|

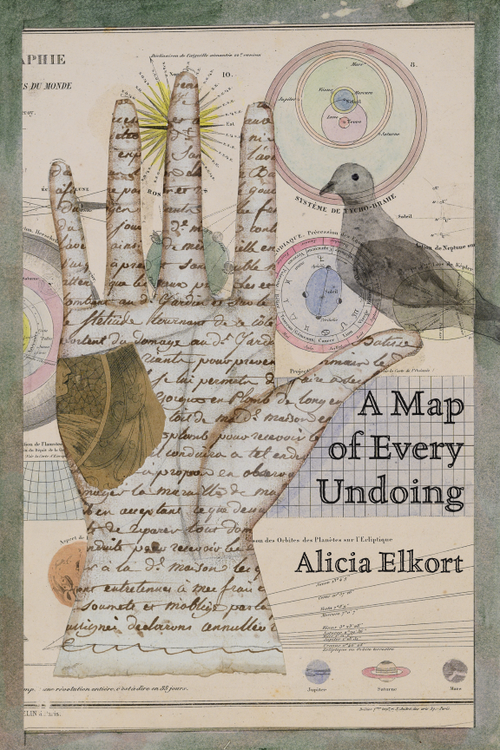

3/19/2023 An Interview with Alicia ElkortIn A Map of Every Undoing Alicia Elkort takes readers into the very heart of shatter and repair. One is changed, if ever so subtly, after one's journey through this remarkable book of poems. For trauma survivors, such writing and reading is a writing and reading back into life. Elkort has woven together a very precious and pained map toward self-repair, a place for all emotions to have their say. The abuser's injunction to silence here is broken open. To speak the unspeakable means that we did not die. Having survived, we must go on to show other's that there is life after "soul murder," and that that the shame we were given was never ours to begin with. As Alicia says; "to poem [our] darkness is to pull [our] shame into the light." Here, then, is a glimpse into that hard won journey towards light, the shedding of shame, and the reclamation of one's life. James Diaz: Can you tell us about the journey you've taken through A Map of Every Undoing? Alicia Elkort: I began writing poetry about twelve years ago. After a while, I took a few classes. In the beginning, I wrote poems that mostly had flowery endings. A friend, poet and writer Jenn Givhan, told me, wisely, to stop tying things up neatly with a bow at the end (forgive me for writing flowery epiphanies). Then I took a class on Duende. After the feedback on the first few poems, the instructor asked me if I could go darker. I thought to myself, “Oh you want dark, you have no freaking idea.” In essence she gave me permission, a permission that I hadn’t given myself. So, I wrote poems that were raw and painful. Until that time, I had been trying to keep that part of myself away from the public. I had so much shame around the childhood sexual trauma that I experienced and no idea that expressing the experiences holding the shame was acceptable, that I even could share that part of myself, who does that? When I poemed the darkness, I pulled the shame into the light where it began to lose its power over me. I began to invest the pain with meaning. It became an integral part of my healing journey. And then, as if that wasn’t enough, the response was revelatory. Others liked what I wrote. Others found meaning in what I wrote. Poems found publication. I got an email from a stranger thanking me for articulating what she was feeling. It helped, she said. Isn’t that pure gold? I am a huge fan of the memoirist Melissa Febos. She wrote an essay about making space in the room for this kind of writing, which has been deemed “confessional,” and therefore irrelevant in the larger scheme of art. Another way to dismiss women, for misogyny to gain footing. But craft is craft, no matter the subject. I found myself obsessed with expressing darkness in couplets, to lend them a lace-like feeling, to take the pain and craft something delicate, beautiful. I didn’t set out to write A Map of Every Undoing. Rather, at some point I found my title and then included the poems that had poured out of me once I gave myself permission and that also had resonance with the theme as prescribed by the title. It took a while for my book to find a home, and, in that time, I worked the poems again and again. And then when Stillhouse chose my book from a contest, Tommy Sheffield, my stunning editor, and I went through each poem, each line. JD: I imagine this cannot at all have been an easy book to write and move through, delving into childhood's many traumas and survival points. It takes great courage to return to the places where we were most wounded. From what place did you find shelter while working with these poems, whether in other poets, songs, films, meditation, long walks to a familiar bridge, what were the anchors for you on this journey? AE: There were tears. Lots of them. The 13th century Persian poet Rumi wrote “Out beyond ideas of wrongdoing and rightdoing, there is a field. I'll meet you there.” I had (and sadly continue to have) so many judgments about what I name/named my negative experiences. But if there exists a place, a consciousness where there is neither good nor bad, then what I am left with is the incandescence of being. A spiritual advisor I’ve followed says “remember to remember.” Right and wrong live in duality and exist on the egoic level. We each have a sage inside of us that can find and express wisdom. What I mean to say is that cultivating a consciousness of non-duality has helped me remember who I really am—an expression of infinite love. If that sounds airy fairy then so be it. But it’s what has helped me see that whatever I’ve experienced has not altered the essence of my being. And that is where I find solace. And to your point, the reminders to remember are everywhere: music, film, literature, poetry to name a few, and then most importantly for me, out in nature surrounded by trees, my happy place. JD: In one poem you write for all those girls who have suffered the greatest violence imaginable, taken too soon from this world by violence and a world that still sadly does not make enough room for girls to be heard and protected. What are your thoughts around this issue, and what do you hope people will take away from this book that will cause them to be more aware and proactive to the fraught lives of girls living in a world that does not do nearly enough to protect them? AE: For all those girls, I grieve. The tears are always there. I will cry for them; I will cry for you. I would hope my book would act as the knife in the poem you mention, a way out, a way to survive. All the girls mentioned in that poem committed suicide which I’ve learned is anger turned inside with no way out, no agency. I’d hope my book will in some way, no matter how small, give those who have suffered transgressions, a way out, a place to turn to, and by that I mean recognizing and integrating all the emotions that get us there—fear, loneliness, shame, sadness, anger, and for me, especially anger. I was told “good girls” don’t get angry, in school, at home, in the culture at large. The poem You Don’t Have to Be Good is about recognizing that my then five-year-old niece had access to an anger that I never could dream of expressing. I know anger unchecked can be destructive, but in the moment that I wrote about, I wanted to protect her ability to get angry, to say no. To have agency over her body. To scream bloody murder if she needed to. I wrote a Me Too poem when that movement was getting started. I was terrified to send it out. I did it anyway. Now I have my book, and if it can make a little more room in the world for the artistic expression of these stories, these lived experiences, then even better. Who gets to tell the story is a big part of misogyny. My little book existing in the world is helping to broaden the litmus for who gets to tell the story. As more and more of our stories are told, the shame around these experiences dissipates and awareness increases. And with awareness, the girl on the airplane being trafficked is rescued by an observant steward. The woman at the bar is informed someone spiked her drink by two people who were watching when she turned her head. And then, the kid in school who is struggling, we see them and support them. Once the damage is done, I would hope that my book says “Here’s how I worked through my darkness. Maybe it can help, maybe not. Either way, I see you. You are not alone. I recognize your pain, and you are beautiful.” Throughout my book, I’ve included poems that re-imagine common mythologies and usually they are re-imagined in ways that create agency for the female character. We tell the truth of Medusa. Little Red Riding Hood finds agency by befriending her inner wolf. Scheherazade realizes that her entire life has bought her to this moment where telling a story will save not only her life, but hundreds more. Again, who gets to tell the story and what world does it reflect? We are all sick of the tired, useless tropes where a woman or girl is rescued. When there is no one intervening, there is no rescue. No one rescued me, so as an adult I had to rescue myself. Katherine Hepburn famously said, “As one goes through life, one learns that if you don’t paddle your own canoe, you don’t move.” We rescue ourselves and then we share with others how we did it, how we continue to thrive after such horror. I do it in my poems and in my work as a Life Coach—assisting others in re-writing how the story ends. JD: I love how, in the beginning poem, you say: "I'm not there yet," in regard to being able to stand on the other side of the waters of all that happened. There is an immediacy in this work that announces that to remember will always be devastating. But like through a sidewalk crack, things bloom in our lives, too. Life meeting despair at the crossroads. Does poetry feel like the bloom-growth in impossible places? How do you harvest such hope in your own life? It's back and forth, isn't it? I know I've certainly found that to be the case in my own healing journey. Some days better than others. What helps on the not so better days? AE: Poetry is the bloom-growth in impossible places. I love that. I’d just shift it a little to say that for me, poetry has been the medium that nourished the bloom-growth in impossible places. 613 conditions must be met for me to feel safe to talk candidly about my experiences, meaning it hardly ever happens. But once the experience is in a poem, I have no problem sharing that. Once, after a reading, a woman came up to me, tears streaming down her face. She thanked me for giving her permission to feel the complex, opposing emotions around a traumatic experience. I cried with her. I couldn’t help but be moved by her vulnerability. Through poetry, through my poems, I have met some of the most wonderful people, and my life has been enriched. This is hope in action. In my work as a Life Coach, I am honored to witness bloom growth in those I work with. But really, I am lucky because to do this work, I must lift my vibration so that I can be of service. So, between coaching and poetry, I spend less time in despair than ever before. And still, it is a back and forth. Always. JD: What advice would you give to other writers who are struggling on their writer's path? What has helped you at those moments of stuck-ness or creative stalemate to continue to believe in and to cultivate the return of the life of words? AE: Support from other writers, other poets, first and foremost. When I get stuck, invariably one of my writer friends helps me un-stick by reminding me what we are doing here. I write and I heal, and I heal, and I write. For me, the alternative to this formula is unpleasant. It is important to recognize when our time is better spent resting and reflecting. Feeding the muse. But sometimes, all that’s needed is a strong cup of black tea to get the muse going. I read a quote a while ago that said something to the effect of, “The difference between those who do and those who don’t, is those who do, do.” If we spend too much time in self-doubt, we may look up and find we have missed the boat. JD: Any final words you'd like to offer, or projects coming up you would like to tell people about? AE: I am sending out my second book which is about the joy I experienced after the healing occurred. During the worst of it, joy seemed impossible, but here we are. When I was in 9th grade, I had a PE teacher who offered the most profound wisdom, probably unwittingly. We would come to the track in our green jumpsuits, and we’d moan and moan, “Aw gee, do we have to run laps?” She’d respond, “Oh no, you don’t have to run laps at all. You get to run laps.” I mean how wonderful is this life that we get to create and make art and channel our demons and our angels into poetry or writing or art or knitting or hiking, whatever brings us joy. We are the greatest alchemists of all time, we get to turn darkness into light, into art, into love. A Map of Every Undoing is now available from Stillhouse Press. Alicia Elkort is a poet, writer, and Life Coach. Her poems have been nominated thrice for the Pushcart, twice for Best of the Net and once for the Orisons Anthology, and her work has appeared in numerous journals and anthologies. She was born under the New Mexican sky and has returned to live amongst the juniper and pine where each day she is renewed by the still-life of blue and cloud. You can find out more about her coaching at Alicia Elkort Coaching. Comments are closed.

|

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

April 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed