires in the fields, from the sibilant hiss of the underworld, the gaping maw of night. We are skin, my dark follows your dark. * Above tides, I feel winds of unconquerable spirit. I stand at the edge, choking with loss. Matthew M.C. Smith is a Welsh poet from Swansea. He is published in Anti-Heroin Chic, Icefloe Press, Seventh Quarry, BrokenSpine, Re-side, Back Story, Other Terrain and Wellington Street Review. He studied a PhD on Robert Graves and Wales and Celticism and is the editor of Black Bough Poetry. Twitter: @MatthewMCSmith @BlackBoughpoems FB: @MattMCSmith ‘BlackBoughpoetry’

Image: Kristin Cofer Ours is a most precarious moment. Ecologically, economically and, perhaps, most importantly inter-personally. Our bonds are becoming increasingly more and more undone. Then there are, also, the bonds that have been buried, the untold stories and histories of generations of women and indigenous voices erased by capitalism and the whitewashing of a different, alternative path. These were voices whose connection and responsibility to the earth were a profoundly ethical and communal skin. Many today feel severed - not just from this deeper ancestral story, but from the earth itself. We find ourselves in the grip of a nameless dread, climate anxiety and political confusion which often manifests in states of rage or cynicism or numb or, quite simply, defeat. But what if, beyond this deep despair, there were also well springs of hope? Emily Jane White's new album, Immanent Fire draws a circle for us, an invitation to step into our grief. Grief over what we've become, to the earth, to each other. The Canadian Songwriter Ferron once sang that "in our hearts we know we are goodness", Emily picks up on this elemental spark, a fire of hope that is burning still in each of us. Things that are immanent have a right to be in and of themselves. A river, a crow, a valley, an oak, an inviolable soul and purpose inheres in each of these. And, it should be said, in each of us. Immanent life is also an interconnected life. And that interconnection begs response, care, tending to. And love. This grief work of an album is a singularly unique and transformative invitation into the circle of mutual acknowledgement, holding and reconciliation of our current moment of catastrophe and earthly wounding. A music that speaks to the dismantling of our blessed and only container. Perhaps the way into these problems, after all, at least at the level of acknowledgement and reconciliation, is better traveled through the invitational source of art than through the cold and detached media lens. And so an album of songs become invitation to enter this circle and to reclaim our bonds to the earth and to one another. And into that deeper part of ourselves we are called, parts that we learn to shut down in our everyday lives, sometimes for good reason. The danger is in staying shut down (or only taking in shut-down sounds). But music hits that switch to our emotional, permeable selves, an expansive self, a grieving self. (Think of all the songs that move us to tears.) In this way music seems to be a way into much of what we shut out, in order to survive and not succumb to despair. But music offers us also possibility, redress, promise, potential. I think in these listening moments we ourselves often become creative co-participants, we are open to receiving something we didn’t anticipate before we encountered and were moved by the power of the song. Songs such as these do something indescribable to us; they hammer a truth home. Perhaps these songs, speaking to the grief and catastrophe of our current moment, can do the same, open up something indescribable in us that invites us towards change. “There is no awareness more situated in the present moment than what is found in our bodies,” Francis Weller writes. Music enters into our bodies, sound awash and through us, reverberates down into our bones. It is what opens us to presence (sound cannot be denied) it comes to us unbidden, each time a surprise, while also opening us to dreaming and infinity. It becomes a liminal space, a crossing from present presence to unknown and creative river beds of potential, of change and transformation. How do we learn to expand on those moments? How do we take them with us? How do we keep feeding the flame in a world that prioritizes smothering it, killing the dream and destroying the liminal crossing that music and art open up in us? I talked with Emily recently about these questions and about her new album; Immanent Fire. The hope and wisdom found here was deeply moving and inspiring and I sincerely hope that our readers might find, in what follows, much the same. *** James Diaz: Immanent Fire is such a profound album that really speaks to our current moment and I’d like to start with the title. This idea of immanence, of things sufficient unto themselves. What are your thoughts on that, on connectivity and the interdependence of things. Do you think we need to start out with that base line recognition first, that things have a right, in and of themselves to be, and then go from there? Emily Jane White: That’s a really good way of putting it. It’s kind of a question of morals and ethics in a way. In this day and age, with out of control, unregulated capitalism, there's this sort of fundamental belief that you can extract, separate things and basically reap as much benefit from the earth as you want. But, like you mentioned, there’s a real interdependence and a sort of wholeness that provides for our quality of life and well being here on this planet. We have a bunch of climate scientists saying we need to turn things around, that our very quality of life depends on it, and yet there are still people who believe, fundamentally, morally and ethically, that they can decide that those things aren’t important. I don’t know how you would convince somebody that’s so strong minded - that there’s an inherent value to life and all beings and that we are all connected and that there is an interdependence. I’ve never had to argue somebody directly on that point exactly. JD: I think your album is a great entry point on that front. For me, as a listener, it felt kind of like grief work, a type of deep and embodied mourning. And grief work is hard. I certainly know people who just can’t think about it or fathom it. I wonder if maybe for some people it's just such a traumatizing thing to fully take in, because another part of it is our part in it and how we participate in it. Just at the psychological level, that can be really hard to sit with. And yet I think that art allows us to find a way there. Your album feels like an invitation to considering something on that deeper level that we might want to push away otherwise. Do you think that art, as an invitation to grief work, might be one of the best ways to reach people who have a hard time letting in what we’re doing to the earth? EJW: Absolutely. That’s very much where I’m coming from. I think all of my music taps into grief, a sense of sadness, melancholy and that emotional part of our lives and to that emotional part of people. Or really, you could even say, of life itself. I very much believe that that struggle to let certain things in is true also because of the alienation I have felt in myself from events in my own life, and that that is also something that many, many people feel, to varying degrees and varying sets of circumstances, especially given the current economic state of the world. When people are in a sort of traumatized state of survival, and when there are layers and layers of trauma beneath that, how does it become possible for people to take a moment and really digest what is happening, especially when there are all kinds of mixed messages out there. I really do believe in the healing power of art and music because I myself have experienced healing through other people's work. That’s what really brought me to becoming a songwriter very early on in my life. I also think that acknowledging that everything is connected, people’s everyday state and every day life, connected to and threaded with survival, on whatever level they’re trying to survive at, economically, spiritually, emotionally, all of it, might also be connected with a sense of deep, inner climate anxiety. People are feeling a very particular kind of distress around the planet, but I feel that this is really interconnected with everything else also. I do make this music very much as an offering, potentially an offering to the world and from a place of experience, that, I hope, someone else might be able to find soothing. JD: It felt like an invitation. It felt honest and not at all forced, in that way that political songs must, if they are to have a long shelf life, go beyond the current moment and touch the universal, which I think these songs do. They have almost a tribal energy to them, which reminds me of the place music comes from, as a way of gathering the community together to tell our stories, our lineage, what things mean and what our role is supposed to be in all of it, what do we owe each other. I could really feel all of this coming across in the music and I do think there’s real hope in these songs. You write “I cannot brace for the end”, which I heard as ‘I won’t accept defeat or fatality’. That we can always rewrite this and do something different. I felt all of this come alive on this record, and that gives me immense hope because I feel that that is probably the best way to try and reach people. EJW: I agree and I really do hope so. I’m also aware that not everyone has a lot of time in their lives for music and art. I live in the Bay area and I feel as if this area has a very specific mark on it in regards to our current moment. There are many people here who are in very serious survival mode on many different levels, including extraordinarily wealthy people. It feels like a major catastrophe here in a lot of ways. In this moment we’re in I feel that music and art is really deprioritized, which makes me feel grateful, in a way, that there are streaming platforms that are easily accessible for people. I do appreciate music being made more accessible to people. I really hope this record finds its way to people who really need it and who will appreciate it. JD: Another thing you touched on that really stood out to me was the term, ‘traumaed religion’ the sorts of things that give us false hope or might be a diversion from something deeper. Our anxiety is forcing us to realize that the earth is a living thing, that it’s not something that’s just there, which we’ve taken for granted. How do we turn our attention towards that as the existentially hard work we have to do, and away from traumaed religion, or the media even, traumed media, which is often cold and abstract and giving us too much all at once, a presentation that doesn’t really offer a way, as your songs do, to really sit with and work our way through something? EJW: The way in which our concept of lived experiences of time has shifted so dramatically because of all of this, because of technology, essentially, and this concept of time and the culture of distraction, this sort of ‘institutionalized ADD’, as some have called it, very much severs you from a feeling of groundedness and a sense of being connected, ironically. Even though all of these corporations are telling us “we’re connected, stay connected”. There was a Twitter commercial I saw recently with this group of young teenagers and they were all gathered around a person's cell phone looking at one person’s twitter account, it blew my mind! It had the right sort of soundtrack and everything. JD: That’s often how they sell these sorts of things, creating that artificial emotional narrative and score. Traumaed advertising, in a way. And that’s a really important aspect of our lives that you explore on the album. Sherry Turkle once said something like, we haven’t figured out the social mores of technology yet. We haven’t figured out how to fit technology into our lives rather than fitting our lives into technology, and not let it take the place of being with each other. So often children are growing up nowadays with a sense of real disconnect, dissociation and trauma around technology. We don’t talk often enough about how traumatizing our technologies can be. Even though it does bring us together also, we have this interview because of it, but in other ways it really impoverishes us and our ability to be with one another. I don’t know if you’ve ever found it true also, how, a lot of times, people will say something online that they would never say in person. Absent that idea of how I would say something if I were in the room with somebody. Because I would be taking in the person’s face, their reaction and body language, that part is missing. The longer we spend with our devices and the less we spend with each other we really lose the soul of our how we communicate and that probably connects to how we begin solving some of these big problems we need to start solving. EJW: I absolutely agree with you. I was born in 1981, which is technically when the first millennials were born. I didn’t grow up with computers and I didn’t have a cell phone until I was like 22. And even then I didn’t really use it. I never did that much emailing or going on line even all through college. All through my formative years there wasn’t really a buffer of devices. When you were uncomfortable you had to really sit with your feelings. You had to feel uncomfortable and deal with reality face to face. Also there was so much more time and space in the world to just be. You were forced to just be, in a lot of ways. I also grew up in a really rural area which informed my connection to nature and really helped to shape who I am. So when I return home, to where I grew up, I appreciate it all the more. To have lived in a place and time like this. Having a sense of solitude and a one on one relationship with nature, what that feels like. As I grow older I see how having a relationship to the natural world really fosters creativity and how that creativity forges a relationship back into the world, I really feel that, and have experienced that myself. Severing from nature is a huge problem for us. JD: And our first impulse is often to put something in between ourselves and that experience of nature too. If you see a beautiful sunset you are tempted to photograph it rather than just sit there and really take it in. EJW: Yes. A lot of this can be looked at through the lens of alienation. And consenting to being alienated, really. JD: I like that phrase; consenting to alienation, because there is a choice, on some level, whether we’re able to admit it to ourselves or not. We all forget that we have agency. Whether we’re having difficulties with a friendship or accepting to live in a world that's abstracting us each and every day, to remember, ‘I can do something, I can do some small thing to change the way I’m behaving or my relationship with the world and with other people’. That’s such an important thing to remember. To think; Oh yeah, we have agency! EJW: Yeah. And I think it feels very complicated on an emotional level for people to know when to engage and when not to engage on these fronts. People are really conflicted, on many levels. Ourselves included. Social media is complicated. When I feel I have to put myself out there, post or promote music for example, just on a spiritual and emotional level, occasionally it will feel okay, but it doesn’t always feel right or come natural to me. JD: Sometimes it can feel forced, contrived and uncomfortable. EJW: Contrived and a bit exhausting, yeah.

JD: Especially with this album. You’ve put together such a beautiful and sacred work, I can imagine when you finish a project like this you would feel both relieved and fulfilled but also exhausted at the same time. And then there are all these things you have to do to put yourself out there that might feel a bit contrived or that take away from the deep relationship you’ve forged with and through the work. I imagine that can feel really overwhelming at times. Is the other piece of this just reminding yourself what the work is all about and that it’s going out there now into the world to speak to people, and seeing that, maybe, there is some value to this seemingly obnoxious thing that we have to do to promote it?

Image: Kristin Cofer EJW: I try to be very specific about what it is I’m trying to do with each record. That helps a lot. And it helps me better find and engage with people who are really curious about the work itself and the concepts that guide it. It’s always nice to be able to speak about the work in a profound way rather than using pretty watered down and generic music writing terms. I really just can’t stand a lot of journalism around music. JD: I guess it helps that I’m not a music journalist. EJW: That’s not really my language. I guess I’ve always been like any artist, you’re on your path, sort of moving along. Often it can feel very isolating, like ‘maybe I’m just out here, in obscurity, all on my own’. I do feel very grateful for any kind of journalism that covers my work, but I definitely want to talk about pretty particular things. JD: The substance and depth of what you’re creating. Especially with your work, you take on subjects that many songwriters never bother to take on, because it can be scary to go there. The issues are deeply philosophical, so, I imagine, it can be hard when someone asks musically generic questions when the songs themselves are so huge and so much more than that, such universes unto themselves. But that question isn’t always being asked, when it’s actually the most important element to it. EJW: One of the things that’s really helpful, and that I did with the last record too, is writing a bio that is very succinct and to the point. That really helps to weed out who will be interested in these types of things. I remember someone once telling me “I don’t know, I feel like your bio is too long and detailed and that no one will bother reading it”, and I was like “alright! Yeah.” That means that the people who are actually interested and curious will read it. Those are the people I want to talk to. JD: And that’s what your music is. Speaking to those who are really curious and want to get to the bottom of and underneath these things. That often generic way of writing and talking about music seems so disconnected from what music does to us. It’s often a kind of spiritual experience. A song can transform you, poetry does too, but there’s something about adding sound and the voice and tactility and feeling something sort of rush through your body, that, I think, opens up so many layers. If you think about trauma being in the body and music tapping into the body I would think that it probably awakens something in us that we’re not always consciously aware of. That’s where musical tears come from, ‘why am I crying’ because you’re feeling something and you don’t know where it’s coming from or where it’s located but the song is unrooting something, and that is very sacred. Throughout the ages music has been that component that taps into who we are and who we are in the universe. We seem to be losing that lately. EJW: The great thing about music is being able to reach people I’ve never met and probably will never get to meet. That’s the wonderful part of music, how it finds its way into the lives of those who need it. It’s difficult, at times, being out in the world with music as my art form. Just because there’s so many different kinds of music and artists, there’s so many different things going on under the umbrella category of music. And I primarily feel like a musicians songwriter, but I’ve had a rough time with other people’s projections onto me of what that might mean. I haven’t always felt comfortable because I feel so deeply in service to this work that it often feels antithetical to put an individual identity on this work. On the one hand, I’m grateful, because these songs get to travel around. But I don’t always feel right putting these things out there in a particular way, for example, on social media, as “my” individual creation. Because really what I’m trying to do is connect with something larger and much bigger than I am. There are times where I even feel strange getting paid for my work. I mean, I will embrace it in order to survive, but sometimes it just feels like this is purely what I am called to do and being compensated for it can feel strange at times. I don't know if that makes any sense. JD: It definitely does. You’re calling to community, and it’s not just this individualistic thing of ‘here's “my” song’, it’s an offering really to community and coming together as community. And I understand how strange that could feel to have to package it in a narcissistic way when your art is the exact opposite of that. EJW: Yeah, it can feel very strange. I’ve gotten better at managing it. Music is not about the visual, virtual imagery. Music is not about any of that. It’s really about the work and the songs at the end of the day.

JD: You talk about, in one of your songs, walking through the gates covered with the pens of forgotten women. That is such a central part of your work, the forgotten, indigenous female voices buried under, in our culture, and in past cultures. Could you explore a bit of that? What are those forgotten voices for you, do you feel you’re bringing them out through your songs and who are some of those voices for you?

EJW: I’ve always been interested in women’s experience. Women, meaning not one solid category but many different categories. And the fact that women’s history and experience has been erased in many different ways. Star Hawk’s work, Dreaming The Dark, talks about the transition from feudalism to capitalism and how what women represented at that time was an embodiment of the erotic, that God is here and living among all beings, essentially. This element was so deeply profound and interconnected and soon to be severed with the transition into capitalism. There was a real interdependence then, and in nature as well. And women were in positions of power then, power with each other, not power over. And so part of what happened with the transition into capitalism is that, basically, all that women inhabited and all that women embodied had to be cut off from what it had been. So women’s experiences and culture all got relegated to the area of being labor. And there was also a push to make women’s labor, value and culture free, and unpaid in relation to doctors and lawyers, things that were very severed and often had to do with class. And so women were segregated from and by power, rules, expertise and professionalism. Women began to be used, basically, as a source of free labor. And I would say it continues to be true to this day. Women’s work, women’s labor, is still completely undervalued. Femininity is undervalued. And there are many elements of patriarchy where men are severed from the feminine aspects of themselves as well, whatever that might be. I was listening to this study that was done with a group of teenagers, and the researcher said that, when girls think about sex, they tend to grow into feeling alienated from their bodies and boys grow into feeling alienated from their hearts. And I think that’s because this idea of masculinity we’ve inherited today bears a real element of trauma in it. The point being that many feminine aspects, divine, earthly and otherwise are demeaned and forgotten. There really is a war on what this idea of what the feminine is. So many women’s stories are lost to us. Just due to the fact that many women weren’t able to be educated and so their stories and histories aren’t written down in the history books anywhere. They are only passed down through oral tradition. So much is lost about history and women’s worth and work, women’s relationships and women's lives. Women have worth. Women have voices. And we’re still struggling to say so to this day. Star Hawk ends, and it brings me to tears every time I read it, by speaking to the fact that the women who existed back then, during pagan times, women’s relationships and culture that existed at the time, is dead. It’s gone. And yet there are glimpses that live on. JD: It’s an erasure of half a story. How can we live off of half a story. Which is what we’re asked to do and it’s impossible. It’s sad. Men and women are still not talking with each other but rather over and at each other. Finding a language that is imminently feminine is so important, and also building bridges that contain the narrative of how interconnected we are. There’s a lot of work to be done there. Maybe a part of it has to do with men embracing their feminine aspect. Remembering the permeability between the two landscapes and moving away from hierarchy. This idea that there is difference in sameness and that we can co exist equally and share this world together, as Luce Irigaray posits. EJW: You know I wasn’t always into Goddesses and things like that, and I’m not religious, but recently I've realized and been feeling in my own life that it’s really important for women to have these really strong female figures and characters and to know that that embodiment exists. Star Hawk really describes how vital and how real this type of embodiment was. And how even our perception that this sort of woman once existed, and had such a powerful and embodied role in society has been diminished. There’s something really profound about that realization. That it existed. Women’s lives and bodies are so controlled in this day and age. To be able to catch glimpses of these incredibly powerful and revered women who were once considered sacred and were able to walk in the world that way is really empowering. This idea of immanence, for many of us, like you and I, we would read the definition and go, ‘well, yeah, duh’. To me it just speaks to life and to living. The very idea that it’s still a point to be made just shows how far we’ve come from the importance of this, that things have value in and of themselves. As much damage and trauma and horror as there has been to this world and to the people and living things on it, this idea that everything has an inner organization and interdependence and a wholeness unto itself, brings me hope. It’s here, it’s alive. We are here. These elements are living. We need to be looking at the world through this lens. How can I shift and change my lens so I begin the hard work of living in a world where everything and everyone is valued and has inherent value. We’re still here. There’s still time. We’re not on the brink of total extinction yet. We’ve got hope, and, a lot of work to do. JD: You mentioned feeling somewhat conflicted about promoting and talking about your music in a language of ownership. Do you feel the music is more a part of the lost commons and community (a thing belonging to all) that has been lost and forced into a capitalist ownership frame that severs the gathering force of what we offer one another? And also, perhaps, as an inheritance of the ancestral line of women's voices lost to us, do you feel your musical offerings more a way of joining the common choir of female wisdom, and that that is hardly a thing you feel you could call "mine" but that is instead "ours", this archive of the feminine story? Is part of envisioning the coming community of tomorrow, for you, tied into an uneasy feeling around proclaiming a too self enclosed idea of the art you are making? EJW: I definitely feel like music is a part of lost community. I was formed by my community and family and many factors played a role in helping me emerge as an artist. There was always a deep pained sensitivity and passionate hopeful sorrow driving me to create, but I was also influenced by my environment, friends, and teachers. The natural environment I grew up in aided me in the process as well. I am not separate from any of this. I do feel like the forced capitalist ownership can sever the force of what we offer one another. Very well put! I think that music and art still have the ability to overpower those false barriers and that’s why music and art can never be truly contained or controlled. Music is collective. Music is meant to be created and given; absorbed and received. Yes, I agree about an ancestral line of women’s lost voices. The women’s culture Starhawk speaks about in her book Dreaming the Dark highlights a collectivity, a power with, a power amongst all creation and all living things, “heaven” and “hell” are here on earth not transcendent. To compartmentalize and sell creative work as a product has never come easily to me because of all these spiritual, emotional, and intimate cultural factors. However, pragmatically speaking, it is incredibly important to support artists monetarily. JD: In thinking of the concept of intergenerational haunting, the idea that the traumas of our ancestors live on in our bodies and psyches, a telescoping of generations that continue as hauntings until they can be acknowledged and repaired, I'm wondering if, for women, these hauntings are perhaps more pronounced and grievous, given the immense suffering and alienation imposed on women for so long by our exploitative and disembodied, dis-souling economic system? It is said that one must transform one's ghosts into ancestors, meaning one must work through what has been done to our ghosts in order to arrive at an ancestral now that lives healthily and honorably with one's past, and the people of our past. Does this at all resonate with your vision and hope in Immanent Fire? Do you think part of Immanent Fire is about turning ghosts into ancestors through the act of acknowledgment, untanglement and voicing, not just the value of intergenerational women, but the existential, spiritual necessity of women and our need to make room for generations of grievable, lost voices? EJW: I really love this question. I feel like my work might be a healing of this intergenerational trauma and haunting you speak of. I have at times been weighed down by feelings and sensations that are mine, embodied in my being, and at the same time dissociated, fractured - coming from a different time and place. I’ve always been sensitive to the brutal violence inflicted on women for centuries, and this sensation and concern feels like it runs historically far beyond my birth on this earth. I am a product of many generations of trauma and addiction and I grieve the women who struggled immensely before me. I feel like my work has faced untanglement and given voice to this undercurrent, and collective undercurrent. In this record I am very much calling for the existential and spiritual necessity of women and our need to make room to grieve and to rebirth. In order to honor the immense potency within all of us, perhaps we have to grieve all that’s been lost and connect to those disavowed voices, lives, energy, love, and vivacious women’s culture that once thrived more harmoniously in order to create this in the here and now. I don’t believe it’s dead, I believe the potential to reconnect, to heal, to grow through the trauma, the damage done to this earth and all the many people and living entities living on it is possible by reconnecting to this concept and felt sense of Immanence that Starhawk speaks about. JD: Music enters into our bodies, sound awash and through us, reverberates down into our bones. It is what opens us to presence (sound cannot be denied) it comes to us unbidden, each time a surprise, while also opening us to dreaming and infinity, it becomes a liminal space, a crossing from present presence to unknown and creative river beds of potential, of change and transformation. How do we learn to expand on those moments? How do we take them with us? How do we keep feeding the flame in a world that prioritizes smothering the flame, killing the dream and destroying the liminal crossing that music and art open up in us? EJW: You're speaking directly to this idea of “Immanent Fire,” this flame, this potential, this dreaming, this liminal space, this creativity, this desire for things to be different, an honoring of the self and all beings here on earth, connecting to the vastness and healing potency of life. It is within us and it will always be within us. What taps into this space the most? There are certainly many things that can suffocate the flame, or cause it to dimly burn. Continuing to connect again and again to one’s own potency through art, music, nature, engaging, creativity, somatic modalities, meditation, dance, each other, revolutionary politics, or whatever speaks to you, seeks to change current conditioning. But - we must continue to stand up to systems and institutions that thrive on the exploitation of our vital selves, communities, and resources. There’s a struggle, and there’s a deep fight involved. You have to be willing to stand up and empathetically fight for people you don’t know and will probably never meet. It is my hope that music can be an agent and travel to people and places who need it most. Immanent Fire is available now from Talitres and Bandcamp. Visit http://emilyjanewhite.net/ for more. 2/17/2020 The Parody by Daniel R. Adler Nathan King CC

The Parody The drugs have changed him. The word might be fried, he’s heard that before, though that is a metaphor and he eschews figures of speech. He eschews speech in general. Words are human and in this haze, this muddled confusion of his day to day reality, he prefers to think of himself as a wolf, an ape, a hyper-evolved human returning to more primitive animal-vegetable roots. It’s not altogether unpleasant, the uncertainty of whether he’s living in a dream or reality; the oneiric nature of his waking hours and the realism of his reveries bleed almost indistinguishably into each other. It is dusk, and a veneer of pollution hangs over the sky. He sits in a white plastic chair at a white plastic table. A wasp floats over an ashtray. He lights a cigarette and wordlessly begins to think, to remember—past and future—in images that come to him in a blur of temporalities that stretch across millennia. A carnival tent, red and yellow striped—the first circus he witnessed—a ringleader snapping his whip near a lion’s snarl, his red shirt with brass buttons and matching cap, white pants, black boots. The hot pinks and bright oranges of carnival games, children’s squeals, the watergun squirting into a plastic clown’s mouth. The man who handed him the small teddy bear, his thin biceps under a pack of cigarettes rolled into the left t-shirt sleeve, the long greasy mullet—such underworld beauty, that was not the phrase he thought, none of these are the words he thinks, he avoids thinking in words, but that was how it registered on him, admiration-inducing, a blatant disregard for social norms, the gypsy life, so that when he left home to escape his father’s brown belt, to avoid any more keloids on his back, his thighs, at sixteen he went to the state fair to inquire about work, and he sat with Cynthia, whose black-gray hair, compressed by her violet head wrap, surrounded her cheeks like cotton candy, it was instinctively clear, which Cynthia confirmed for him when she looked into his gray, wolflike eyes—he was a gypsy once, and was again, a butterfly in a past life, a caravan in an empty field, aunts, uncles, stringy children squatting with sticks, nomads sitting in tallgrass, a fire crackling—the same posture struck by these carnies, his male ancestors leaning against a wooden exterior, trees, huts, caravans, hands in pockets—unconsciously he floats between the conscious reality of Joseph leaning against his double-wide and the subconscious reality of his male ancestors on the steppe, somewhere between dreams and death, he follows these threads of reality, oneiric, chthonic, sensuous, instinctive, to understand that’s he’s been living this life for centuries, one bleeds indistinguishably into another, eight centuries ago in the foothills of the Caucasus impossible to distinguish from an afternoon setting up tents near an abandoned farm in Florence, South Carolina. He and Cynthia knew each other then, when their band paused near the Caspian—but now the scent of corn dogs and cotton candy brings him fully into the present and he drags again on his cigarette to fight off the gentle movement of his stomach that indicates hunger. The cigarette has burned down and he crushes it out. The ashtray wasp hovers, floats, lands on his hand, crawls, time suspends as the wasp’s legs flicker across his knuckle—the wasp departs. His existence will go on for centuries more, thousands of lunar months, decades, his essence will float nomadically, oneirically, chthonically, across space and time, with hardly any will of its own. It’s not unpleasant, this vegetable existence, animal when his instincts kick in, though it’s been a while since even those have moved him to action—Joseph supplies him with enough drugs to mute those in exchange for three quarters of his paltry salary. Distinguishing between quality is irrelevant and unimportant, he simply takes what is given, takes and uses and sleeps and wakes and drifts through the monotony of existence, not unpleasant. A crow caws, perched on Joseph’s trailer for what might as well be a thousand years—his mind, muddled and confused, is better able to endure the banality of these comedowns, the false desire for more through the power of his subconscious, which manifests so strongly while awake that he no longer dreams at night, or if he does, he cannot remember how or what. His body, mind, is wasting away, although that means little, he’s been wasting away for years, he won’t living into his fifties, his type is such that he’s rarely hungry and when he eats an ear of corn it’s enough to get him through an entire day. As far as actual responsibilities, he’s long contented himself with being assistant to Joseph, who runs the Water Gun Game. He collects cash from the peds, as they’re called, and watches as they race each other to fill up the colorful balloons that rarely burst, now and then he hands over a stuffed pink elephant upon exhortation from Joseph, mostly he smokes and stares into the sky. The movement of their nomadic troupe, the drugs, the syndicates Joseph and the others know around the country, their network and knowledge allow him to live this way, squirreling away cash in a bag, a few hundred leftover after buying the heroin or meth, enough savings for any disaster he’d have to weather before finding himself another carnival. But that would never happen, they are a family, Cynthia the fortune-teller, Joseph, the others whose names he’s forgotten—they’ve been working here under Shep, the man who runs the show from above, they’d never let anything happen to him, not after twelve years. A murder of crows croak across the sky, the same way it was twenty thousand years ago, when he lived in South Asia, when his traveling band lived like animals, searching for roots and berries, sleeping under the cover of broad leaves in tropical warmth—over eons like this, crows squawked across the sky, searching for carrion, and he entertained the others with a ball and stick game. The machinery today is different but his efforts are the same, the intensity of his existence oscillates more greatly, is more dependent on the drugs, whereas it used to be dependent on the seasons. It will continue like this, even after the natural disasters and plagues that Cynthia prophesies toward the end of their lifetimes, they will be reborn into another version of this, to roam the taiga or the mountain plateaus of Mexico. Right now, all he is certain of is the crows cawing across the sky, the passing of lunar months, of decades and quarter centuries, of his position as he leans against a wooden exterior, that ancient stance of hands in his pockets or—before and after pockets—akimbo. Daniel R. Adler was born in Brooklyn, NY, and has lived in Portland, Oregon. He studied literature and philosophy at NYU and creative writing at Edinburgh University. He is finishing an MFA in Fiction at University of South Carolina. His work is forthcoming from Eastern Iowa Review, The Broadkill Review, and has appeared in Entropy, Queen Mob’s Tea House, Five2One, The Opiate and elsewhere. 2/17/2020 Poetry by Joseph GooseyIn Which Pleasure Elf Reads An Article Stating One Need Not Panic About Passing Mental Illness Onto Children then makes a cheese sandwich, chugs a road wine, and imagines some gods in order to pray. I stand at the intersection during your favorite hurricane waving a handmade sign saying I Will Be Devout In Exchange For Proper Blood Flow as if to sell mattresses. Ever read, not see, but ever read The Shining? Things do have the potential to be okay. Joseph Goosey lives in North Carolina. His poems have appeared in The Fanzine, Wussy Mag, Cordite Poetry Review, 8 Poems, and elsewhere. Author of the chapbook STUPID ACHE (Greybook Press), his first full length collection is forthcoming from EMP Books. 2/17/2020 Poetry by Kiki Dy Richard P J Lambert CC The Last All You Can Eat We were on the cusp of chaos Loitering in QwikMart and we asked them To turn the music up and they acquiesced Because I wasn’t wearing a bra And you had a gun But maybe I’ve rewritten that in the retrospect And there was no gun And maybe I’ve rewritten it all Because when someone dies The ability to reminisce dies with them And all of a sudden there are guns in QwikMarts And quiet conversations about desire on rooftops There are secret glances at In-n-Out burger Where you get close enough that the inch between our noses holds everything that I wish I distilled Because sometimes when it gets late enough And quiet enough I drive in the dark toward what I hope is some version of truth But it is not because you are not here to tell me whether or not there was a gun or if the waitress at Gyu Kaku had a mole on her left eye Or if I really was a bitch that night with the plumber Or if I was a gracious, giving friend Or whether we loved each other ferociously or Just capably at best And I will never know any of this Because when someone dies The ability to reminisce dies with them And you black out in your car Never knowing what is true And what is a wish made up in your head Abbey Hated My Boyfriends I am trying to let my illusions last and with this comes with the consequence of blindly crying love and forcing Half-Puerto-Rican men into my heart when really all I crave is a delectable loneliness But I tell myself I can’t have this because there is great comedy to be spurred from mistakes So I make the mistakes and thrust myself hard into them banging opposing egos together like flecks of flint trying to make sparks that spell out This was me, I was young But at what cost 3. I am starting to forget your touch The smooth of your massive tits The exact damning decibel your laugh could reach I am starting to summon you in cheap sunglasses Casting an earth spell by Commissioning a kiddie pool full of Xanax and glitter I see your happiness in a bowl of rice Then I eat it Maybe that’s what I always did I try to rewrite it without my selfishness and sadness Without our addictions But I continue to summon you in baby benders A bottle of wine, a gram of coke, then three valium to offset it And I am prone on the Moroccan rug staring into the ceiling Convinced I have conjured you back “Let’s go” I say and my lids surrender onto themselves I dance with your dingo and laugh with your lungs You put on my grief and I put on your bra How fun it is to have nothing to do But laugh until five, hula hooping with you  Kiki Dy is a recent MLitt graduate from The University of Aberdeen which she decided to attend in an emotional fugue. She is allowing herself a victory lap in the Scottish bar scene and inboxes of literary magazines before she likely decides to attend law school or perfect her quiche as a welcome lark. 2/17/2020 Eftsoons in poetspeak by T.A. YoungEftsoons in poetspeak Eftsoons in poetspeak The last draught We ambled to our cars Mumbled and waved Without raising our eyes To beer companions And hit the gas. We know the faces Weariness belying cheer Screen doors not worth locking Grassless lawns Like the ten o’clock shadows of Inmates cinder blocks for flora. Burnt and drained And nothing new on cable. Too tired to not think Of days when he was another Changing dead bulbs soon as they Sparked out. And a voice would come from another room. Are you home? Now, you say to no one, I don’t know. Going straight for the fridge Reaching for a bottle of loneliness In poetspeak To assuage the loneliness In poetspeak He falls asleep in a chair, One foot on the ottoman The glare of the sun through The screen door will awaken him He’ll see that he never even took a tug From the now-dead bottle And he hasn’t changed his socks in days And will another day One more day Make any difference, Even in poetspeak? T.A. Young is an author and poet who lives in NYC. 2/17/2020 Poetry by Shannon Austin Richard P J Lambert CC Never Where You Left It Poltergeists are usually associated with an individual. Hauntings seem to be connected with an area. A house usually. –Dr. Lesh, Poltergeist Say she is the house. This hallway, leading to a heart. That staircase, spiraling to a hive. Chairs & memories never where you left them, sliding over linoleum tiles forming heads of sunflowers. Say house when you mean home. Say she is the marble stoop where you ate shaved ice & watched the sun sink below denim skies. Stained glass above a doorway naming its numbers. A deck, torn down. Built from its bones. Say there’s no poltergeist in Poltergeist. No, that can’t be right. Werewolf During a Lunar Eclipse I am religious under an empty sky. Mountains liquefy into vertical plains & nothing asks for belief. Sometimes faith depends on spite. I must remember who I am in the dark. The urgency of myself, before other bodies hunger. The Lake You step in & the thing is you drown or step out, feet webbed under the clear clouding of your pedicure; eyes blossoming into thousands; worlds wakened in your marrow. Blink & feathers free-fall down your back, swooping into frowns & sighs. Words float beyond your limbic shores, slipping syllables & guttural urgencies escaping your neighbor’s terrier. The ability to lift yourself out of bed. Transport matter across distances. Change the density of an apple. Composition of a nail. Comprise a saltwater pond. Gather the strength to step in again.  Shannon is a writer from Baltimore, MD, with an MFA in poetry at UNLV. Her work has appeared in Colorado Review, Rust + Moth, After the Pause, American Chordata, and elsewhere. 2/17/2020 For Redacted by Daire ShawFor Redacted I have never needed an abortion I have been lucky, very lucky I was pregnant at the wrong time By the wrong man but I was lucky Though there was no morning saviour Then, I knew that I could choose to Keep or stop the sprouting thing that Let alone would change my life forever I was lucky to have a choice to make Or at least I was close enough to a Place whose choice and open-to-me Borders I could borrow, and I did Later I sat in a small white room With a nervous spotty boy who Asked me questions and I lied Through my clenched teeth I signed my lies to swear the truth And that I knew the consequences To spare a young girl his questions And weeks later, I did that again In a different room with a different Strange man with a nametag I signed My lies and took the two small pills I made them illegal giving them over To her and holding her hand while she Shook and turned green on my couch Because she was not lucky And I’ll be damned If she doesn’t get a choice  Dáire Shaw is a queer Irish multimedia woman artist from Wicklow, Ireland. She works primarily across art, photography and poetry, and is currently pursuing an honours degree as a mature student in art photography at the Institute of Art, Design & Technology, (IADT) Dunlaoghaire, Ireland. Dáire is deeply interested in exploration of the human condition at its intersection with meaning through art and symbolism. On a personal level Dáire uses her art in an attempt to understand herself and the interstices she shares with the world she finds around her. Dáire lives in Wicklow with her daughter, Ruby Rose, two small dogs, Sadie and Penelope Tuppence, and a calico cat named Clementine Clover Murderpaws. |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

April 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed