|

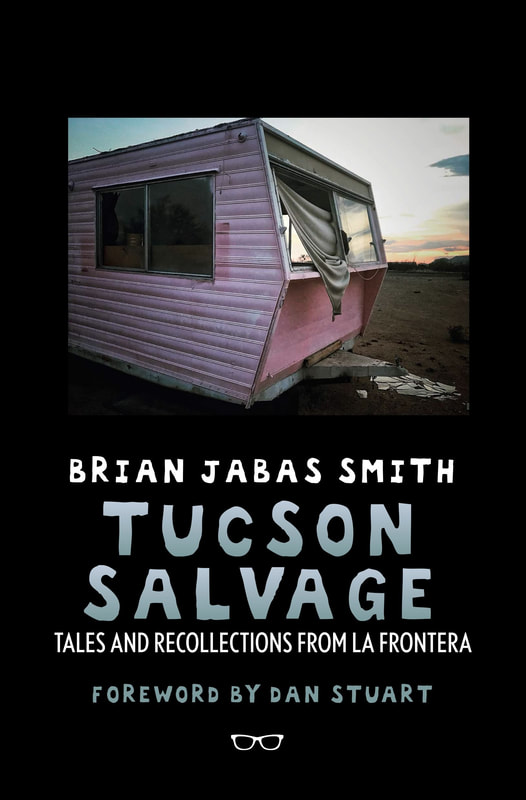

Brian Jabas Smith's Tucson Salvage How does one even begin to witness another person’s life? We see others inevitably through the prism of ourselves, all of our experiences, our fuck ups, wrong turns, heart aches, joys, fears and stumbling through the dark, hand searching for a wall that often isn’t there when we need most to lean into something that can hold all of our weight, that can sustain us. To understand suffering, one must. And survival, anyone living can speak to that, but the height of the climb and the fall has a hell of a lot to do with circumstance beyond one’s control, geography, neighborhood, the care one got or failed to get right out of the gate. Some go out into the desert with a pack full of new gear, others don’t even have the shoes for the journey. Brian Jabas Smith is a compassionate observer of the human condition. Sometimes his compassion surprises him. People aren’t what he expected, like the bartender of the Chatterbox, Isabel’s boyfriend, David, who bares his piece of soul at an unexpected moment; “He talks of touching people’s lives, through art (tattooing), through animals (his ranch) through kindness (“It’s about helping people get to the next place”). You hate yourself because you are surprised.” We make snap judgements out of survival instinct, we’d be dead if we didn’t size up what is before us pretty quickly. But Smith has an acute sense of smell for the goodness inside us all. It surprises those of us most who’ve fallen by the wayside a few too many times before. Every crash creates a thicker skin, or a softer heart, often both. The rest of our lives is a negotiation with our harder and softer selves. Isabel’s previous boyfriend broke her spine and left her for hours lying in agony on the floor. David is tough and hard to read at first, but as Smith soon detects he is just worried about the love of his life, like anyone would be, working in such a dangerous bar. In this place at the end of the world where “You know of the lady who was living in her car with her Chihuahua…She’d come into The Chatterbox and plug in her rice cooker and drink free soda until one day she was gone. Just like that.” You want to believe she’s okay now, wherever it is her car has taken her, the next town ahead. You don’t want to believe the worst even if experience has taught you that the worst is most often how it ends for far too many of us driving on hard luck roads with hard luck lives. This bar has been standing since World War 2, its barstools carrying the weight of “unemployed machinists and broken newlyweds and alcoholic liars and the hit-upons and best friends and anyone you can personally name who’d manned a stool here.” If these walls could talk they would wail and wail and wail. Isabel could easily be cynical and resigned to the ugliness of the human condition, but “there’s no jaded air of drink-slinger responsibility about her; you understand how she’s comfortable in her skin in that way people are who’ve not let life punishments erode trust and curiosity in others.” The same could be said of the narrator of these small, broken and beautiful lives as well. Brian Jabas Smith has lived the long nights and upended days, and he has arrived here with a compassionate heart still intact. And curiosity. What lies beneath the gruff exterior, where is the humanity we might, at any moment, be missing out on in the other? How do we look for that? How do we pay enough attention without caricaturing what we find before us? “Still you marvel how Isabel is not lost to chaos. Because you are, still. She has her code and so does David. You walk out of there. You tally the ways how the two people are nothing like you, and you suddenly care about them so much it surprises you. At the Chatterbox on a lonely Monday night in June in Tucson.” Tuscon Salvage is filled with the heartbreaking stories of real people living hard lives in the most unforgiving of landscapes. A place where “Alcoholic ghosts with suffering faces – ruddy with busted capillaries – circulate the dirty corners and bus stops.” “I could’ve been, or maybe should be, one of them,” Smith observes in the opening chapter, which serves as a compass of his own life history, he’s felt it too, this desperation and sadness. He observes in the hookers on Alvernon how “their entire beings wilt or rage in direct proportion to the level of meth or catastrophe in their systems, but in the watery streetlight, they’re nearly translucent.” He remembers in that moment “the young mother who lived next door years ago, the last time I’d lived in Tucson. How she committed suicide at the now-abandoned filling station at Pima and Alvernon. How she pumped gasoline over herself and sparked a lighter. How she left behind two little daughters. How before she died, I’d read to her girls out in the sun in my front yard, and they’d stare back at me with eyes all big and curious, faces candy-sticky. Sometimes the littler one would climb onto my back and yank pieces of my hair.” Which brings on the painful memory of a close friend’s suicide “my brilliant running bud Doug Hopkins and how he’d stay with us in our casita over on Camilla Street. He’d blow in from Phoenix, sometimes on a freight train, and we’d kill nights in Tucson, and in Nogales, like we did when we lived in Phoenix. I wanted to die too when he committed suicide. His big-footed, see-beauty-in-everything drunken self still stumbles all over this low, dusty town. His sweet pop songs are on the radio, still.” Every city has got a soul. And the people in it, more lost than found, struggling for light that is so damn hard to find. Every one has a story, that’s true enough, and while most here are tragedies the light at the end of the tunnel isn’t always an oncoming train. Sometimes it’s just the other side. We walk clear into an almost blinding light and we don’t how we made it through, but we did, those of us still living. The ghost of Smith’s mother (who wasn’t ready to go) and his father (who died of cancer), they are everywhere, losses that don’t add up, that leave God sized holes in him so hard to mend. We pick up the trail of where we come from and where we’re going and try not to let what we’ve lost here make us dark inside. His father’s presence still presses near sweetly; “I’ll hear his tenor sax ostinatos and gentle guitar runs, like he’s next to me playing with a passion only he could get lost in.” A phantom song in the air that reminds one that those we lose have a way of staying with us no matter where it is they’ve gone next. We can find them in the hills, the breeze off the lake, a child’s laughter, and in darker moments too, we carry them with us like lodestars. Observation is lifeless if not informed by life. The taste of it, bitter and sweet. One doesn’t work without the other. Smith has a way of looking under the hood of rough exteriors and finding what’s wrong with the engine, so to speak. In the Bravo base where vet’s organize an encampment, a home for the homeless. A place where, beyond the right wing pull of the orbit, Smith can see that something good is being done here despite the ugliness that might come with it. Walking amidst “beards tinted yellow from years of nicotine. Squint and they could be unclaimed bodies arranged neatly in morgues, lost to a frigid society. They’re not. They’re saved.” One broken brother in arms helping another. “One vet couldn’t live in four walls, ever, not after Nam. Veterans On Patrol built him a little house – volunteer high school kids from PPEP YouthBuild Tucson did the heavy lifting – that sits in the center of camp, christened Mercy Huss House. The little wooden abode is symbolic too. An on-site show of putting homeless in homes. Here he’s surrounded by Army tents and dirt and squalor and death and drugs and booze problems, and the train, which rumbles by morning and nights, loud as thunder. He’s happy. Beats the underpass in monsoons.” Don’t need much to be happy when on-the-outs is where one has spent most of their lives. You become grateful for the small things. Out here, they are not so small. Walking the halls with Fred, Smith writes; “His silence commands in that way that makes him easy to respect. Like anyone who’s been off to battle, in the gory war fields, in the years of feral homelessness, with the bottle, with the speed. [His roommate and] others call him the camp patriarch. Says Fred experienced things in Nam that no human should ever have to. Ever. Says Fred got blown up too. I imagine, above all else, in this minute, that Fred is uncomfortable with any moments of tenderness. The terrifying insides of his mind.” To accompany a man on such a short walk and yet be able to feel the fire inside him, the heavy load on his back. Empathy is a practice. It’s not like breathing, you have to count down deep inside yourself for the next intake and exhalation. You have to pay close attention to something that happens so quickly in someone else, if you blinked, you’d miss it. Who and how they are. Another Vet “He’s a cancer survivor – a ruptured tumor in his head nearly killed him. (“People ask why I’m so happy. Well, I’ve already seen death twice.”) Some of us count our blessings from scratch. Don’t need much, four walls, a warm meal, a few people around us who’ve seen and survived the same shit. Who’ve been to hell and never came back, not the same. “Resignation to an existence with others whose only commonalities are military or homelessness or both. Sometimes that isn’t much. But it makes Bravo, as homeless vet G. Cross tells me, a family. Evenings are often spent around a fire, people conversing, old school.” “Cross is kind, admittedly lost, pretty soft-spoken. I get the feeling he never mattered enough to anyone to be a focus of concern. He says, “How are you gonna get started if you have no one and no home? People don’t hire people who are 58-and-a-half. What are my skills? I can drive. I can speak Farsi, Spanish.” He’s hanging on until November, when his military bene- fits kick in. Until then he’s got nada. Says he’d moved from his Arizona home to Sonora because it was cheaper to live. Says lots of vets do that now. It’s becoming a thing. Vets can’t find work stateside so they go to Mexico. It’s that or homelessness. He leads to Bravo’s outdoor “field shower.” He’d just re- paired it, easier flow for the water bag mounted above, and he’d made it more usable, extra room, added some waterproof flooring he’d found. He’s proud of it. He talks about creating a garden in back, using shower gray water.” Repairing the water in the line, growing a garden, these small things are not so small, not in this place. Cross, in this sacred and broken moment, matters enough to Smith to be a focus of concern and care. Underneath the hood, that engine is so much stronger than its breakdown. Smith has come through his own version of many of the troubles that beset the beautifully broken and resilient people in this book. But suffering has not made him hard or indifferent, it has made him curious as to how other's do what is most impossible to do when a life is run aground for so long; come through with an intact soul and a beating, compassionate heart. When is a life not salvageable? When is it too late? Is it ever, really, too late? These vessels are but bodies lost in the desert, in a wandering so deep the pain is the air you breathe. To be a torch in such darkness is to know that if you yourself somehow came ashore, others can too. It's to listen with your nerves. In Tuscon Salvage, it is lives, unseen and unspoken that are salvaged. Pains collected, front cover to back, witnessed by a man who has seen the dark and reached for the light. He has lost things, like others in this desert. Is still here, impossibly alive, and curious enough. And surprised by what he finds. The beauty and the breakdown. If these walls could talk they would break your heart. Preorders available now from Eyewear. Visit www.briansmithwriter.com/ for more. Comments are closed.

|

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

April 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed