|

7/29/2023 Photography by Christina A. KempChristina A. Kemp lives in the Pacific Northwest and is the author of the memoir Across the Distance: Reflections of Loving and Where We Did & Did Not Find Each Other. She has an M.A. in Counseling Psychology and is an artist, healer and teacher. Her work has been featured in the anthology True Stories: The Narrative Project, Vol. III and Last Leaves Magazine. 7/29/2023 Photography by Kirsten SmithFoggy Pines Path Through the Sequoias Secret Stairs

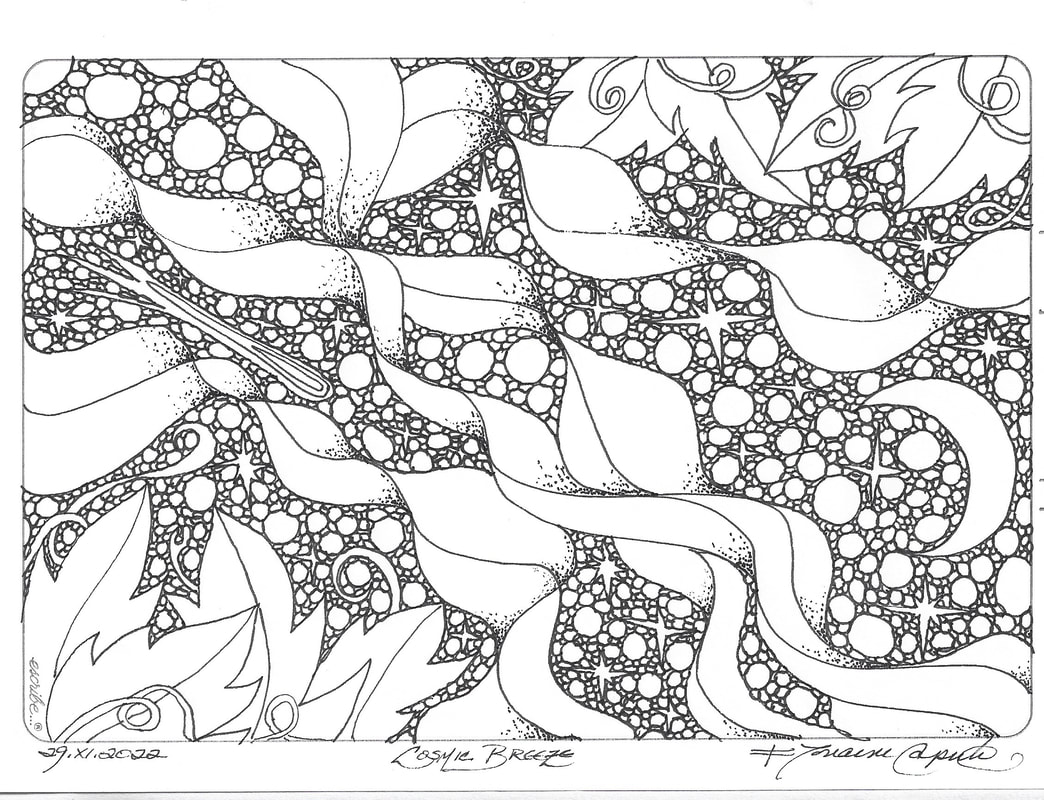

Kirsten Smith is a photographer, writer, and travel-addict who lives and works in San Francisco. Her work has appeared in (or will soon appear in) SPANK the CARP, Esoterica Magazine, JAKE the Magazine, and elsewhere. Check her out on Instagram: @the_wallflower_wanderer, and Twitter: @Kirsten_Wanders. 7/29/2023 Artwork by Lorraine CaputoCosmic Breeze

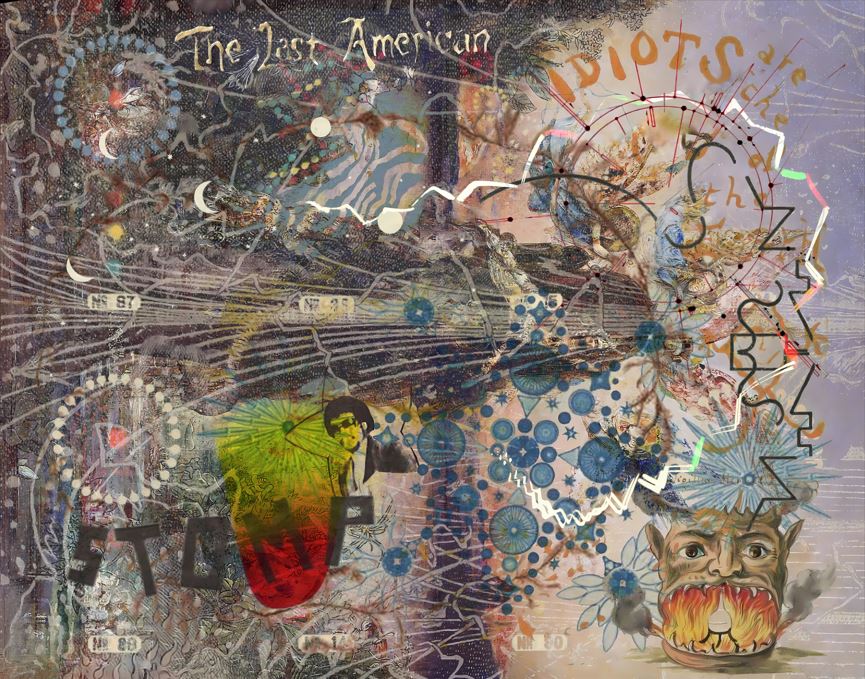

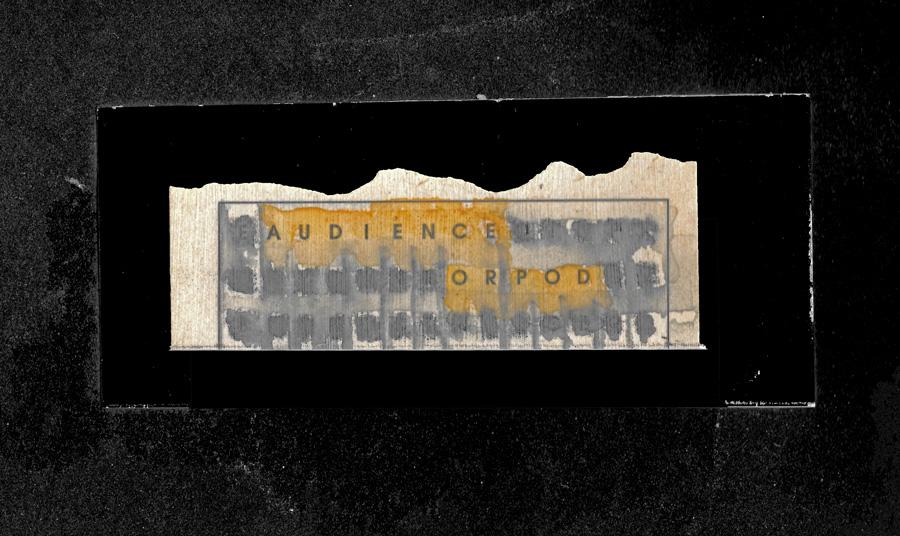

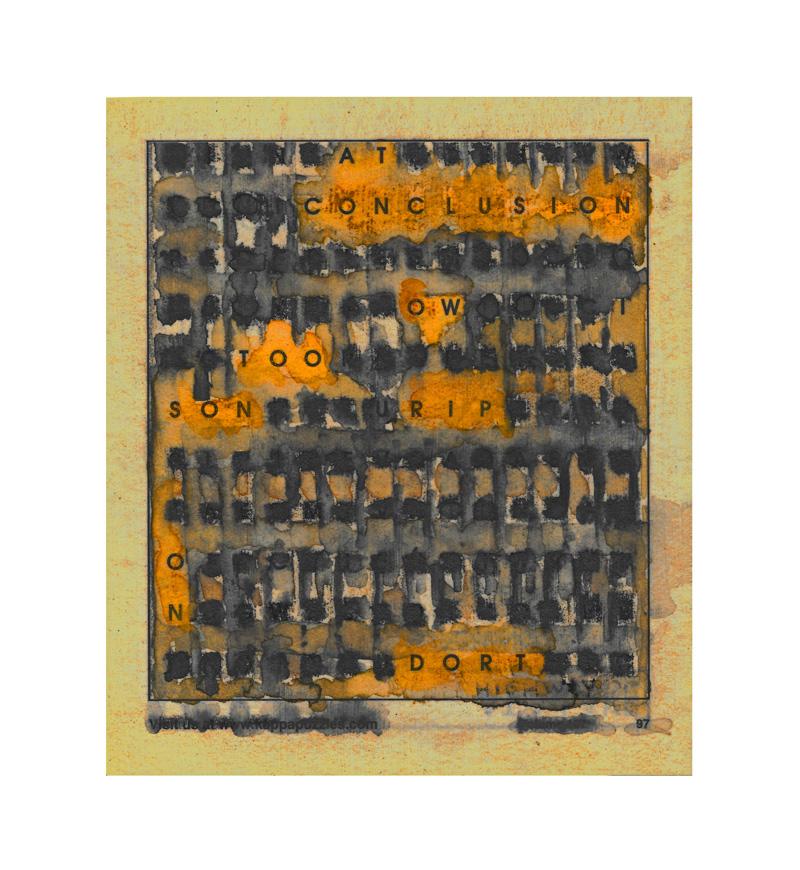

Lorraine Caputo’s artwork and photography are in private collections on five continents, in the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo (Chachapoyas, Peru), and has been exhibited in the US and Ecuador and several publications, including Thimble Literary Magazine and Ofi Press (Mexico). Her poems and travel narratives appear in over 400 journals on six continents and 23 chapbooks – including In the Jaguar Valley (dancing girl press, 2023) and Caribbean Interludes (Origami Poems Project, 2022). She has done over 200 literary readings, from Alaska to Patagonia. Ms. Caputo continues journeying south of the Equator. You may view more of her work at Latin America Wanderer https://www.facebook.com/lorrainecaputo.wanderer and https://latinamericawanderer.wordpress.com. 7/29/2023 Artwork by Anthony SantulliLeaves turn Still life for Rachel Ruysch Balenciaga collage Moon spore, Sun's poor

Anthony Santulli (he/they) is a New Jersey born writer with a B.A. in Creative Writing and Italian from Susquehanna University. Their recent work has appeared in Heavy Feather Review, minor literature[s], petrichor, COUNTERCLOCK, Beaver Magazine, and BRUISER. 7/29/2023 Photography by Jacelyn YapIn Between #03 In Between #13 In Between #04

Jacelyn Yap (she/her) recently started focusing on her art proper, having persevered through an engineering major and a short stint as a civil servant. Her artworks have appeared in adda, Sine Theta Magazine, and Olney Magazine. She can be found at https://jacelyn.myportfolio.com/ and on Instagram at @jacelyn.makes.stuff 7/29/2023 Artwork by Koss Koss is an artist, writer and web designer with over 200 visual and written publications in journals and anthologies. Recent and forthcoming publications include MoonPark Review, Sage Cigarettes, Beaver Magazine, Anti-Heroin Chic, (Re) An Ideas Journal, Permafrost Magazine, Cutbow Quarterly, Petrichor, and SoFloPoJo. Find links to Koss's work at https://koss-works.com and connect on Twitter @Koss51209969 and Instagram @koss_singular. 7/29/2023 Whisper It All by Antigone Gambleminka6 CC

Whisper It All We are sitting at stools around the tiny kitchen counter, all of us small atop even smaller bar stools. Red digits on the alarm clock radio blink, 6:55pm. We are eating ice cream, me and my little brothers. Laughing, the humming and beeping sounds of the microwave, the white noise of the evening news, dishes being scrubbed and stacked, a cold spoon clinking in the foreground. I am doodling on a yellow note pad with bright red ballpoint pen; the smooth silky strokes it produces, the faint yet comforting smell of the ink. The room is warm and electric. When you flip the page there are thin raised lines, like cat scratches on an arm. I run my fingers over them. And then there are waves... crashing. My dad yells down the stairs. "Robin?" Metal forks hit the sink. "Yes!?" my mom yells back. "Come up here, please! Quick! I need your help." My dad has never sounded so desperate. I assume he is splashing as he sometimes does, harmless enough but a sopping mess requiring extra hands and extra towels, of which we have plenty. We are running up the stairs: me, my mom, my two younger brothers, a blur of brothers in their bright colored PJ pants. Thudding feet on hard wooden steps, we all turn at the landing, hands overlapping, the banister slipping from our fingertips. "Hurry!" I see my older brother. My mom stops halfway down the hall. Stock-still, she stares. "He's dead", she says. The bathwater slaps against the tile floor, the dull sound of pale blue skin writhing on the surface of the murky water. My mom has the tendency to cry over spilled milk, literal spilled milk, sticky on the shelves of the refrigerator. My brother spilling out of the bathtub, however, colorless and lifeless as a pool of milk, evokes only a quiet metronome: "He's dead. He's dead." I scream as though he is. ~ My dad yanks my brother from the bathtub, a misguided hairbrush wedged between his teeth and tongue, not knowing any better at the time. He grasps his arms to keep him from bashing his head on any corners. Grasping, his voice sounds full of bathwater. My mom calls an ambulance, not for the first time, but for a seizure, the first and the only. A side effect of a side effect, a drug to combat seizures. A side effect of an antipsychotic; this strikes me as psychotic. I scream a blood-curdling scream. I stand there. I stand there, and I scream. This is the memory, the images that seize me. There is a before, but no after, except... he is not dead. His skin must fade from blue to white, but I cannot tell you when. I am eleven. ~ Intricate mazes and elaborate structures, four foot buildings made of interlocking plastic tubes; an autistic child's abstract art that stretches from the bathroom to the bedroom, and all the way down the hall. Tinker Toys are a mass of bright yellow wheels, pink and green straws and various pieces that fit together to create swing-sets, wind-mills, et cetera. Kieri spends hours connecting the parts, no reference to instruction manuals. The toy sculptures look like playground equipment for beautiful insects or birds. As kids, we don't think much of them; they are toys. We weave through the structures casually, on our way to shower, brush our teeth. My mom however knows they are extraordinary; imaginative and significant. I find his creations both funny and sweet. Like any kid with an obsession, you search for appendages to affix to it, e.g., magnets. Magnetic balls and rods in translucent rainbow colors. It is the early 2000's. These balls and rods will create smaller, more symmetrical structures, though they will not stretch from room to room. He loves the magnets. He sits in his small bedroom in the attic, small enough to fit just a bed and a TV. You can't stand up inside this room. The floor beside the floor-bed is home to geometric floor-plans: magnetic squares and triangles and rectangles flat on the floor. Not as colorful or impressive as the Tinker Toys, but he builds in his room watching movies. He doesn't speak, but seems happy. My family is eating at The Great Dane Pub, downtown. Burgers, beer, smoking or non-smoking. My dad will proudly tell you he has never smoked a cigarette, but there is only room for seven in the smoking section. Kieri is sick, a stomach bug it seems; I'm nervous though, as he has barely touched his food in weeks, and his skin is pale and clammy. Tonight seems especially bad; he won't touch his beloved French Fries. At home that night, in my all blue bedroom, I hear him throwing up. I run up the carpeted steps to the attic. Staring into the toilet bowl, bobbing there, I see a bright orange wooden carrot. "Oh my god", I say. Oh my god. See, I can connect things too. My youngest brother Atticus is six, and in his room he has a small tin can of wooden peas and carrots. Kieri must have swallowed them, thinking they were food, and this is why he's sick! I tell my parents, like a boastful detective, and they leave the house at once. My mom and dad are at the Emergency Room with Kieri. We stretch out on their queen-sized bed at home and watch reality shows. It's fun, as we cradle the phone and wait for answers. "The X-ray lit up like a Christmas tree. He swallowed eighteen magnetic rods, Antigone. Thirty-six magnets total. The technicians swarmed around the screen with their jaws on the floor. They had never seen anything like it." He lays there enveloped in the pale green hospital gown, twenty pounds lighter than two weeks prior. The magnets were connecting from intestine to intestine, creating holes, so parts of the intestine were removed entirely. My dad sleeps to the right of him in the hospital room, never leaving his side. One night, he abruptly awakens. Kieri sits up straight in bed, and dangling from his little wrist, he grips his nasogastric catheter. My dad immediately calls for the nurse, the tube hanging there limply, not unlike a Tinker Toy. He pulled it from his nostril like he pulled tubes from the sockets of blue and yellow plastic wheels. I can see the intricate structures glowing inside him. I can see him lit up like a Christmas tree. I can see his luminescent skin, glowing in the dark. The scar is thick, runs all the way down his stomach, like a route on a map, but ragged and protruding. When the stitches have been taken out, I touch his scar, so gently. I don't know who I worry it will hurt. Him? Or me? Discharged from the hospital, they send us home with a plastic jar; in it, a single cloudy magnet, a blackened fragment of my brother's intestine. I open it once, drawn to this dark inner material, this thing with holes, and it smells like death. He is fourteen years old. The doctors are shocked he lived through it. ~ We are downstairs. I am cocooned in the summer afternoon, convalescing after a long hot day at the public pool, in the nook of a brown leather armchair. We are scattered in the shadowy room, sleepily watching reruns on TV. There is an apple pie pancake in the microwave; a daily treat, followed by a bowl of Ramen. Or maybe it's the Springtime. Maybe we come in with the groceries, bags and bags of crinkling white plastic. They are planted in the mud room, then transferred to the kitchen floor, eventually being swallowed by the large black fridge, my mom bent at the waist hoisting gallon after gallon of milk onto the counter. "Robin?" My mom is a wide-eyed bird, platinum blonde hair growing like a Polish Chicken. She bobs her head around the corner. "Yes?" "Can you come up here please", my dad sounds calm and cool, as usual, beckoning from the top of the staircase. I don't remember the day or the season, Monday or Friday, Spring or Fall. But he does fall, my dad does, onto the sharp corner of a wooden desk, and he splits his head down the middle. ~ The Risperdal is for the violence. It started with a soft punch, sitting on the pavement at the bus stop, pulling grass from the sidewalk cracks, after a day of summer camp. We had picked him up in the afternoon, Skye and I, and it took us a while to get him home. Maybe he was impatient, or hot, or annoyed at our wise-cracks, but Kieri punched Skye in the arm. It was the first time, so the shock of it was funny. We laughed so hard we almost cried. After that it happened often; water dumped on our heads out of Dixie cups, metal forks thrown on the floor if we were lucky. Then things escalated. My hair was pulled and left like a nest in the backseat of the minivan; we were kicked, punched, chased and shoved. My dad split his head down the middle. Whisper it all, I could have sworn they had called it, discussing medication. Supposed to help with violence and aggression, said the doctors. ~ "Robin? Can you come up here, please?" We find my dad lying on the hardwood floor, woven hands a cradle for his newly balding head. Dark blood pools around him in a halo. "I hit my head. On the corner of the desk", my dad grunts in a staccato. "Kier kicked me and I lost my balance. Does it look okay? Can someone check on Kier." My mom says nothing; silently steps around his head en route to the bedroom. I do not even hear her footsteps, flip-flops smacking the hard-wood. "MOM!" my oldest brother yells. He thinks she is checking on the furniture. We are all on edge. I think so too, the eerie calm of both of them unsettling. My mom pulls the landline from its cradle. ~ My dad sits at the head of the table, a half-smirk, hands folded. We stand behind and look at all the staples, counting the rungs of a ladder that now descend his Parietal bone. "Jeeesus", I grimace, looking closer. ~ 2023: My feet cause me pain. Depressed for months, my sore feet walk me, apprehensively, to the Podiatrist's office on Damen. Two weeks later I lay shivering beneath a swarm of faces with an IV in my wrist. At four foot eleven, the hospital gown skims my ankles. "Put your foot right here, Hun", the kind surgeon tells me. Someone then covers me with a heated white blanket. When I open my eyes my appendage is numb, wrapped and wrapped in a bandage. The hard part for me is the waiting. Waiting for my foot to heal. Waiting for my brother to be okay. Waiting to hear bad news. We wait for his budget to be approved, so he can move into a care home. And I never thought it would come to this. I would not let it happen. We would always take care of Kieri. And if he couldn't live at home he would come and live with me. Always and forever. But my parents are older, 65 and 67, and Kieri is stronger, though we still help him with his birthday candles; all 31 of them. I prop my foot up but it throbs. 2022: I go home for Christmas and it's quite the ordeal. Thirty-five below zero, with windchill, it is an echo of the Polar Vortex years prior. I am a pair of foggy glasses floating on the Blue Line, the rest of me swallowed up in Nylon and Wool. I have a large bag of presents I can finally afford, and a small bag with just a sweater and a toothbrush. I take the train to O'hare and then the bus to Madison and then my mom's tiny car to the house. “Can I say hi to Kieri?” I wish I did not have to ask. Last summer is when the aggression returned. It comes in waves, crashing. “Bye Kier”, means I better leave, in Echolalia. “Stay”, means I can sit, and I do. I tell no one that he lightly shoves me; a warning sign, a ripple. I was sad I couldn’t make it on summer vacation. I thought I would have gotten to see Kieri swim. But it turned out that no, I would not have, because that summer he did not swim. “It’s not as bad as it used to be though, is it?” I text my mom from work. “Like hitting wise? ‘Cause I just worry ‘cause Dad is older and can’t really afford to be like, knocked around by Kieri like he used to be. I just worry about that.” The living room is warm and electric, everything lit up by the Christmas tree in the corner. Atticus and I are laughing, eating. The TV is on but it buffers. Then I hear stomping. The whole house shakes. This time it is not the sizzling old radiator. The Tardive Dyskinesia keeps him stuck in one place; a side effect of a side effect, a body that must keep moving; something akin to, yet the polar opposite, of drug-induced Parkinsonism. His feet tramp between the creaky floorboards, for minutes, sometimes hours. The same spot, in the same room, sweating, breathless. I see his small pale body swimming. The stomping grows louder and louder. “You are NOT going to do this. YOU ARE NOT. GOING. TO DO THIS!” I hear my dad’s gravelly cry whose meaning I have come to instantly distinguish. “Yes I worry about him. I was saying to him earlier that it is a very scary thing to watch with him at this age. Not to worry you more but it is just a tough thing.”, my mom texts back. Kieri is extremely ramped up, pure force. He is small, but strong, like my dad is. My dad is nearing seventy and limping. My dad falls flat on his back, shielding himself with a large white pillow, my brother shrieking as he pins him to the ground. It all happens in an instant. Once again my voice is useless. My small arms rush toward them but do nothing. I run my hands through my hair, something wedged deep in my throat. I try not to bite my own tongue. The image of him being thrown against the hardwood plays over and over in my head, on a loop. I am shocked his head is intact. My dad and brother dance and sway; two magnets changing polarity. “When push comes to hug”, my dad calls this. I stand there, as I do ten and twenty years prior, a child again, but not really. Then I fall to the floor in the kitchen in tears, questioning time entirely. "This can't happen anymore!" I yell to my mom, who stands there, looking small and tired. "I know," she says. "He is going to kill him." Everyone looks so small, like they are floating on Oval Beach past the buoys. I am stranded there afraid of the water. The closer they are the harder they are to recall, my memories seizing in murky water. They wash up white and frothing at the shore. “Shhh” the pictures whisper. Then they suck back into the glittering deep. All you see is a dark wet outline; who you used to be. 2012: I hear Kieri’s soft yet heavy footsteps in the hallway. "Alright, Buddy", means my dad has drained the tub, brushed his teeth, patted him dry with powder. My bedroom door creaks open slightly and I see his sweet face peeking through the crack, clean shaven face and wet hair combed back in a ducktail. “Hey, Buddy!” I invite him in. “Hey, Buddy”, he echoes, shyly approaching me at my desk. He looks around curiously before pointing a finger at my iPhone 1, the black faux-alligator phone case. “I want dis one”, he says, meaning my music. I laugh before I happily oblige. I plug in his headphones as he stares at the little black brick, green eyes hungry and longing. “What song do you want to listen to, Kieri Pie?” I show him the pictures of the different albums. “Addigator”, he says, so gently. Alligator, not referring to the phone case, but Alligator by Tegan And Sara, his favorite song at the moment. I hand him his ear buds and he slips one in each ear, then walks away satisfied as the song leaks out behind him. Today: Yesterday was my birthday, the fifth of July. The evening was cool but mosquitoes aplenty, bickering over my thighs and arms. Every year I swat at clouds of bugs and sparks of fire, festively encroaching on my special day. Today I long to lay in the sun, swathed in a fine white blanket of sand. I take a warm and empty bus too early for most. The sunlight streaks the deep blue seats. I want to hear the water at my ankles, a good thirty feet from getting wet, up in the dunes with the beach grass, which I will twiddle in my fingers like a dream. The Risperdal took a piece of him we will never get back. He doesn’t ask for music very often. Weaning him off it, we were told it would be something akin to Heroin withdrawal. He sat in a closet of a room, anything larger too stimulating. His skin looked wet and white and his eyes were glazed and begging. His hair grew long and his body thinner. It killed me but I couldn’t stop looking. There were two modes, both terrible: violent, or worse, catatonic. The Risperdal took a piece of me I will never get back; left something darkened with holes, that whispers. The beach is empty save for the necessary man and dog and Seagulls, dispersed amidst the trash, heads shining like those tiny white shells that slip, so subtly, through your fingers. I lay down. I breathe as does the sediment, cold waves coursing through me. The rocks and I are rocked to a place that is close but not quite sleep. My feet are hot and bare and dry, nerves tingling in my toes before they float above me. I close my eyes and see nothing... but smooth, red lines. ~ A dream I had, that really happened: Run around on me, sooner die without, run around on me, di-ie without Over you, over you, over youuu He charges ahead to the song, eyes wide with pure excitement, pacing the length of the dining room table. He dances in this fervent manner until his body drips with sweat. He turns on his heel in the opposite direction, legs pounding the floor with every step, my small black phone in the palm of his hand. The glass centerpiece tinkles as the table shakes. My heart in its vase clinks against it. I laugh so hard I almost cry, as I stand there- Always watching. Antigone Gamble is an artist living in Chicago, Il. She spends her time reading, drawing and writing or hanging with her two beautiful circus kitties, Matilda and Stella. She is drawn to the imperfect beauty of every day life and stories of perseverance. 7/29/2023 Side Effects by Brenna Cameronminka6 CC

Side Effects “I shouldn’t even say this.” Mom looks at me, tears in her eyes. We’ve alternated the entire weekend of who has tears in their eyes. Whose turn it is to cry. It’s her turn. “Do you know what I’m going to say?” I shake my head no. She takes a sip of her wine. She’s the one who suggested we get a drink after we drove away from the hospital. A building tucked into suburbia. Off the highway where just minutes before there were only corn fields and oil rigs. It’s different than anywhere else my sister’s been before. A hospital not meant for patients with IVs or breathing tubes, but something more sinister, something you can’t always see. It’s a place where all the handles are smooth and patients’ bags are checked for metal-containing bras, drawstrings on pants and jackets. “To keep everyone safe,” the nurse explained to us as we dropped a bag of my sister’s clothes off at the front door. The bourbon burns my throat, taking away the sour taste in my stomach. “Sometimes I question whether all of this was worth it,” Mom says now, taking a sip of her wine. “Should we be treating these kids if this is what they’re up against?” I nod. “I think about it nearly every day.” That is, every day since Caitlin became sick again. We were twelve when she was diagnosed with brain cancer. She survived, but just barely. It took her gallbladder and her adrenal gland. It destroyed her pituitary’s ability to make any hormones. It all seemed like acceptable trade-offs at first. The biggest worry she had were the scars the size of little fists on her chest and abdomen – she didn’t want to wear a bikini. And the lack of hormones meant she hadn’t gotten her period, which for my sister—the perpetual tomboy—was at first a relief, and then when everyone else had her period, something she asked the doctor if it wasn’t just something they could get going already. But more than that it made her brain slow so instead of taking fifteen minutes to study for the upcoming Spanish quiz, she took an hour. It made it so driving was nearly impossible—the process of deciding which lane to be in, checking the side mirror while also keeping the car straight, realizing that you needed to speed up to merge—too much for her to handle. And then there was her coordination, which was never quite the same afterwards. Instead of becoming the star soccer player of the high school team – which by all means she was slated to be when she was ten years old, a dribbling, athletic fiend – she barely made the freshman team. Her run was now awkward and tilted. Just a year later, she quit. “It’s not the same,” she admitted. “I’ll never be what I once was.” We were the same age – triplets – and yet, it became clearer as we grew up that her development was forever arrested as a thirteen-year-old girl. When we graduated college, she moved back in with our Mom, while Pierce and I moved abroad – me to Thailand, and Pierce to Central America. I went to medical school. Pierce started a business. And Caitlin, she wanted so much for herself – to go back to school and get her master’s, to move out, to be independent – and for reasons that she couldn’t understand, these goals were not entirely obtainable. And then, when we were twenty-eight years old, she became sick again. It was Thanksgiving. Her speech began to slur, and I – a third year medical student at the time – thought it was a stroke. Her neuro exam, though, was fine and so we waited a day to take her to the emergency room, where they did an MRI. There was a turkey in the oven at home because my mother, a perpetual holiday freak, wanted another full Thanksgiving dinner on Black Friday. The doctor came in, sitting down on a stool and as he said the words out loud – “There’s a lesion in your speech center” – it didn’t quite register that this would start her cycle of illness all over again. For months she had tests and imaging, everyone too scared to go into her brain and take whatever it was out. To obtain a level of certainty. It was either cancer – a different kind this time – or demyelination—the nerves in her central nervous system being stripped of their protective sheathing. Either way, both would be from the radiation she received to cure her the first time. The diagnosis only became clear as she declined. She started falling more, tripping over herself and falling down the stairs. And then, over the course of a single weekend, she could suddenly no longer sit up on her own. She couldn’t dress herself or go to the bathroom. That was when the doctors could say with certainty that this was demyelination. A type of MS, they said, because they didn’t know how else to explain it. At first, we all felt relief. It wasn’t cancer. But this was another type of torture. A slow death. It wouldn’t take her in a year but eventually, it would kill her. They placed a central line in her neck, the catheters taped to her skin so she could only sleep on one side. She got better in some ways – able to sit and stand and walk again. But there were small changes, her brain slowly being eaten away, little chunks of grey matter disappearing, so small that the MRI could barely pick it up – just little blips of flare. They go into the emergency room on Friday for a sore throat, my mother calling me on my work break to inform me, but also to ask my opinion. Despite my mother being a nurse, we have now officially transitioned roles. I am the medical confidant. The advisor. The one who reads and interprets the MRI scans for everyone in the family. Who breaks down the treatments and the research. It’s a role I take on with trepidation. It’s odd still, to be the one who knows the most. I want to know less. For reasons I can’t explain then, I have a terrible feeling. It’s just a sore throat, I tell myself. But an hour later, when my mom calls back to give me an update she whispers into the phone: “Brenna, she says she’s suicidal.” It’s not entirely a surprise. She’s had these thoughts before. But when the psychiatrist sees her, Caitlin, unbeknownst to all of us, says she has a plan to kill herself. The psychiatrist recommends inpatient psych treatment. They take her clothes, giving her a pair of scrubs instead that I swear are made from a fine plastic, not even a thread of cotton holding them together. “I know she wasn’t happy,” I tell my mother now, taking a sip of my wine. “But I didn’t realize just how unhappy she was. What she was willing to do.” “I don’t know that she would have done any of those things,” Mom says. She taps her finger against the wood grain of the table. I nod. Although I’m not so sure. I don’t know what to believe. We talk about how anyone in Caitlin’s position would feel the way she does. Lost and alone. And stuck. Completely stuck. “She’s thirty,” my mom says. “Thirty years old.” “And she can’t drive. Can barely work. She lives with her mom.” “She has no friends,” Mom adds. I nod. Cancer has taken away so much. Her brain was never quite normal after all the radiation—when they did it, they had her face down on a table, a custom-made cage screwed over the back of her head, so they knew just where to aim the protons – but now her white matter is crumbling. And if her brain can’t fire well enough to keep her upright going down a set of stairs then it’s no wonder that it’s hard to convince herself to want to be alive. It’s no wonder that her brain is sick in more ways than one. She is suffering a long, slow death and there is nothing I can do but love her. She is not alone. Childhood cancer forces toxic chemicals into a growing body. A growing brain. The rates of cure have increased astronomically – a child diagnosed with leukemia now has a 90% chance of survival. But these numbers fail to encompass everything that comes afterwards. The decade later where their brains begin to crumble, where second cancers set in, and it becomes glaringly obvious that they will never be a normal adult. It’s not everyone but it certainly isn’t just Caitlin. “We’ll look back ten years from now and think how good we had it then,” Mom says, taking the final sip of wine. I shiver. Despite my jacket, I’m not used to the autumn chill. “Ten years,” I repeat, unable to hide my surprise. My distaste. “In ten years, I hope—” I hesitate, fingering the stem of my wine glass. “In ten years, I hope she’s dead.” Now it’s my turn to cry. “I don’t think she will be.” It’s the saddest thing I’ve heard all day. Brenna Cameron is an emerging writer and a pediatrician living in Denver. Her fiction and poetry have previously been published in Please See Me, Vessel Arts Magazine, The Human Touch, and Cross Currents. In her free time you can find her playing in the Rocky Mountains with her dog Rowan. minka6 CC

How to Age Gracefully: Five Shorts 1. My date tells me she was in prison for check fraud. It’s not as uncommon as it sounds, she says. I still can’t vote. Twenty minutes ago, we were at a small gathering at a record shop, where an open buffet sent the stink of cheese and onions through the oncoming summer air. She left me with her friends to climb on top of her red Mustang outside, where people took photos of her stretched out on the rooftop, hair swinging, legs splayed, her nose ring glinting in the sun. Now, we sit across from each other in a Thai restaurant down the street. It is pre-COVID in Florida and there are no barriers between the booths. Music tinkles in the background, barely audible. I chew on a spring roll, unbothered. In my mind, this still could be something, regardless of her leaving me with her friends earlier. We have a spark. A connection. This is how I approach all dates at this age: with endless possibility. You should be able to vote, I tell her. That’s messed up. Our sushi comes out. I eat two full rolls without worrying if the sodium in the soy sauce will make me bloat in the morning or if something in the fish might make me sick later that evening. I’m not scared of her breaking my heart or saying something that will shake me so deeply I start questioning if people even care for one another anymore. I am twenty-seven. She is thirty-five. I really like you, she says. Where do you want to go after this? 2. My date in Massachusetts is a dark-haired version of Laura Dern in Jurassic Park. She wears cargo pants and tucks her hair back in a clip, small strands of grey weaving along her hairline. We drive to a park where the pines and oaks are draped with multicolored lights, a carousel bobbing over a coat of snow. There are no palm trees, no sunlight. She drives us around in an old Jeep that’s black and crusted white at the bottom from snow and salt. This is a strange place to live, she admits. It’s like everyone is testing me, I tell her. Because I’m not from here. It took ten years for me to fit in, she replies. We stop at the carousel, and she cajoles me into climbing on. It’s cold enough that I shiver under my winter coat, my throat tight with nausea. It’s been pushing at the base of my throat since I met her, under the lamplight of my small house, the driveway still unplowed and tinted with dirty snow. It’s not the snow I was seeking when I moved here, the soft powered kind that shimmers in the light. This snow is hard and crusted and sharp. See? she asks. It’s fun. It is fun, but it’s hard to enjoy that fun when you’re nauseous. I’m nauseous because certain foods make me sick now, even though they never used to. I’m nauseous because I’m getting age spots on my shins and wrinkles around my eyes. Because it’s my seventh month in Massachusetts and things are still not settling well. My novel hasn’t sold. My coworkers are openly hostile. The cold is hard and unfriendly; it keeps me inside, curled up on my couch, trying to stay warm. Each night I go to bed with this terrible feeling that things are closer to the end now than they are to the beginning. Let’s go salsa dancing next time, the Laura Dern date says when she drops me off. I am thirty-two. She is forty-nine. We never do go dancing. 3. After our food, I ask red Mustang girl to take me home. Are you sure? she asks. We could go downtown and get tea. I consider. The light is still up outside, cresting over the Gulf. In minutes, the sunset colors will take the sky. Heat hovers over the pavement. It’s that part of summer where it’s just plain hot but not yet unbearably so, the type of Florida heat that is wet and thick as water. Tough to live with, but so beautiful. What kind of tea? I ask. Any kind you want, baby. I am curious, my attention piqued. We might go for tea and discover we both have a passion for traveling. We might accidentally catch the tail end of a jazz band – the jazz bar is right down the corner. We might bump into a new or old friend, or stumble upon a hundred dollars lying in the street, or some other wonderful thing I haven’t yet dreamed up. Nothing caffeinated, I say. It’s getting late. She tells me she knows a place, and then we climb into her car and engine growl down Central Ave, palm trees waving in an early summer breeze around us, windows down, the smell of the Florida sun on our lips, laughing to reggaeton music like we are much younger than we are. 4. At the start of my first Massachusetts spring, I go on a friend-date with a coworker six inches shorter than me. She wears a purple shirt and vest, her hair pulled back in a claw, spilling around the sides. The weather is almost in the seventies – unusual for this area and time – the sun shining undeterred and the wet, cold humidity that plagued the air throughout the winter is gone. Things feel positive for the first time in many, many months as we stroll around Northampton before tucking into a dark booth for dinner. Halfway through, I get a call with a new job offer. Everything is working out, my friend tells me. See? The next week, we cruise around thrift stores and then run errands together. We trade gifts, sit in the sunshine, laugh at dumb jokes from the front seat of her car. We make plans to do more things – go to her lake house, meet her sister, spend time with her son. I’m scared I grew up to be ordinary, I tell her one afternoon, perched on my couch with the television on. You’re far from it, she replies. I write a novella about people doing awful things to one another, partially inspired by the horrible things we witnessed at work that winter. She reads each chapter one by one as I finish them. I liked this, she texts. Or: this one was really good. The cold continues to ebb. We both move into better jobs. I am hopeful, but not like I used to be. She is fifty-three. I am thirty-three. By summer, our friendship fades: I never get to meet her sister or go to her lake house. 5. In the summer, tired and dateless, I go on long walks around the reservoir near my house in Western Massachusetts, stroll down the streets of my neighborhood saying hi to fenced in dogs, taking pictures of the tree blooms as they grow bigger and bigger. I break up with my writing agent, pluck weeds from the cool, wet earth in my yard. At night, I cry in my living room because time is moving so fast and it feels like I’m stuck here, not doing the things I always wanted to do, not being the person I always hoped I could be. There’s so much I’m not sure I can accomplish anymore, I tell a friend. I finish the novella and send it to publishers, trying to figure out who to dedicate it to. For the state of Massachusetts, I write as a test on my computer, just to see how it looks. You haven’t killed me yet, you fuck. But as much as I want to blame this all on the move, it’s not the state’s fault. My date with the red Mustang would be forty now. The last time I saw her on Instagram, she was in a committed relationship, pictures of their child propped on her lap, her nose ring gone, and I thought: What happened to her? Does she still have the Mustang? Does she still model from the rooftop of cars? Does she remember the date when we drove down Central with the windows wide and the engine roaring like everything was good and free and possible? Chelsea Catherine has lived and worked all over the country. They won the Mary C Mohr award for nonfiction through the Southern Indiana Review and their second book, Summer of the Cicadas, won the Quill Prose Award from Red Hen Press. In 2022, they spent a month in Alaska at the Alderworks Artists Retreat and their story, The Not-Deer, was recently published in an anthology out of London. Their work can be found in Hobart, Passengers Journal, The Florida Review, and others. 7/29/2023 Therapy by Janelle CorderoSarah C Murray CC

Therapy I. It’s not your fault, my therapist says. I look out the window as a homeless man walks by, shirtless and sunburned, cargo pants sagging from the sharp bones of his pelvis, blonde dreadlocks knotted at the nape of his neck, two or three inches of grow-out at the roots. You’re a different person than you were eight years ago, she says, and so is he. My husband, she means. I sigh and turn back to face her, this woman who has known me less than a year, who has yet to see me cry or get angry in her office on the first floor of a 1900s Victorian in Browne’s Addition. I know more than you, I want to say, but what good would that do? So I just nod for the next half hour, tell her she’s right about everything. And then I leave, unchanged, rain falling on my face as I walk to the car. II. Coral light on wet pavement this morning, like how it is in the summer when all the forests are burning and smoke surrounds the city. I’m thinking of firing my therapist because I can’t tell her the truth. You fall in love too easily, my friend said after learning I’m a Pisces. I’m in love with everyone except myself. A train carves through a field of yellow flowers up north, pine-covered mountains in the distance—early yet, but all of it will go up in flames. III. The white sheets fall from the clothesline and get all twisted up on the lawn like an unmade bed. Peonies open beneath the pine tree, and my husband says they look like labia, the thrush and curl of dark pink petals, wet with dew. I ignore the laundry and lift one of the flowers, its bloom as big as my face. I inhale and taste a fleeting sweetness at the back of my throat. IV. What is meant for me? I walk the dirt road with my mother, past the pond with ducks and coots and geese churning the water, cows standing at the shallow edges trying to stay cool in the heat. Past the wild rose bushes, bright green swaths of farmland, hilltop houses with metal roofs and chicken coops in the backyard. My mother says she walked to the hospital on the day my brother was born because she had an appointment. Any time now, the doctor said, and sent her home. She was back four hours later with labor pains. She worked until the day I was born, teaching business classes to single moms, high school students and recovering addicts at the community college. Even so, she only took a few weeks off afterwards, eager to return to that world where she could lift a finger to her lips and the whole room would go quiet, waiting for her to speak. I want to ask if she’s ever miscarried, but I have a feeling the answer is no. Mom, I want to say, I’m worried about everything. But there are birds in my throat, white doves, so I say nothing. V. Someone rings the doorbell at the worst time. We’re fighting in the kitchen, and when the bell tolls we both go quiet. I’m crying, so no way in hell am I answering the door. My husband hesitates before turning, walking away. Just a neighbor wanting to shoot the shit, that’s all. He leans in the doorframe and talks shop with the neighbor for a few minutes before saying sorry, gotta go—dinner’s almost ready. I’m done crying by the time he comes back. I’m done with the whole damn night. My husband reaches for me and I want it, his arms around my waist, my tear-stained cheek pressed against his shoulder, sadness hanging above us like smoke from whatever is burning on the stovetop, whatever we’ve forgotten. Janelle Cordero is an interdisciplinary artist and educator living in Spokane, WA. Her writing has been published in dozens of literary journals, including Harpur Palate, Autofocus and Hobart, while her paintings have been featured in venues throughout the Pacific Northwest. Janelle is the author of four books of poetry, including Impossible Years (Vegetarian Alcoholic Press, 2022). Stay connected with Janelle's work at www.janellecordero.com and follow her on Instagram @janelle_v_cordero. |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

April 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed