|

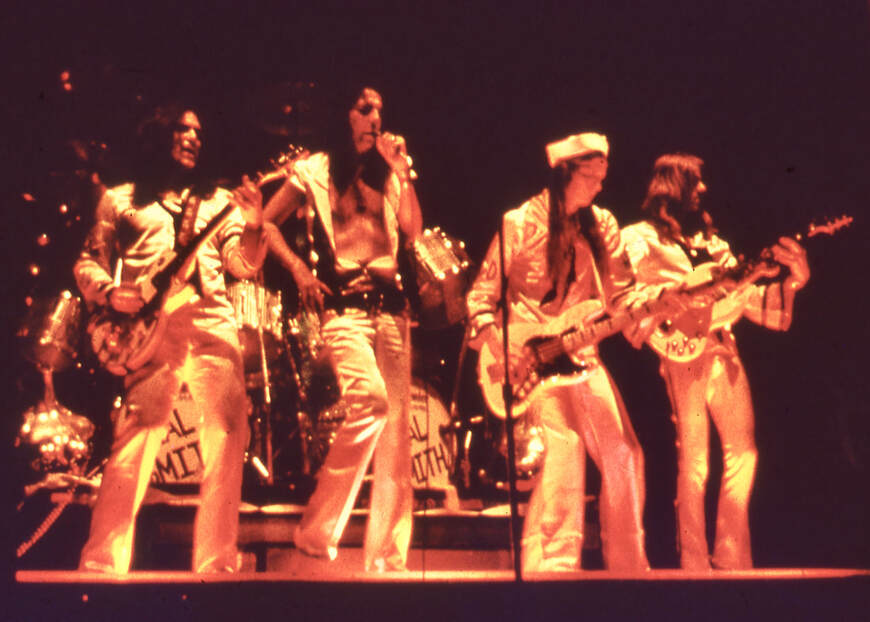

11/30/2021 Alice’s Arm by Paul Ruta Alice’s Arm I didn’t get weird about Alice’s Arm until it went missing. It was special. In fact, in all my decades of going to concerts, Alice’s Arm is the only physical souvenir I ever got. It was a little something thrown to me from the stage – a piece of crap, if you asked my mom, the prime suspect in its eventual disappearance, but a relic of Roman proportions to me. By late 1973 I was a newly licensed driver, and my friends and I would pile into the Volkswagen and cross the border from Niagara Falls to see concerts in Buffalo, New York. The venue was often Memorial Auditorium – the Odd, as it was known – a cavernous facility noted for its cruel acoustics. Alice Cooper played the Odd that New Year’s Eve, the final North American date on the Billion Dollar Babies tour. You got your money’s worth with Alice. He believed that showmanship was equally important as musicianship – a radical concept in the early seventies – and he pioneered the idea of rock concert as multimedia extravaganza. Alice Cooper was massively popular at the time, though his act was macabre: blood-filled and violent. At a certain point a guillotine was revealed onstage, whereupon Alice chopped the head off a mannequin, dismembered its body and flung the parts into the audience. I happened to catch one of those parts. It was a pink flesh-toned curve of fiberglas, an eight-inch fragment of the mannequin’s forearm. I was thrilled. I kept Alice’s Arm in a dresser drawer, nestled alongside a barrette taken from an early girlfriend, a clip-on bowtie, a broken Timex and the world’s least valuable coin collection. As with some of my other keepsakes, especially the barrette, I would take Alice’s Arm out of the drawer from time to time, ponder it for a minute or two, maybe give it a sniff, then put it back. And that would be that. A few years later I came home from university for a weekend and discovered the tragedy. My mom, in the process of “straightening up” my bedroom, had gone into my drawer and threw away Alice’s Arm. I didn’t see it this way back then, but she couldn’t have known its significance. Any reasonable, randomly selected adult would similarly conclude that Alice’s Arm looked exactly like a piece of crap and be inclined to throw it away. Still, she denied it, but I knew. If my mom hadn’t thrown it away, Alice’s Arm would probably have found its way, in the natural course of events, to the bottom of a trunk containing other boyhood mementos, then stashed in an attic and eventually be lost to the mists of time. But she did throw it away, and that has made all the difference. From the moment of its disappearance, Alice’s Arm took on new, mythological meaning. It passed from existence to nonexistence, from reality to immortality. Now I was free to openly mourn the loss of Alice’s Arm – its amputation from my life, no less. Now, according to my own melodramatic script, I was a victim of parental tyranny. I’d been emotionally trampled and couldn’t wait to have my suffering validated, especially by my fellow sufferers. Suddenly I was potentially interesting among a certain subset of my peers, or at least somewhat less uninteresting than before. I thought so, anyway. It didn’t take long for me to snap out of my self-imposed victimhood, especially when I began to appreciate that more than a few people I knew suffered from problems that were not imaginary, not self-imposed. Yes, some people had real problems. And so, without further ado, Alice’s Arm was indeed quietly stowed away in a box of memories: the overstuffed one inside my head. Alice’s Arm continues to occupy a strange little corner of my mind, and like a resident ghost it occasionally rattles its chains just enough to remind me it’s still up there. So here I am, nearly half a century later, yammering on about it yet again. I suppose that’s how fetishes work. I once read about a neuropsychological study that said our personal, experiential memories are not as reliable as we like to think. The study wasn’t talking about the wobbly memories that we freely admit are flawed, but the ones we believe we remember with great clarity. The thrust of it is that the more we convince ourselves of our ability to zoom in and focus on the fractals of even our strongest, most detailed memories, the more inaccurate our recall actually is. Further, that the more often we conjure a given memory, the worse it gets, like a tracing of a tracing of a tracing, until we’re left with little more than a mnemonic emoji that we mistake for the real thing. Many people would call bullshit on that study, which, in a way, proves its point. I haven’t decided one way or the other. All I know is that there’s nothing more mysterious to us humans than the workings of our own brains, so maybe there’s some deep evolutionary purpose for the way our minds keep messing with us. I hope that study is wrong, if only for selfish reasons. I want to believe that in my mind I can truly sense the grapefruit-like heft of Alice’s Arm and hear the dull response to my tapping fingernail, I want to feel the finely pebbled texture of its spray-painted exterior and stroke its rougher concave insides, and I want to smell the peculiar odor of its odorlessness. If it turns out that my memory of Alice’s Arm is somehow not accurate, or not entirely accurate, so be it. Anyway, how would I know? The memory is close enough for rock & roll and that’s good enough for me.  Paul Ruta is a Canadian writer living in Hong Kong with his wife and a geriatric tabby called Zazu; his kids live on Zoom. Recent work appears in Cheap Pop, F(r)iction, Reflex Press, Truffle, Ghost Parachute and Smithsonian Magazine. He reads for No Contact magazine. @paulruta • paulthomasruta.com Comments are closed.

|

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

April 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed