|

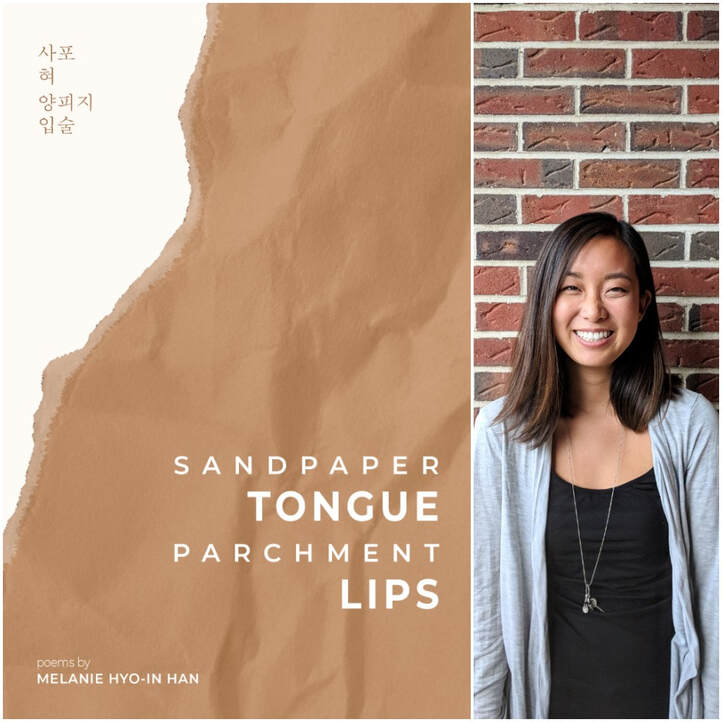

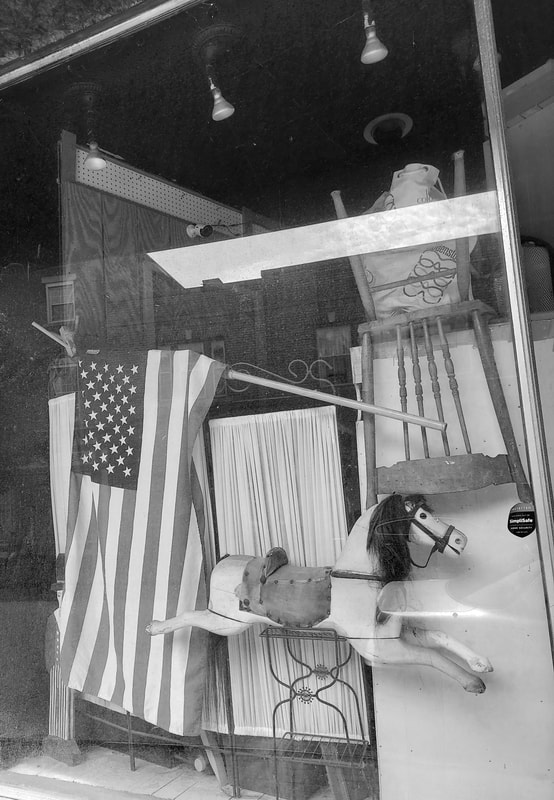

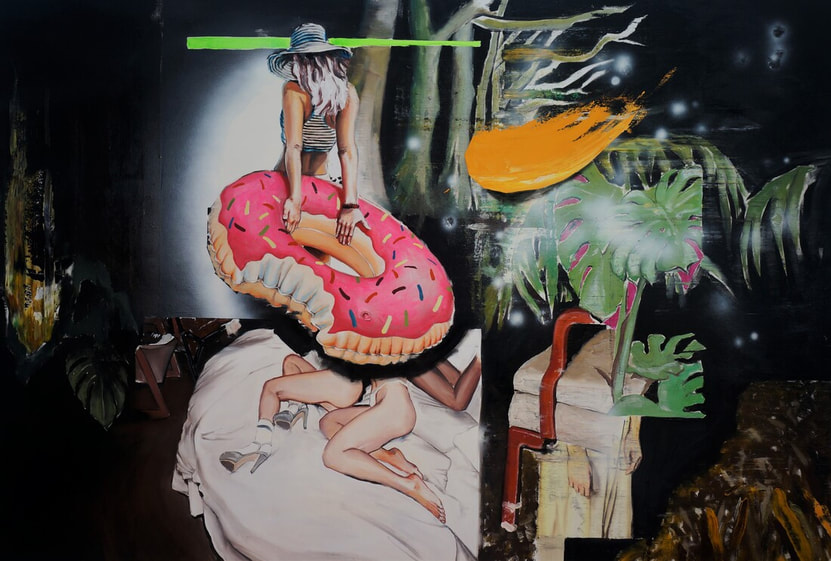

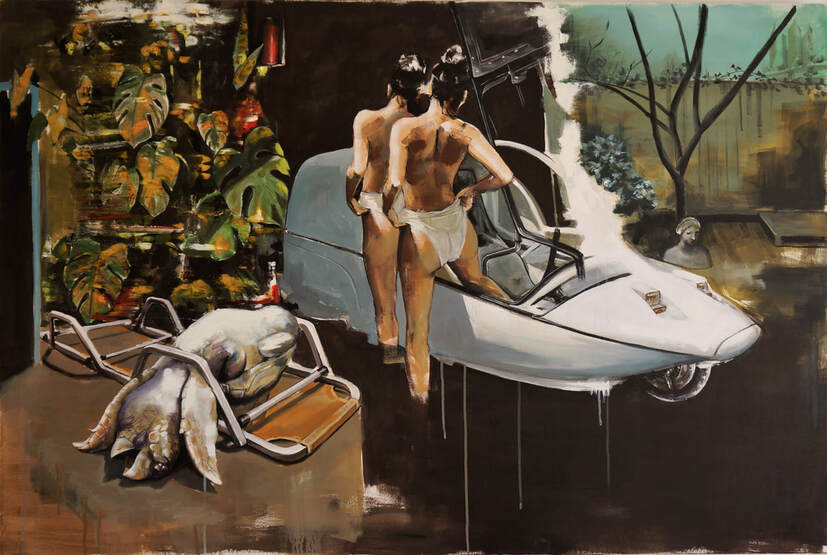

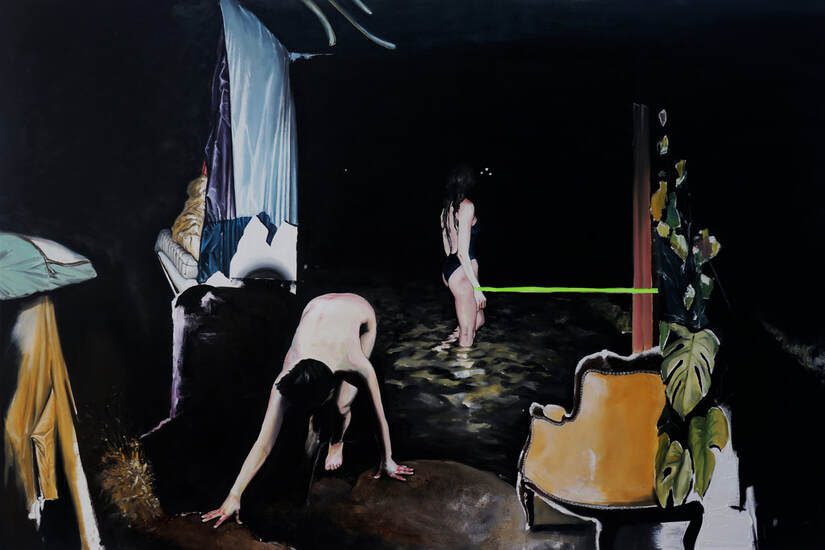

Arizona natives, Austin Davis and Joe Allie's haunting poetic/musical collaboration, Street Sorrows, is an intimate and empathic howl of an album of, and for, the voiceless of America. Austin recounts here the daily sorrows and struggles of those living on the streets of Phoenix, accompanied by Joe's powerful and intuitive musical score. We talked with Austin and Joe recently about the album, their collaboration, and how "the most valuable thing we can do for another person is show them we care." AHC: Can you tell us about the origins of this project? How did it first germinate for you? Did you write these pieces especially for a musical project or were they selected after the idea for this collaboration came about? Austin: I’ve had a lot of difficult, scary and painful experiences with people on the streets. I’ve seen dead bodies. I’ve seen overdoses and heat strokes. I’ve seen people stabbed and beaten and bloody. People have wept in my arms and told me they want to kill themselves. I’ve known friends who’ve died. I needed to process all this heartache, so I started to write about it. Early on, I would cry and cry for hours in my car and scream at the top of my lungs for it to all stop. When I started writing these poems, it felt like I was draining my brain of some of that pain and putting it down on something tangible that I could feel in my hands and share with the world. I was set to read some poems on Desert Spotlight, a really cool AZ arts show, and I asked if we could collaborate with a jazz musician for the show. That’s how I was introduced to Joe. I felt like our artistic chemistry was born instantly, and that show with him was the best performance I’ve ever done. On this show, two of the poems I read to Joe’s guitar playing were about homelessness, and I felt like those were the most powerful moments of the episode. After the show, I asked Joe if he’d be down to create an album together about homelessness and he was all in. The poems on this album took a long time to write, but we recorded the record all in one night at Joe’s house. The amazing Brent James produced this project and really brought my words and Joe’s sound to life. Brent was such a huge part of this project, and I feel eternally grateful. AHC: I was struck by the deep level of direct, unadulterated empathy and listening to the pain of those around us that these pieces represent and speak to. Can you tell us some about the people that we meet in these tracks, and your work within this community? Have they had an opportunity to read these pieces or hear these tracks yet? Austin: All the people on this record are based on real people and real moments I’ve shared with these people. I wanted the songs on this album to shape a world, to allow the listener to step into these lives that may feel so separate from theirs, but are also so connected to them by our shared humanity and vulnerability. Phoenix is made up of lots of little scenes. I vividly remember seeing people splash around in a lake to cool off from the heat. On one winter evening I found a couple holding each other on the sidewalk for warmth and comfort, and I was stopped dead in my tracks from the supreme sadness I felt. Last summer, a woman I knew had to pee in the bushes because there were no public restrooms that would allow her in. This poem is a message to our city and elected officials. Leo & Hazel is about a specific evening I spent in “The Zone,” which is the central tent city in PHX, and the area that I go to almost every day. This is one of the areas where I know almost everyone living there. In some poems, we use memory as a stepping stone to create a story, but with this piece, I really just wrote down what happened and how I felt in the moment. We were sitting on their cooler talking about the past and the good times they had had before they were sent to the streets. The sun was setting in brilliant colors and I felt it juxtaposed with all the suffering around me. In Pennies, we meet Roy. The silent killer of people on the streets is loneliness, and I don’t feel like that’s talked about enough. It can get really lonely experiencing homelessness, especially when you’re doing it alone. I knew I wanted to write about this loneliness, but I didn’t have a vision for what I wanted to say until I met Roy. I met Roy outside the mall I went to hundreds of times as a kid and teen. We talked about mental health and loneliness and he told me how much it means to him to feel he has a friend, to feel cared for and valued, at least for a moment. We talked about what he misses from the past, what he’s afraid of, and all the scary thoughts we try to hide from the world. To answer the second part of your question - yes! I’ve shared these tracks and my poems with some friends on the streets and I’m even planning on picking up some folks around town on the night of our album release show because they want to come watch us perform live. AHC: The location is very much its own character in this project. Phoenix, a thing in your blood and soul, I imagine. It sounds like the pain and desperation in that area is palpable. Not everybody takes it upon themselves to stop, lend a hand, listen to a story of where one has been, and try to make a small difference. What would you like people to know who are disinclined to do so, what small thing might they do that matters to those who need it most? What first called you to do so? Austin: The city of Phoenix is as much a part of me now as my skin or hair or eyes. I feel connected to these people, like we do with family members or old friends. We’ve experienced a lot of pain and loss together, and in a way, that brings us even more together. I often tell people “It’s all love,” when they thank us or hug me or ask why we do what we do. One of the most valuable things you can do for another person is show them you care. If you see someone experiencing homelessness on the side of the street or outside a grocery store, it’s so valuable to just stop for a few minutes and talk and ask how they’re doing. You might just save a life. That’s how I started this work. I began by meeting people and hearing their stories and developing friendships with them. Eventually, I couldn’t stop thinking about the streets and I felt I needed to do something more. AHC: Where can people get a copy of this excellent album, and are there any organizations you'd like to tell people about that help these communities and that people can donate to or help spread the word about? Austin: “Street Sorrows” will be out on Apple Music, Spotify, iTunes, and all major streaming services on July 30th. I hope that this record will make people look at the homeless with a little more empathy. These people deserve love, respect and dignity, just as much as you or me. The program I run in Arizona is called AZ Hugs For the Houseless, which all the proceeds from this album will be going towards. Here in AZ there are lots of great groups to donate to and get involved with like Feed PHX, The HOPE Project, the ARA Water Foundation, and more. If you want to get involved in your area, you could start by simply grabbing some friends and freezing some water bottles and hitting the streets to talk with folks! *** AHC: What was your musical process like collaborating with Austin on this really profound and powerful record? Joe: The musical process working with Austin was very open ended. There were no hard rules or requirements I needed to fulfill which made the whole thing very creatively freeing. We did go back and forth on a couple of poems that I would read over, and then we narrowed down our first performance off the poems we all agreed upon. On my own, I would read the poems and focus on dissecting the feeling and emotion in each poem. This all helped me make my musical decisions. AHC: Your music on each of these tracks feels very intuitive and I can feel and hear the very soul of Phoenix, and of the people in these pieces, coming through in your compositions. There is a sorrow that the notes draw up, but not a sorrow of resignation or defeat, and I noticed something else, also, as I was listening, a kind of gentle tap on the shoulder. I was struck by the power of your musical accompaniment: as Austin's pieces are all about accompanying those around him, in pain and in need, your score accompanies Austin and the people in his pieces in a very similar (empathic) and direct way. What are your thoughts on that? How did Austin's pieces, and the stories embedded in them, move you as you wrote the score for each of these? Joe: I am an Arizona native of 26 years. I was born and raised in various parts of this state. It was pretty easy honing in on the feeling of each poem because these are all things I have witnessed in our home. These are all things I have felt to some extent; Austin just does a really good job putting it into words. I tried my best to stir up those emotions and support the message of each of these poems through the music, but Austin and I found our common ground through Arizona and from our shared experiences of this place. AHC: What has been your musical philosophy, your guiding principles of sound that you've carried with you in your toolbox over the years? What have your teachers or inspirations taught you that you try and hope to teach others about the power of sound? Joe: One of the biggest lessons that I have carried with me throughout my musical journey is to learn as much as you can from others. Whether it's taking lessons or learning your favorite songs, there is a lot that you can get out of learning other perspectives. It provides you with other tools that you can combine with your own to create something better. As far as what I have learned from my teachers, the main takeaway is the power of listening. When you are first learning an instrument it is easy to get carried away and only focus on what you are playing; not what you are contributing. It's tough though because you really just need to be able to play the instrument before this task can be achieved with ease. Learn to listen first before you speak. I believe this lesson can be applied to much more than just playing music. Of Melanie's forthcoming collection, Sandpaper Tongue, Parchment Lips, Rajiv Mohabir writes: "Melanie Hyo-In Han asks what it means to be an outsider to both language and place while returning the reader-cum-witness to the house of poetry... The migrating body thrives in rainy seasons, in heartbreak, in alienation, all while baring the intimacy of presence and poetic line. And Livia Meneghin adds that: "each poem offers an invitation to explore family and place with an elegant assuredness, a tender guide. Sandpaper Tongue, Parchment Lips not only asks, “Can I Roll, Slice, Stack Memories?” but also, “at what cost?” We spoke with Melanie recently about her forthcoming collection of poems, which can be preordered from Finishing Line Press. AHC: Can you tell us a little bit about your upcoming book, Sandpaper Tongue, Parchment Lips? Melanie: Sandpaper Tongue, Parchment Lips, is a collection of poetry based on my experiences as a TCK (Third Culture Kid) growing up in East Africa and facing struggles around identity and racism, as well as cultural and linguistic barriers between me and my Korean family. Throughout my childhood, I had to come to terms with who I was as I dealt with deaths, drought, bullying. The chapbook focuses on heartbreaking events and sad memories, but also joyful moments that have shaped me into who I am today. AHC: Your book, in part, is a tying together of experiences in different cultures, languages, homes. In migration: a kind of heartbreak. Are there any poets in particular who've been an inspiration to you in writing through similar terrain and experiences? Or poets who, when coupled together, seem to speak through their differences into a kind of universal flow? Which poets do you find and return to in your toolbox? Melanie: There are three poets that come to mind, each who address topics that I deal with in my chapbook in their own, very different ways: Sara Borjas, author of Heart Like a Window, Mouth Like a Cliff, is a Chicana poet who struggles with cultural assimilation and what it means to think about her Mexicanness in the context of living in the U.S. In Thrown in the Throat by Benjamin Garcia, the author talks about the complexities of language, identity, and culture. Last but not least, Philip Metres writes a lot about the concept of "home" and how that plays out in the midst of war and tragedy. I find myself reading through the works of these three poets often, especially because they give me inspiration to continue thinking through my own identity, culture, and what "home" means. AHC: What comes to mind when you think of home? What's the ineffable you aim for in a poem, but that perhaps, inevitably, some part of the poem must miss? Melanie: "Home" to me has never been a location, though, in some ways, I really want it to be a single place that I can pinpoint on a map. I think "home" has become an idea that is abstract, rooted in people and memories rather than a specific location. In my poetry, I hope to give readers the sense of belonging and a feeling of hope, similar to an emotion one might feel at "home," but through words and experiences rather than a concrete place. AHC: How did you first come to poetry, or, perhaps more aptly: how did poetry first find you? Melanie: Poetry first found me when I was lonely and I didn't have ways to really express how I was feeling to others. Through fragments of words and images, writing became one way I could reflect on my emotions, which eventually turned into more developed pieces that I could turn into poems. AHC: What are a few of your favorite poems? Perhaps poems many don't know of, but should? Melanie: Honestly, I love every poem written by Emily Jungmin Yoon, a poet whose main area of focus is inherited trauma in Korean women, as well as gender, race, and history. I'd highly recommend Ordinary Misfortunes and News for anyone who wants a taste of her poetry. AHC: How do you know when a poem is done? What makes it click? Melanie: I don't think a poem is ever really done! There are poems I wrote 5 years ago that I still return to and make small edits, perhaps add in a line break here and there or put in an additional punctuation mark. However, I do feel like it's ready-ish to share with the world once I've written it, revised it (lots and lots of times), left it alone for a bit, and then made a few more edits. AHC: Do you have any words of advice for other poets, perhaps most especially those starting out, still searching for their voice and that sweet spot in a poem? What words of advice from others have helped you along your journey? Melanie: My one piece of advice would be to "never be afraid of experimenting." Whether it's experimentation through form, images, concepts, etc. I think there's so much creativity within each person that is just waiting to come alive but might be held back by what we are taught as "traditional poetry." Writing is a form of expression, so I think I would encourage people to just write and see where it goes! Sandpaper Tongue, Parchment Lips is available from Finishing Line Press. 7/31/2021 Photography by Jason BaldingerJason Baldinger is bored with bios. He’s from Pittsburgh and misses roaming around the country writing poems. His latest books are A Threadbare Universe (Kung Fu Treachery Press) with The Afterlife is A Hangover (Stubborn Mule Press). His work has been published widely across print journals and online. You can hear him read his work on Bandcamp and on lp’s by the bands The Gotobeds and Theremonster. 7/31/2021 Artwork by Stefan Doru Moscu I have been here many times before, Acrylic and oil on canvas, 2019 Try to name what you feel and the feeling is gone, Acrylic and oil on canvas, 2018 I'll use you as a focal point, Acrylic on canvas, 2016 There's just nothing I'm running from, Acrylic and oil on canvas, 2019  Stefan Doru Moscu is a visual artist, born in 1982, living and working in Brasov, Romania. He received a B.A. in Art and Restoration from the State University of Sibiu, Romania, and works with both painting and sculpture. Stefan’s surreal paintings explore society’s transformation from the past to the present. He culls inspiration from decaying objects, old photographs, pop culture and art history to present a critical view of various social, political, and cultural issues. His works are characterized by a darker color palette and obscured figures, giving his compositions a somber mood. Stefan had an artist’s residency at Glo’Art in Belgium in spring 2015 and 2017 and has exhibited his works in the US and across Europe in countries including the United Kingdom, Germany, Belgium and Poland. Most recently, his works were part of “The Other Art Fair” in London and “The Sea/Das Meer” international group exhibition at Group Global 3000’s Projectspace in Berlin. Insta: @stefandorumoscu Twitter: @MoscuStefan 7/31/2021 Artwork by Zainab Iliyasu Bobi Blue flame  Zainab Iliyasu Bobi, from Bobi village in Niger State, is a Nigerian photographer and writer. She was a finalist of the Voice of Peace anthology. She is the treasurer of Hilltop Creative Arts Foundation, Abuja branch. Her works are published and forthcoming in The Kalahari Review, Blue Marble Review, Sledgehammer Lit, Praxis, Words Rhymes & Rhythm, and The Shallow Tales Review, among others. Twitter: @ZainabBobi 7/31/2021 Photography by Melody Wang7/31/2021 Artwork by Neall Calvert Hospital during rainstorm Small Town, 5 a.m. The gang's all here  Neall Calvert has 25 years' experience as a journalist, book editor, writer and photo artist. His images hang in homes and offices in Vancouver, Canada, and appear in books. He now lives in Campbell River, British Columbia, near the quiet and wildness of northern Vancouver Island, where he's building an image collection called "Raining Glory: Campbell River by Night" and writing a prose/poetry memoir of his long healing journey out of the calamity that is childhood religious violence. |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

April 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed