|

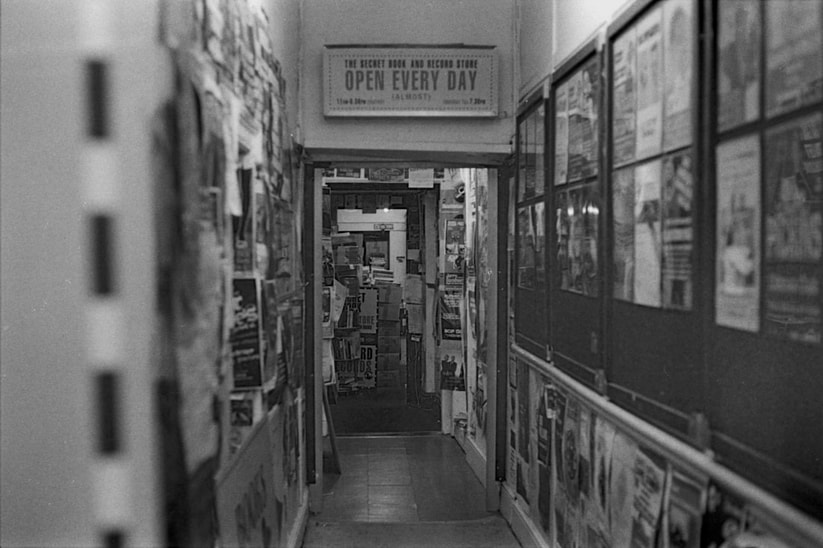

Follow PLAY > Apart from the usuals who wandered in and out to sift through old records the shop was unusually quiet. Marcel, the sales clerk, was leaning back on the brick wall behind the register, rolling a joint between his fingers. He took the fixings, rolled, licked, and twisted, then placed the cigarette in his mouth. The rose-colored tip glowed gold as his thumb stroked the wheel of the lighter, before browning, and turning black. He stared out the display window as he smoked. The evening sky was a pure, uninterrupted pink, and when the light autumn wind stirred there came through the open window the heavy scent of flowers from the market. Through the seam of smoke he could see the constant flicker of men and women passing by on the pavement – the shadows of birds fluttering in-between them. He had always been something of a daydreamer. He was used to standing by himself, staring into space, and thinking about nothing in particular – as if he really were the prey of aimless days. He turned away from the window after a while, noticing someone moving faintly in the periphery of his vision. His friend, Saoirse, was coming out one of the back rooms. She was carrying, in her arms, a stack of cardboard boxes filled with cassette tapes and vinyls. ‘Hey troublemaker,’ he said, watching as she put her boxes down on the carpeted floor to adjust the red bandana that was tying back her tight ringlets of greying-ginger hair. ‘Hey yourself,’ she smiled, stepping slowly out from the doorway. ‘They told me you collapsed.’ ‘I did,’ she said and a muted sunbeam cut through her hanging breath. ‘These legs of mine sure used to be a lot more cooperative back in the day.’ ‘Here,’ he took the joint from between his lips and extended it, ‘you wanna hit?’ ‘That’d be grand,’ she said before taking a small, slow draw. The paper crackled slightly as she inhaled. She was a sweet old lady – a little apple blossom from Ireland – and the shop belonged to her. She mostly dealt in second-hand vinyl though she also carried a selection of vintage instruments which had retained a certain charm through the years. The people who came to buy these were young mostly, hipsters and alike, manifesting nostalgia for times they had never actually lived. ‘I didn’t think you’d be, like, back on your feet so soon.’ ‘I’m not exactly the stay-in-bed type.’ ‘I know,’ he said, ‘but don’t you think you could be taking it, I don’t know, a little easier?’ ‘Ah now, it was only a light sprain.’ ‘I still think you should be resting.’ ‘And I think you shouldn’t be worryin’ about an old woman like me. There’s no sense in thinkin’ the worst, Marcel. It doesn’t help with anythin’ you know.’ ‘Yeah. You’re probably right.’ They passed the marijuana between them as they talked, shooting the breeze about one thing or another until there was nothing left but burnt-out ash and smoke receding into the air like ephemera. ‘I wanted to ask you something before you go,’ Saoirse said when it was time to close up. Marcel looked back over his shoulder. He had his hand on the door, ready to leave. ‘Earlier, as I came in, I saw you starin’ out the window there. What is it you were lookin’ at?’ Marcel waved goodbye as he left out the door, sounding the lintel over the mantle. ‘Looking out for what’s coming is all.’ ‘That’d be a fine thing,’ she said but Marcel had already gone. She frowned, revealing the valleys of her ageing face, ‘Too bad no one ever sees what’s coming.’ Marcel started toward the bus stop with his hands in his pockets, his feet falling against the pavement, the numbing air turning his breath to steam. >> FAST FORWARD >> The night was carrion black by the time he stepped off the bus and walked out onto the slick wet pavement. It was late after sunset but still far from dawn. He heard the doors shut behind him, then the bus pull away, it’s tail lights fleeting crimson into the distance, leaving him standing on the curb of the street – just a silhouette under the lemon streetlight. It had started to rain so he lifted his hood up over his head, walked to the crossing, pressed the button, and waited. Cars were running fast on both sides. He didn’t feel like going home, back to his small, empty apartment where all he seemed to do was cry. In that moment, as he waited for the red light to turn green, the only place he felt like going was somewhere loud enough to drown out his own thoughts. He noticed a bar on the other side of the street. It was a small place, set back from the main strip. Marcel walked in and let the door slam behind him. The place was a real dive – its walls were threadbare and everything seemed to be falling into dereliction. It looked like the kind of hauntingly vacant tableau people came to when sobriety started to feel too oppressive – too much like hard work – at least compared to the hollow lure of spirits and cordials. The same kind of people whose lives were so damn complicated they couldn’t stay on top of them in any meaningful way that didn’t make it look like their lives were just going to get more complicated. He tried hard not to think about that as he made his way to the bar and leaned against the counter but quickly found that trying not to think about a thing paradoxically only created a preoccupation with it. ‘Whiskey,’ he said, bringing out his wallet. ‘Sure,’ the bartender said in that not listening kind of a way. Marcel handed the guy a note and after a moment, the bartender slid his drink across the bar. He stared at his reflection in the bottom of the glass. He was a tall and lean twenty-something. His skin was the colour of pine and his face was obscured by disheveled black hair which bathed his deep set eyes in shadow. He stared for another second then finished his drink – tired to death of looking at his own reflection and hating what he saw. He wished, with each successive breath he took, that he could be someone else entirely; someone without so many insecurities. He had imagined, when he came in, that the loud music and drinking would have made him happy or at least have taken away some of the self-loathing that seemed to follow him everywhere he went like a vague smile, but he had been wrong. As he was considering getting up to leave, he noticed a man making his way over from the other side of the room to sit beside him at the bar. Even from the momentary glance Marcel caught of the man, he looked quite stunning. He was dressed in drag, his long hair lying over one shoulder of his short dress and all his features illuminated perfectly in the neon light from the bar. ‘A bird with one wing can’t fly, honey,’ the drag queen said, staring down at the empty glass between Marcel’s knuckles, ‘so how about I get you another drink?’ ‘I probably shouldn’t.’ Marcel said, shaking his head, suddenly very aware of himself. ‘One won’t hurt.’ ‘Is that what Eve said to Adam?’ The drag queen half smiled, full lips parting over perfect white teeth. He lifted his head to catch the bartender’s attention, ‘Two more whiskeys.’ ‘Thanks.’ Marcel said, receiving the drink when it came. ‘I’m wondering – do you often buy drinks for the strangers sitting across the bar from you?’ ‘Only the ones I can’t seem to take my eyes off.’ ‘I’m starting to think you might be trouble.’ ‘Well, you know what the trouble with trouble is?’ He leant forward to whisper in Marcel’s ear, ‘It’s actually a lot of fun!’ Marcel tried to suppress his grin, ‘What’s your name anyway?’ ‘Most people just call me Zizi. What about you?’ ‘Marcel.’ ‘Marcel,’ he repeated slowly, enunciating each syllable, turning the word over on his tongue, ‘that’s a sweet name. Were you named after the artist?’ ‘Marcel Duchamp. If you can call him an artist, then yeah, I was.’ ‘You don’t like him?’ ‘It’s not that I don’t like him exactly,’ Marcel paused, ‘I just don’t think he was all that. I mean, what’s so special about all the objects people take no notice of? Trust me. There’s nothing distinguished about neglected things.’ ‘I don’t know. I always thought there was something kind of poetic about the way he challenged people’s preconceptions – and if Picasso despised him then he must have been doing something right.’ ‘Sometimes I think he was just pulling a fast one on us, encouraging our capacity for illusion or our propensity to believe some things are more deserving of love than they actually are.’ ‘Oh honey, the man died half a century ago and we’re still talking about him. Even after all those years we’re still showing his art in galleries. That’s not an illusion.’ ‘I’m pretty sure you didn’t come all the way over here to talk about twentieth-century art.’ ‘You’re right, I didn’t. As much as I enjoy the avant-garde,’ he laughed, motioning at his drag, ‘I actually came over to see over to see if you were okay. You looked like you were having a rough night.’ ‘I can’t help it. I honestly wish I could.’ Marcel said, leaning his head back to stop the tears, which had begun to gather in his eyes, from escaping. ‘I feel like all the sand at the bottom of an hour glass or something. I feel like I’m coming undone – like I’m losing my fucking mind all the time! And, I don’t know, I just don’t want to feel like that anymore.’ ‘What do you want?’ The drag queen asked, running his hand over Marcel’s. ‘To get out of here.’ >> FAST FORWARD >> They kissed, turning over and over on their way back to Marcel’s apartment, heavily cross-faded and entwined in each other’s arms. Marcel liked the way that Zizi kissed him – so hard and vicious like he could have drawn blood. When at last they reached the apartment door Marcel looked around for his keys. The door creaked on its rusted hinges and paint fell in small fragments as he opened it. He had forgotten to close the window before leaving that morning. The apartment was cold and dark inside. In the summer, when the sun had been shining and there were great bursts of leaves on the trees, Marcel had woken up to a self he deemed worthless and climbed out of that window. He remembered sitting on the hard windowsill, his bare feet dangling over the pavement for what felt like forever but what was – in actuality – no more than a few soaring moments. He walked over and latched the window shut, but even shut he could still feel the window framing all the pain and despair and self-loathing he had built up inside. He had first realised he was depressed when he was thirteen. His parents had divorced and it seemed as though every single shred of joy and irreverence from his youth had been tarnished or devoured completely but the cold austere reality of living with his mental illness. He had spent most of his adolescence in psychiatric wards, staring day after day at the same white walls, finding it difficult to make friends or form lasting relationships. And when he realised that he was attracted to men he thought, fuck - another reason to hate myself. Zizi pressed slowly up behind him. His fingers dug in just under Marcel’s ribs and the honey of his breath fell fast against the back of his neck. Marcel turned around – his heart beating fast -– and they kissed again – as fervently as before. He couldn’t quite explain it but while he was being held in this stranger’s arms it was as though his insecurities simply melted away. For a few moments, he wasn’t ruminating on his own neurosis or crippling self-doubt. He wasn't caught up in the kind of masochistic thinking that had led him tumbling down the proverbial rabbit hole of antidepressants and half-hearted suicide attempts. The intensity of each brush of their lips demanded that he was mentally present, unencumbered by all the brutally bleak shit going on inside his head. Zizi moved his hands slowly down Marcel’s body and slid his shirt off his shoulders. Marcel smiled, picking the man up in his arms and carrying him through into the bedroom, holding him like la pieta. As he laid Zizi down, his spine relaxed and his feet arched into the cottony nest of the bed. Marcel climbed on top of him, his eyes gently expectant as they continued to undress, throwing their clothes wherever. >> FAST FORWARD >> Marcel woke the next morning to a small indentation in the bedding and the lingering smell of women’s perfume. He sat upright and sighed. The morning light, which shone through the curtains, cast his shadow across the bedroom floor and as he sat there, still half asleep, he found himself wondering whether his own shadow thought he was worth following. He yawned – his arms subconsciously reaching out for someone who was no longer there. Sometimes, he wasn’t so sure. << REWIND << The drag queen moved with a particular equanimity, swinging the covers off his body and standing up with ballet posture. He tip-toed around the room, picking his clothes off the floor – trying not to make a sound – as if the bedroom were a china shop, and he a bull. Impatient to leave, he unravelled his little black dress with the cut out décolleté at the back and ran his arms through the fabric, feeling the sensation of each thread and fibre as they lightly cascaded over his skin. He was doing what he had always done when he woke up in a stranger’s bed – panicking and running away – giving in to the little voice at the back of his head. From an early an age as he could remember he had thought that running from his feelings somehow made him free. He was still far too young to realise that it was the very things he chose to run from that defined him in the end. He leant down, gathered up his heels, and finished dressing. He looked different in the daylight without all his female affectations; without his make-up or his long hair brushed neat or his genitals tucked between his legs so that when he was performing he could convincingly pass for a woman. A lot of people didn’t really get drag. And that was okay. Not everyone had to understand why it was that he put on lipstick. In a culture that told certain people they were less valuable than others, the simplicity of existing proudly and beautifully was itself a kind of resistance. And when you came right down to it, maybe that was enough. He turned, giving one last look to Marcel before he left out the door. He was sleeping quietly on the bed. His face looked peaceful, lying there softly between the sheets. >> FAST FORWARD >> Marcel walked into the small independent record shop where he worked. A guitar riff recorded on old reel tape was playing over the speakers. He thought the shop was empty at first, but then he saw Saoirse sitting in the corner of the room. She was resting with her legs crossed on one of the old burlap sofas, tuning an original 1964 red Airline in her lap, her hand strumming the strings. ‘Morning.’ He said. Saoirse looked up from what she was doing. Marcel was smiling at her but she knew – almost intuitively – that he wasn’t alright. She didn’t know exactly what was up with him – just that his smile had an immediately perceptible air of sadness. ‘What’s wrong?’ She found herself asking. ‘Nothing.’ He shifted slightly, shaking his head. ‘Really, I’m fine.’ Saoirse put the vintage instrument down then, without saying a word, she stood up, walked over to the door, and switched the sign from reading open to reading closed. ‘You say that but then you look so far away. I was just thinkin’, sometimes, even when you’re smilin’, you look so sad – like you’re not okay, emotionally, on the inside I mean.’ Marcel fell down on the sofa. Saoirse came and sat next to him. ‘You really want to know?’ ‘Yes.’ She said in a softer tone, pulling herself closer to him. ‘It’s so screwed up. I mean, I should be happy,’ he said, feeling totally inadequate, ‘but there are some days I’m so sad that I don’t remember what it’s like not to be.’ He buried his face in her chest and began to cry. ‘I must seem pretty pathetic right about now.’ ‘It kills me when you talk that way about yourself.’ She hauled his legs up onto her lap and wrapped him up in her arms, holding him in a hug that was so passionately felt she hoped it would make him know that he was wanted. He couldn’t remember the last time someone had hugged him. It felt nice – just to be held. ‘I should be the one taking care of you, not the other way around. I’m young and I really do have so much to be thankful for–’ ‘–and that only makes you feel even worse because you think you have no right to be sad. I know that feeling.’ She said, her breath slow and shallow. ‘Sometimes, these things, they’re hard to see, but a hell of a lot harder to talk about.’ II PAUSE  Camara Fairweather (b. 1998) is a biracial writer, illustrator, and poet from the United Kingdom. He has worked for BBC Three and flagship programs such as Newsnight. He is currently studying at the University of East Anglia. Comments are closed.

|

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

April 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed