|

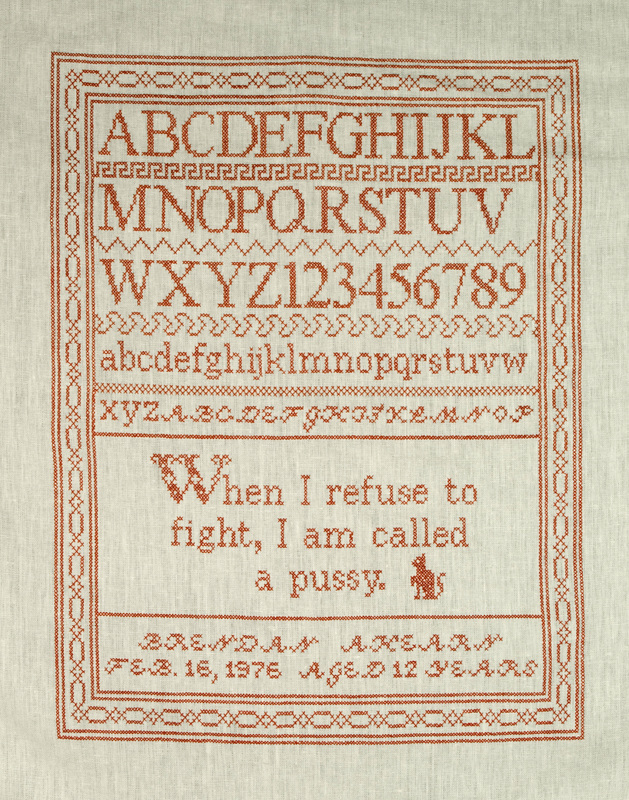

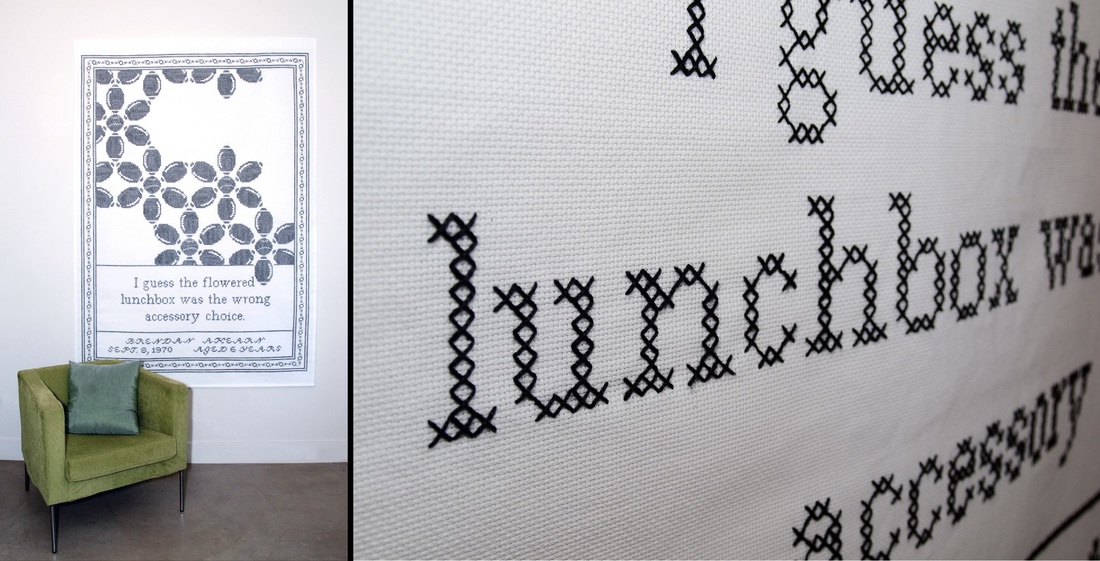

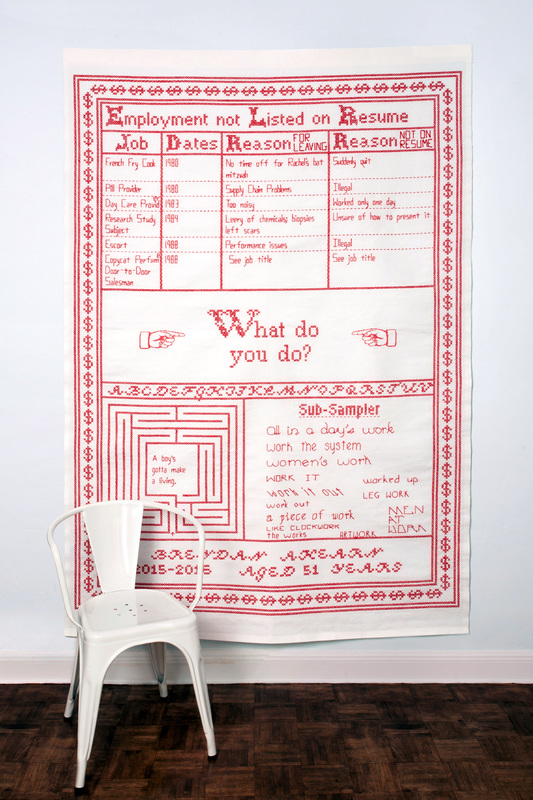

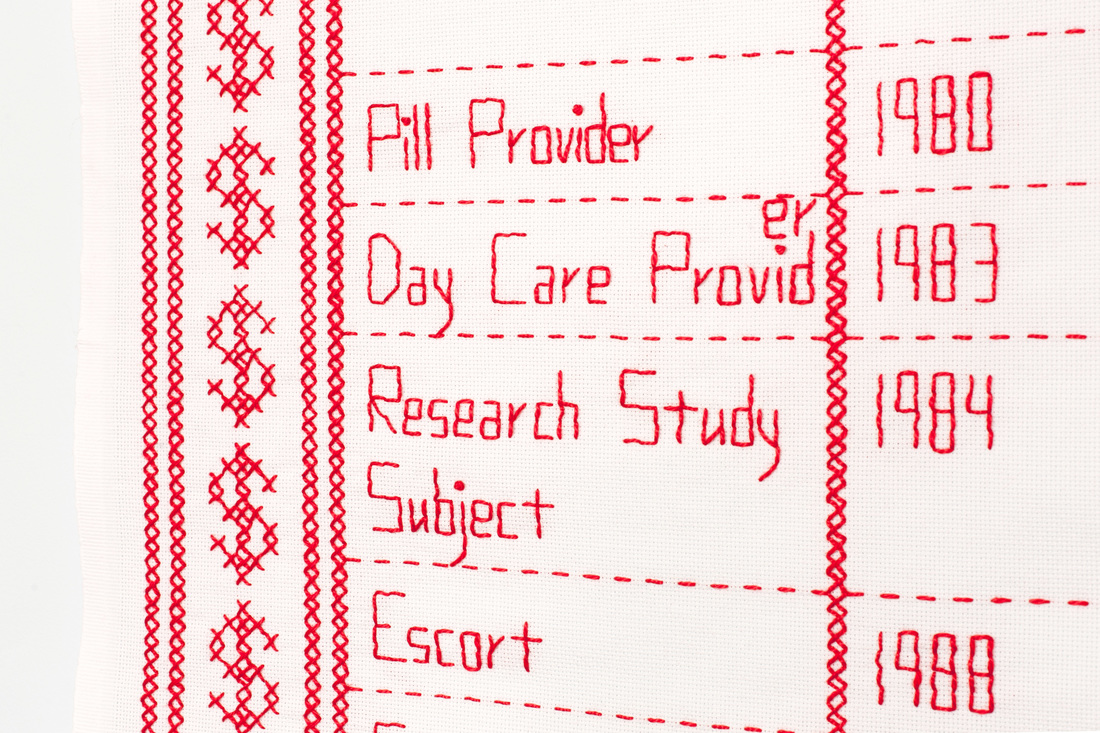

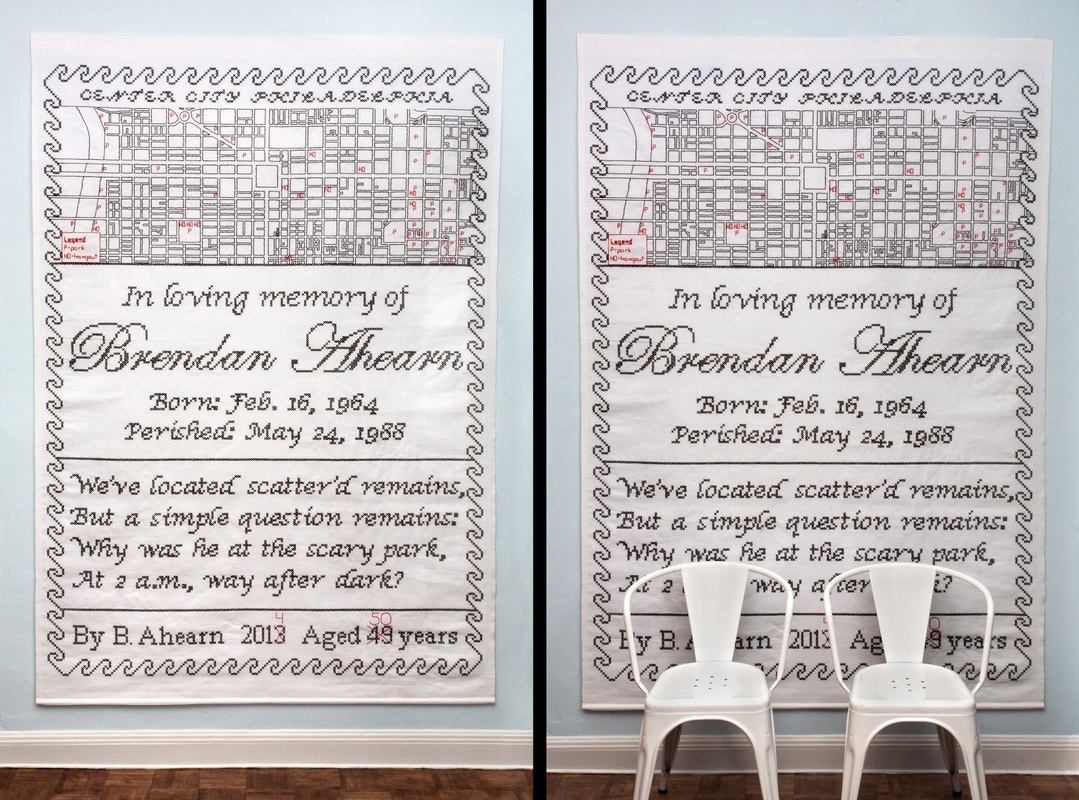

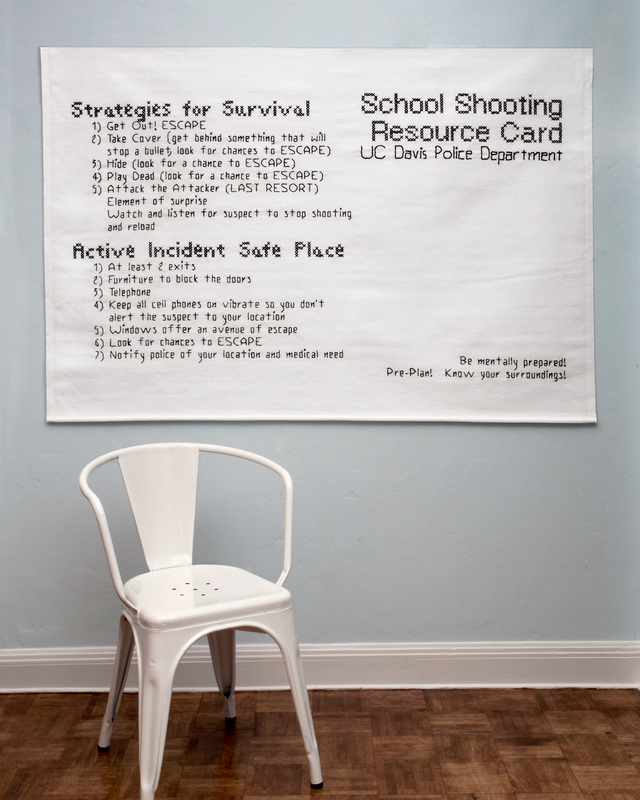

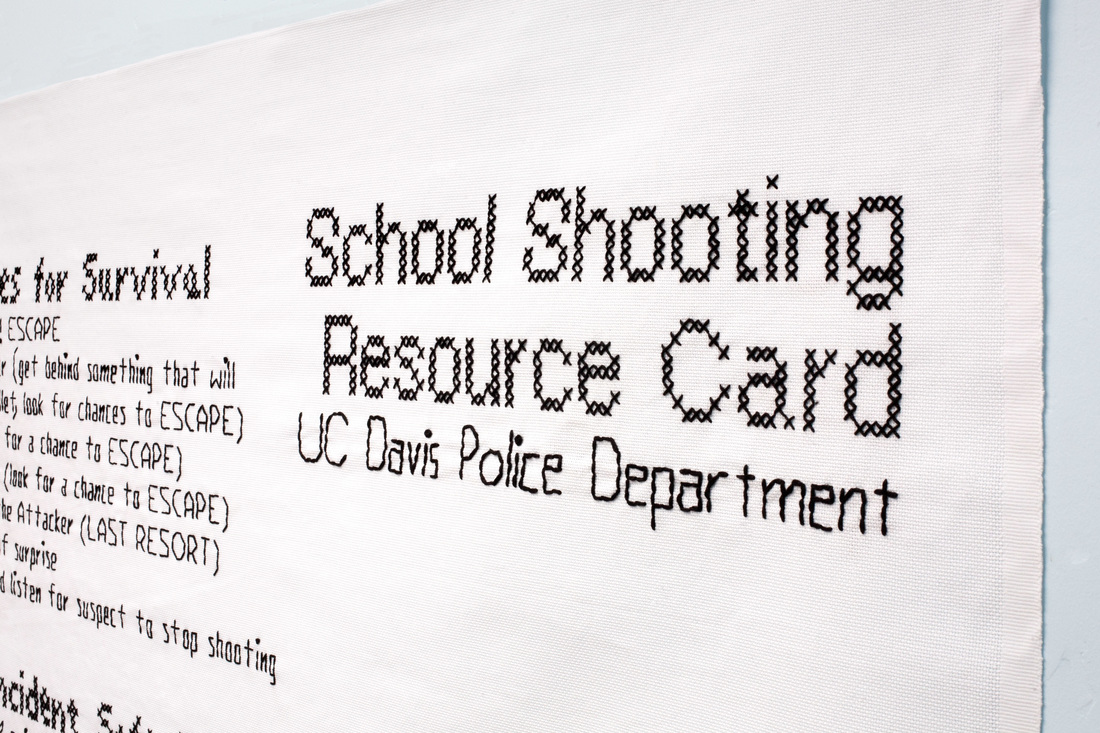

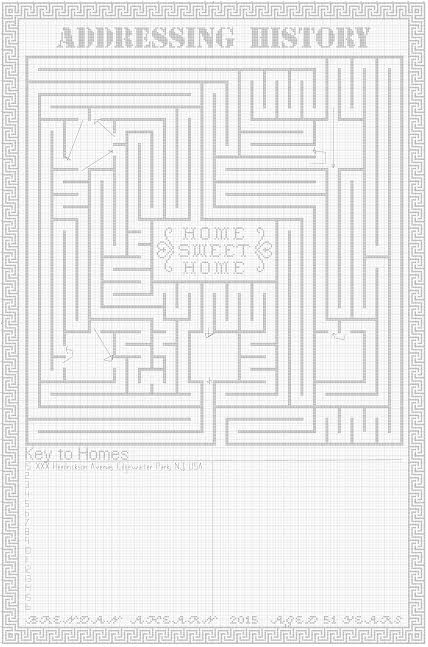

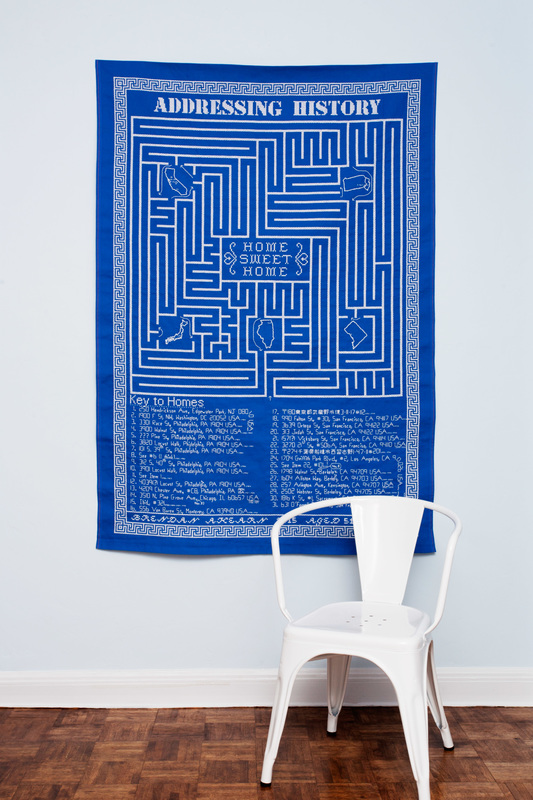

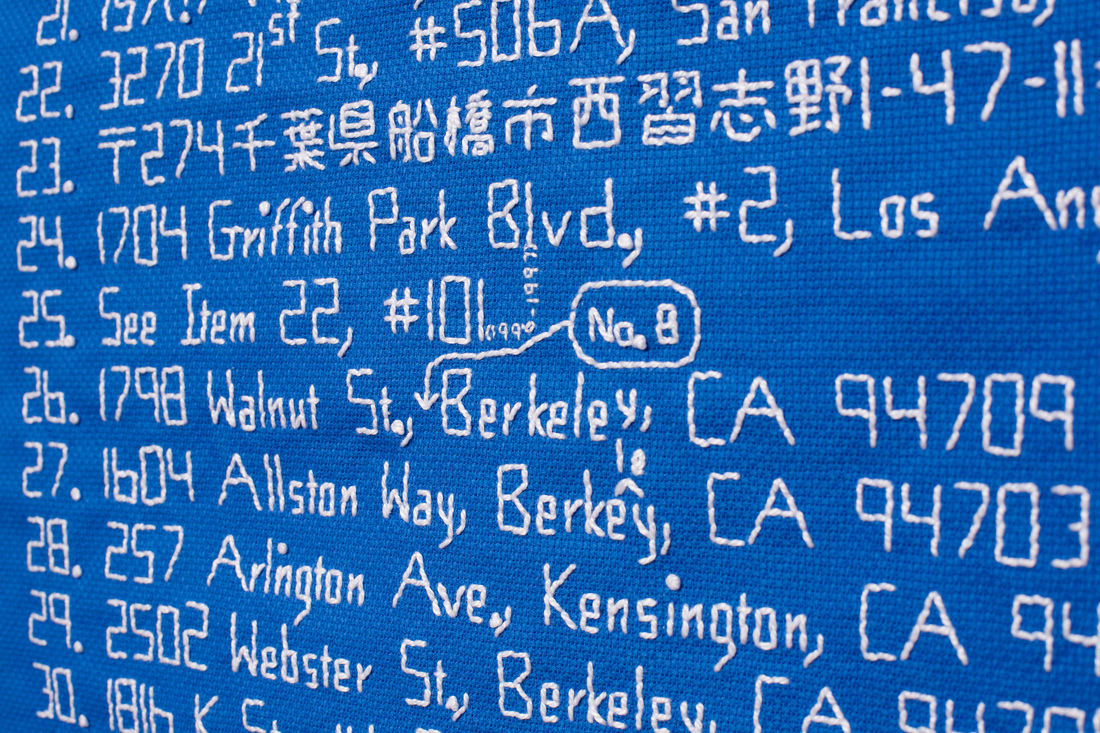

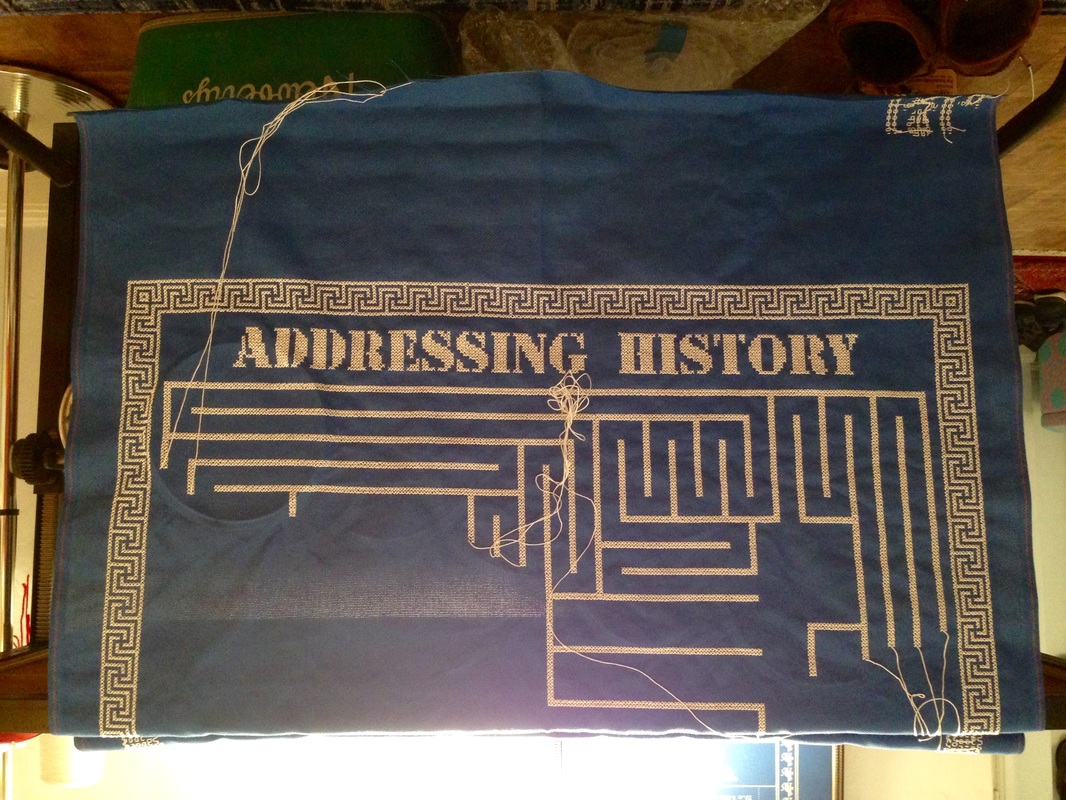

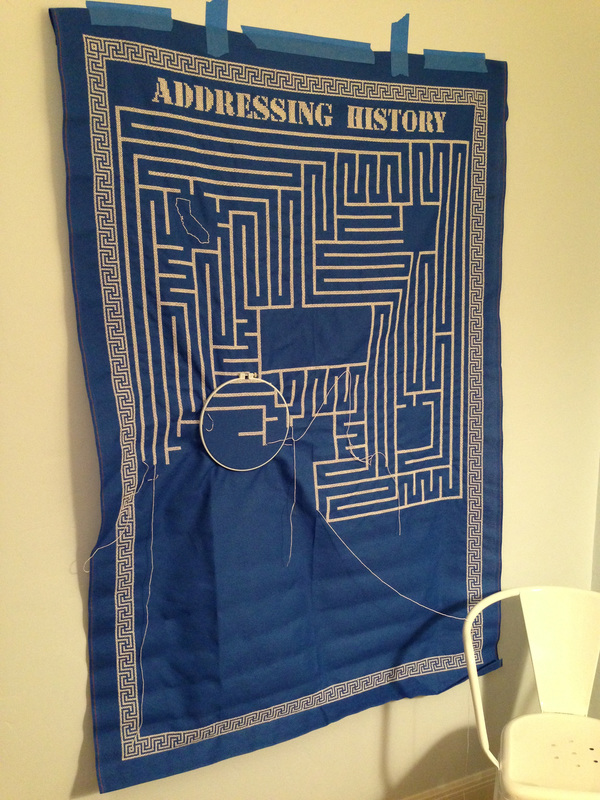

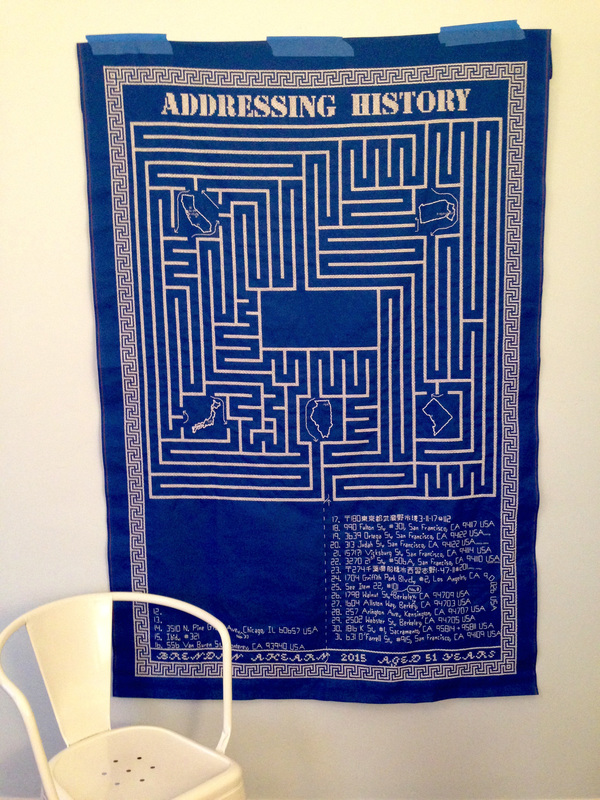

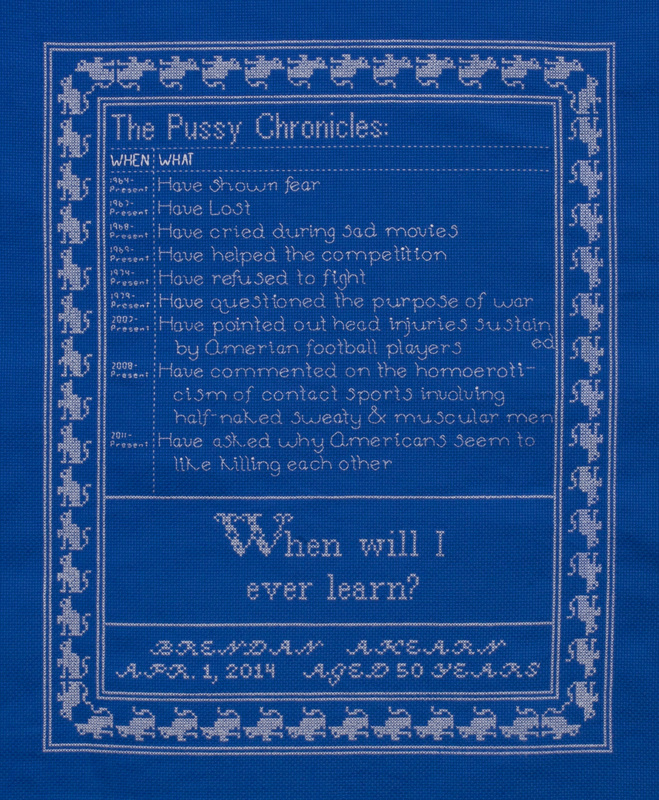

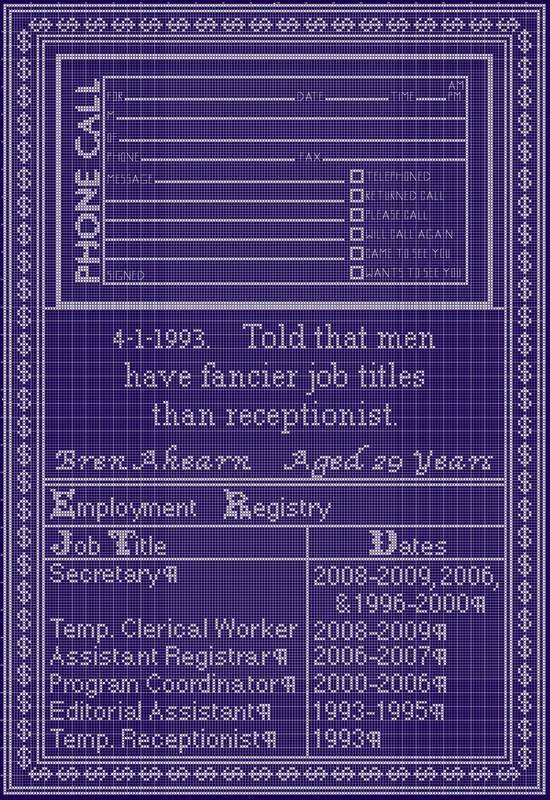

8/19/2016 Interview with Artist Bren AhearnAHC: Can you tell us a bit about your process, themes & inspirations? Bren: One main inspiration is the socialization of American men to be violent and my attempts to navigate this socialization. This violence can be physical, verbal or spatial. An example of spatial violence is the taking up more than one’s fair share of space, such as “manspreading.” Here’s an article about manspreading in the New York Times: www.nytimes.com/2014/12/21/nyregion/MTA-targets-manspreading-on-new-york-city-subways.html My feeling at odds with this socialization is a key theme in my work, and I use the cross stitch sampler form to reflect back on my life and how I’ve been educated to be a man. Historically samplers were used as part of the education and training of girls to be proper women, so the sampler form fits in with my reflections on my education. Sampler #1: linen, cotton; 19.75"H X 15.5"W (Framed: 25"H X 20.5"W); 2008; Photo: Allison Tungseth Sampler #9 recounts my first day of first grade, when I showed up at school with a lime green floral lunchbox. I quickly learned that boys should not have flowered lunch boxes. To my parents’ credit, they allowed me to select the non-traditional box. Sampler #9: cotton; 88"H X 60"W; 2011; Photo: Kiny McCarrick I currently have an exhibit at the Bellevue Arts Museum, entitled Strategies for Survival www.bellevuearts.org/exhibitions/bren_ahearn.html in which a few of my samplers and active shooter pieces are featured. The curator, Stefano Catalani, is an eloquent spokesperson for my work and notes the following about my samplers: “Bren Ahearn reclaims this craft to transform each of his samplers into a page from a personal and intimate diary filled with the awkward moments, defeats, and discoveries which are the result of dealing with our culture's gendered expectations.” In addition to gender, there are some other themes, such as my work history, in my samplers. For example, I have samplers exploring my gendered feminine work experience (e.g., secretary, receptionist) and how I’ve wasted time at work. I explained a bit about these two samplers in a recent interview with Dan Crowder on textileartist.org www.textileartist.org/bren-ahearn-spin-me-a-tale/ so perhaps readers who are interested in more info about those samplers could take a peek there. My most recent sampler explores jobs, legal and illegal, that do not appear on my resume. Sampler #18: cotton; 88"H X 60"W; 2016; Photo: Miles Mattison Additionally, I’ve been exploring death with my death samplers. These samplers are based on times in my youth when I may not have exhibited the soundest judgment, but I was lucky and am still alive. In the samplers, however, I recall a parallel history and was killed or died. This series was inspired by nasty, judgmental comments that people leave at the end of tragic online news stories. It makes me sad that some people blame the victim. Sampler #12: cotton; 88"H X 60"W; 2014; Photo: Miles Mattison Another main recent influence is the active shooter situation in the United States. To me it’s crazy that the situation is so normalized that there’s even a name for the situation: an active shooter situation. When I worked at the University of California, Davis, we were called into the auditorium and trained on how to stay alive if an active shooter arrives. We were given a handy card at the end, and I stitched a larger version: Active Shooter Directions #1: cotton; 42"H X 60"W; 2011; Photo: Miles Mattison Recently I’ve been creating stripped down versions of the three main things the US Department of Homeland Security instructs on what to do in these situations. I’ve been making these in different fonts, and they’re my next generation sampler, since they’re part of my educational process. I’ve made about eight of these so far. Active Shooter Directions #3, 4, 5: cotton; 39"H X 59.5"W (each); 2016; Photo: Miles Mattison Finally, life in general is a big influence. An artist friend told me a while back that his gallerist (or someone in a career-dealing capacity) told him that he shouldn’t have another job other than artist (or announce the fact that he has another job). I guess this was so my friend would appear to be a “real artist.” For me, I’m grateful for the non-artist jobs I’ve had, as they’ve given me rich content for my work (e.g., active shooters and jobs not on my CV). They’re part of my story. I feel that this censoring of my artist friend’s other jobs minimizes the fact that in the US it’s difficult to make a living as a fine artist, and many artists by necessity have other jobs or patrons or sugar daddies. (As a side note: My husband’s name is Doug, so when I was in school, I called him my sugar Dougie.) In terms of process: This is a rough sketch of what I do: a. An idea comes into my head. b. I write down the idea in my notebook. c. I think a bit about the idea; I get inspired to create or I sit on the idea. d. If I get inspired to create a sampler, I start designing the sampler in Stitches for Mac, a cross stitch program. Sampler 16 Chart Sampler #16: cotton; 60"H X 40"W (approx.); 2015; Photo: Miles Mattison You’ll notice that on the above chart, not all of the addresses are filled in. Sometimes I don’t fully design the piece because it’s tedious. This often leads to mistakes, which I like, and are more in keeping with traditional samplers. e. I typically use 14-count AIDA cloth (which is cloth woven with 14 holes/inch in the vertical warp direction and 14 holes/inch in the horizontal weft direction, thus resulting in a grid I can use as a guide) that is starched, so I don’t need an embroidery hoop. One thing I do, though, is to start from the outside edges and then work my way in because the more I handle the cloth, the more the starch wears away, and the fabric becomes soft. Here are 3 in-progress shots of Sampler 16. In the third shot, you can see how I’m working from the bottom up in the left-hand address column. Please look beyond my sub-optimal photography. AHC: What first drew you to art? Was there a specific moment in your life or turning point where it became clear to you that you were being called to create? Bren: In that textileartist.org www.textileartist.org/bren-ahearn-spin-me-a-tale/ interview, I described a bit about my upbringing and creative family. I won’t repeat that text in case there are overlapping readers. One thing I’ll add to that narrative is that as I have become more confident in my skin, I’ve incorporated more of myself in my artwork. A key moment of this self-incorporation came when I was in school. A visiting professor assigned the class memorial projects in encaustic. I decided to do a memorial to my coming of age during the 1980s, when AIDS was at its height. There was a lot of fear, name-calling, etc., and I didn't quite know how to navigate life. When I presented the project to the class, I started crying. My class was very sympathetic; they said they understood that I was mourning a lost coming-of-age. Later, in private, the professor told me that I should not create "gay art," but I instead should just make "art." I am so grateful to her, as this galvanized my direction. Prior to this point, I was floundering about what to do. I saw that my life experiences had made her very uncomfortable. I then knew that this was good and that I should pursue the telling of my microhistory (which is the history of the individual common person, rather than history with a capital H). So, for my next project for the class, I passive-aggressively sewed pink lamé to the inside of an army tent and sewed on images of stereotypically gay things. Here is a photo of the model of the tent, which I actually like better than the full-sized final tent. Sewn on the outside is a photo of Aiden Shaw, who was a British gay porn star in the 1990s. Tent #1 Model: mixed media; 5"H X 7"W X 13.5"D; 2008; Photo: Allison Tungseth My presentation of my story has gotten a bit more subtle since this tent. The piece was a fun dalliance, though. The only thing that would have made it more fun would have been to have had the real Aiden Shaw in the tent. One thing I learned from this experience is that people either tend to love or hate my art. I would rather have it be this way than to have someone just be neutral about my art. AHC: Who are some of your influences? Bren: In that interview at textileartist.org www.textileartist.org/bren-ahearn-spin-me-a-tale/, I listed a few influential folks over there. Of course, I forgot a bunch of folks in that interview. So, I think I’ll just quit while I’m behind. I would, however, like to give credit to the folks in the San Francisco Loom and Shuttle weaving guild. I started my adult textile life as a weaver, and the people in this guild encouraged me to push myself and to try new things. They provided me the foundation to explore. Thanks to them all! AHC: In your work you deal with the conflicting messages of masculine expectations, deconstructing what lies behind the term "manhood" and exploring sensitivity in a cultural landscape which tends to devalue this quality in men, could you talk more about your own personal and artistic negotiation with these things? And also about the important role embroidery has played as a means of confronting these issues? Bren: Back in June 2016 I gave a gallery talk at the Bellevue Arts Museum and talked about this notion that American men are socialized to be tough and to have their emotions in control. One of the attendees noted that it is different now than when I grew up. I acknowledged that this is true; however, I often come across examples that make me wonder if this assertion is really true. For example, after I presented on a panel at a conference in 2010, a woman came up to me and said she would like to introduce her grandson to my artwork. She thought that her grandson might be gay and that her grandson's parents were not accepting of him. She thought that my artwork might encourage him to see that there are others like him. It was then that I realized that I can make a difference in people's lives with my artwork, and this inspired me to go on. This also reminded me of feelings of isolation in my youth. I wonder, though, if most people feel isolated and awkward in youth. In another example, in June 2016 I attended a banquet at which a man received a very prestigious award. He was very moved and was crying when he received his award. Later, a woman recounted the incident and she had a smile on her face when she relayed the fact that the recipient was crying. I don’t know if her smile meant that she was mocking him or that she felt uncomfortable or that she felt compassion for him or something else. To me, the smile seemed as though something was amiss. In the moment, though, I said nothing about her reaction. What caused me to say nothing? Was it fear of being an outcast? Was I not wanting to make waves? Was it so she could save face? Whatever the reason is, I regret not yet having said anything. I’ve been meaning to ask her what she was thinking. One of my friends has pointed out to me that it’s OK to go back and revisit an uncomfortable topic with someone for closure. In another example, I was on a light rail train in New Jersey, USA about 5 years ago, and a man was on the train with an infant boy. He was play-slapping the baby and telling the baby to hit him back and be a man. The baby was giggling at the play, but something didn’t sit right with me. It seemed at though the man wasn’t fully playing and was socializing the boy from infancy to assert his masculinity. I didn’t say anything because I was concerned the man might have a gun and kill me. As a means of confronting these issues -- embroidery, which currently is gendered feminine in the USA, in conjunction with the feminine history of the sampler form, allows me to invoke stereotypes in order to question stereotypes. (That’s a highfalutin sentence, isn’t it?) Sampler #13: cotton; Framed: 25.25"H X 20.75"W; 2014; Photo: Miles Mattison AHC: Do you have any upcoming exhibits or new projects you'd like to tell people about? In terms of new projects, I see exploring some 3-D projects, but maybe not until Doug and I move into a new space. Our current space is 480 square feet (44.5 square meters), which inspires me to continue making flat pieces or things that can be rolled up. Bren: I would like to continue with the stripped-down active shooter directions pieces in different fonts. I could see a whole room full of them. I also would like to revisit some of my blueprints. A few years ago I had a show in a space with a lot of skinny, irregular wall areas. I didn’t have enough framed small samplers for the small areas, so I printed off some of my charts with white Xs and a blue background, in order to evoke blueprints, another antiquated form. Sampler 5 Chart: digital print, variable dimensions, 2013

About shows: As mentioned above, I have the Bren Ahearn: Strategies for Survival show at the Bellevue Arts Museum in Bellevue, WA, USA until mid-January 2017. www.bellevuearts.org/exhibitions/bren_ahearn.html Here is a link to a review of the Bellevue show: www.seattletimes.com/entertainment/visual-arts/artist-confronts-gun-violence-gender-roles-through-embroidery/ I might have a few pieces in the show at the annual Mid-Atlantic LGBTQA Conference at Bloomsburg University in Bloomsburg, PA, USA if I can get my act together and do the submission, and if I get accepted. I will have a piece or two in the Loom and Shuttle show, Woven Together: Experience and Expression, at the Sanchez Art Center, Pacifica, CA, USA, January 13-February 12, 2017. I will have a few pieces in the Social Fabric/Moral Fiber exhibit at Gallery West, Grant Campus of Suffolk County Community College, Brentwood, NY, USA, February 14-March 30, 2017. The curators are Leila Daw and Michaelann Tostanoski, and I will post info on my website. Here is my website, where I’ll post info: brenahearn.com/ Thanks for this opportunity to chat about my work! Comments are closed.

|

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

April 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed