|

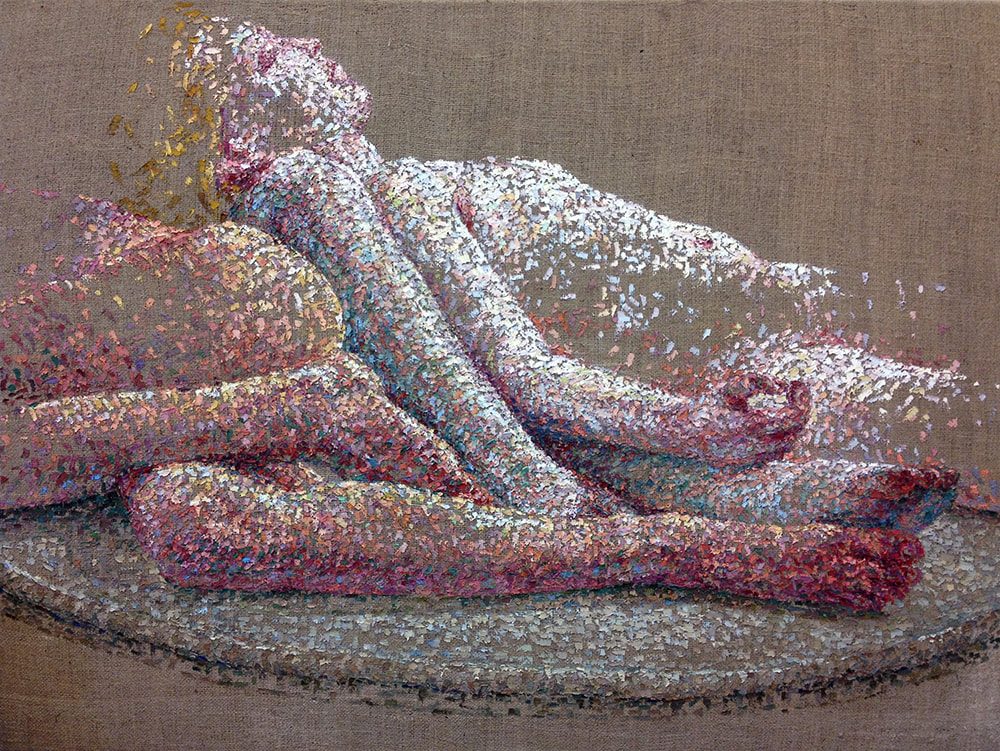

And Yet, I Feel Fine - 2013 - oil on burlap The art of Kiley Ames works against the grain, with burlap as her surface, she has chosen a medium that works against her because, as she puts it, "even though it is really rough and unforgiving you can still use it to create a variety of really unique and beautiful things. That's how I see people and that's how I see society." A unique and soulfully poetic psychology infuses Kiley's work, the difficulty of the medium stands as metaphor for the challenging surfaces and all too often interiors of people and of our world. The world beyond the familiar is also one that Kiley is deeply fascinated by, with every trip abroad, she says, "I start a different form of art, it just contributes to how I think about art, how I think about people and the relationship that we have with different cultures. Sometimes I find more commonality with different cultures than I do in this country." In China, Ames picked up her appreciation for negative space, which shows up in much of her work, and could also be seen as an offering to the viewer's own potential for dreaming up possibilities, both in what they see and what they don't, perhaps layering in their own miniature visions like an unspoken collaboration. Kiley's work is by no means an art of isolation, but rather one of connection and world responsiveness. What is the fabric that holds us together, do the ties that bind also sometimes discomfort us, how do we work against ourselves, each other, the world, otherness, what we see, what we don't? I spoke with Kiley recently about her work, her medium, the ways in which technology has transformed and compromised our ability to remember deeply our histories, the loss of art programs in public schools, what artists can do to remedy it, and ultimately the world at large, because more than anything, the art of Kiley Ames stands as testament to the fact that there is always much more than meets the eye, that what we know, can at any moment, be totally transformed by what we don't. James Diaz: What are your ideas behind working with material that works against you, such as burlap, why that material and how did it first come to you to use burlap as a canvas? Kiley Ames: When I had gone to graduate school I was painting on panel with brushes and I loved it. It was a really comfortable surface for me to work on, and even though I was getting really positive feedback when I was graduating I was really unhappy, not so much with the images that I was creating, but the disconnect between the content I was trying to create and how that was not being articulated in the actual image I was creating. I had just received a residency to go and study in China for a few months and I had an instructor who I could communicate really well with and he said "you need to choose a surface that works against you." Basically go opposite with everything I was using up until that point. So instead of painting on panel choose a surface that was really rough and really unforgiving, and that had different context to it, the actual burlap itself, and then I picked up a palette knife instead of a brush. Working with burlap still till this day is really challenging. I love how the burlap contradicts the imagery I create, because it's really rough, and multi-purposeful, it's recyclable, people throw it out, it can be also fabric that is used in these really beautiful creations, and even though it is really rough and unforgiving you can still use it to create a variety of really unique and beautiful things. That's how I see people and that's how I see society. Even after several years of working with burlap it has never become a comfortable surface for me. And I feel as if life has never been a comfortable existence for me. JD: I was thinking along those terms as well, how it might relate to how we see other people, the burlap working against you as opposed to the canvas, which is a little more passive and easy to deal with but the burlap forces you to grapple with something. KA: I think the wood panel had become a passive surface, which really works for some people and had been successful, in a way, for me, but that's not what I was looking for because that's really not what defines me and how I view people. JD: The titles of some of your works, Atonal Melodies, In the Labyrinth, I think of these in terms of people too, people being labyrinths, being melodies that are slightly off or aren't always on key, the discrepancy between who they are and how we perceive them, is that intentional at all behind the titles of your series? KA: Absolutely. The titles have become a huge part of the whole piece which definitely was not how it used to be. I'm hugely influenced by literature and so many of the titles come from different books I've read over the years, different words that I am always drawn to that recombine to create a title. It always comes at the end of the process and so in many ways it becomes the final part of the piece that I feel complete with. JD: Who are some of the authors that have inspired you and crossed over into your work? KA: It's such a huge range. I would say Virginia Wolfe. I was a history major so authors like James McPherson who wrote books about the civil war, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Tolstoy, Greek Mythology, which was also one of my favorite things to study, The Odyssey, it really crosses such huge fields, Edgar Allen Poe, Walt Whitman. Duality - 2017 - oil on canvas J.D. The study of literature and history came before you entered art? KA: Yes. I was a history and English literature minor at UCLA. Then went into Italian and started to study art history. It really wasn't until my mid-late twenties that I ended up taking a figurative oil painting class and that set me back to school again to get a degree in studio art. JD: Having studied abroad and having lived in a few other countries, how has that impacted or translated into your work, in terms of observing other cultures and languages and the different ways communities are around each other, has that made an impact on your own work. KA: Absolutely, I think that helps define my work. Which is why I go on as many residencies as I can. When I first went to China on the residency which resulted in me changing the surface of my technique, we also were really fortunate to have another student who acted as a translator and we spoke with a lot of Chinese artists and they talked about the history of how Chinese painting developed, which is so completely different from the way western art developed. A lot of the composition that I use now in my work, where there is a lot more relationship between the negative space and the texture of the burlap versus the painted areas, that was really due to my exposure to Eastern art, and how the canvas or the empty spaces were considered just as much if not more relevant to that whole image. When I was in Beijing we were put in the middle of the city and it was a fend for yourself situation, it was incredibly alienating. There were four of us and nobody spoke the language, we weren't in a tourist section, we didn't know how to order food, we didn't have access to social media, I think I got maybe a half hour of Skype with my family outside of a McDonald's, so it was really alienating. It was an incredible experience which totally changed the trajectory of my artwork but at the same time it was a very contradictory experience. This Beautiful Sound - 2017 - oil on linen JD: And hard to ground yourself in such an uncertain environment. KA: Definitely. And then later studying in Germany, with all of the cultural difference that entailed, I first began doing sculptures. Every different place that I go to I start a different form of art, it just contributes to how I think about art, how I think about people and the relationship that we have with different cultures. Sometimes I find more commonality with different cultures than I do in this country. I wish more people had that experience and didn't feel so committed to their own culture that it dis-inhibits them from allowing other cultures to have an influence and impact on them. JD: I wonder if any of that in this country could be attributed to speed and how fast our society is, how technology has changed, our attention span is shrinking and our appreciation of things is so miniaturized. I'm sure this is affecting other cultures as well but maybe it's not affecting them as fast or in the same way or maybe there are parts of their society that have managed to hold onto older forms, mythology and ancestral story telling and generational culture that is preserved in ways that it isn't here except maybe in Native American communities and the like. KA: I completely agree. I think that the U.S. is such a young culture, it has a young history to it and while there are obviously these really significant cultural shifts that have happened in the U.S. I think so many other cultures have a much more significant depth of history that they can go back to. This country does tend to speed things up so quickly, contradictorily though I kind of feel like we're going backward at the same time, which I think has thrown a lot of people off, myself included. JD: Politically or artistically? KA: I think socially we have gone back and maybe that's reflected in the current political climate. Progress moves in waves, you have huge jumps forward and then it plateaus, and apparently goes backward before it goes forward again. I'm more conscious of it in this country because that's where I live but I'm sure that also happens in other countries as well. JD: Do you attribute that to a loss of solidarity that people have with each other, how communities are in flux and rarely stable anymore? KA: In this country? JD: In any country but in this country too, to some degree. KA: I definitely think that we have sped up our attention to history. History books I used to read in school, or the emphasis that was placed on literature and science, I felt as if it was kind of abbreviated back then, but I feel now, especially with the way technology has progressed, that there's an even shorter attention span for history, and I'm of the belief that if you don't understand your history you don't know how to move forward. You either get stuck in the present or you get stuck with what you were taught in the past, and to me societies can't evolve unless you know what your past is. And what other people's histories are. Great Ladies at Work and Play #2 - 2012 - wire, paper clay, burlap, oil paint Sky with No Ceiling - 2017 - oil on linen JD: From a young age people are learning history not in a deep way but on the surface, and tests become increasingly geared toward memorization as opposed to really absorbing the information. KA: I think that's true. I don't think that's always intentional, depending on where you're raised, how you're raised, what your access is to certain things, those are factors that we definitely don't always choose. That plays into economics, that plays into demographics, where the emphasis of value is placed. I think in general there is a lack of emphasis on education and on learning what your past is and the complexities of that past. JD: Technology too is geared towards taking young people's attention away from the permanent and putting it onto the fleeting. I didn't grow up with that kind of technology in school, so maybe there was less competing for my attention, although there was still stuff competing for my attention other than school. But today it seems it would be even harder to instill a deep appreciation, whether in middle school, high school or even earlier in kids with that kind of bombardment of over-sensory stimulation towards really fleeting and artificial, temporary things. KA: I agree. If that's what's encouraged and there's only so much influence individuals can have over such large societal problems as that because they're encouraged on such a large scale, and I don't think it's going to work to societies benefit. I find technology fascinating, don't get me wrong. JD: I do too. There's a tendency to either denigrate it or over romanticize it and not many of us live in the in between of appreciating the benefits and the downside. KA: I feel as if it hurts the communication that people have with one another. I think communication can often be abbreviated now, whereas before you had two options, you could talk in person or you could talk on the phone. Or you could write letters. A lot of people are losing their communication skills which is how you often learn from one another. JD: Letter writing is a great example, it forces you to think about what you really want to say when you have a pen and paper and you're writing somebody. I know that when I've written letters personally it's always been an in depth process. Emails and instant messaging takes all that away, not that we don't still agonize over what we're going to type but it feels different. KA: I still write letters to friends over seas because you have to think more about what you're going to say and you can't really hit the delete button and I like that. Study for Appreciate the Other - 2014 - wire, air dry clay, oil paint The Light that Leads - 2013 - oil on burlap JD: Talking about education, so many art programs are being cut in school, what do you think the impact of that is for youth, not that every young person is going to become an artist but that they have that appreciation for art or art history removed from their curriculum, what affect does that have on young people and on our society, what can artists and even people who aren't artists do to turn that trend around? KA: I think it's absolutely horrible that the first thing they end up cutting are arts programs because I might not have taken all these studio art classes or majored in art but we always learned about it and there was always the option to take it. I Think in high school I took a jewelry making class, and you were still exposed to creativity, and I feel as if so many people, myself included, can relate to humanity or these range of emotions with various methods, some people relate to music better or some people relate to visual art or literature and if you cut out these visual art programs you're cutting out this huge section of kids and even young adults where that's their outlet and how they understand themselves and their relationship to society and to other people. And it limits your knowledge base, and your communication base. I think of what my life would be like now if I didn't have my art and I would find it so isolating. I think as artists or in any creative field, but especially in the arts because most people can turn on a radio, if students are not provided with that art then I think artists need to bring that into the community. That could be through grants provided for community or mural projects, or after school classes, where kids or young adults can go to these programs at minimal cost or free of charge because they're funded and get that experience. I think it needs to get there somehow. If you look back at civilization, images figure immensely in the social fabric. I can't think of a culture that didn't use visual art as communication. JD: When that gets stifled expression has nowhere to go. And then violence emerges. As a young person I had an appreciation for writing and I had teachers that encouraged and even instilled that, and the more that that is lost, whatever a person is dealing with in their own personal life just becomes magnified and has nowhere to go. And so if there's no appreciation for the visual, no appreciation for literature and that's lost, it's pretty scary to think of what we'd become or who we'd become. KA: I agree. I think a lot of artists feel that way. You get caught in the fact that you want to create and have time to devote to your own art, at the same time you want to make sure that other people can experience your art and be involved in that relationship and experience. And if you take that away, the lesser you're able to express yourself and the more you become internalized without having that outlet, I think people and society just implode. JD: How do you view the gallery space, do you think galleries could become more democratized and accessible than they are now? Does that play into artists setting up these programs like you were talking about, in communities, making up for maybe some of the structural barriers to people experiencing and seeing art? KA: I think the gallery system has changed so dramatically from what it was in the 70's and 80's. Its continued to become much more narrow and especially now looking at New York or even San Francisco so many galleries have closed, especially the galleries that once gave those chances to artists and really showed a variety of artists, they lost their space because of not being able to afford it and not selling as much artwork. There's a huge discrepancy now between art work that goes for hundreds of thousands and millions of dollars and then other artists who don't even sell work or it's for such a lower price and galleries can't sustain themselves. So I think now people are starting to have a reaction to that so they're doing a lot more pop up exhibits. I think artists are also trying to find ways to be more creative with getting their art work out there and making it more a part of society. That's one reason why I love the current exhibit I'm in, because it's not in an enclosed gallery space, it's outward, anybody can walk by and see it. I really do think more artists and people who are supportive of the arts are trying to do that. But it's definitely more challenging. We Bake Cakes and Nothing's the Matter - 2011 - oil on linen on panel Untitled - 2012 - oil on burlap on panel

JD: Do you have any words of advice or encouragement for other artists or young creatives who are struggling through the process, experiencing self doubt, stuck creatively, writers block, painters block, what kinds of things have people told you in the past or that you've told yourself that you would offer to other people? KA: I think the biggest thing for me when I have felt stuck with my paintings is to look to other creative outlets. I am hugely influenced by dance. For me, I feel as if having those different outlets, it always adds to my artwork and helps me to be creative even if I'm not the one creating the work. It gives your mind a different way to take in all this creative information. It's such a great learning ground. I read a lot, I watch a lot of dance or film, and music. I listen to a lot of classical music because there isn't a focus on the words, it's really just that emotional content. I think that's a huge thing to do, for young people, if they're struggling. And to reach out to other artists. Maybe you don't feel comfortable reaching out to students in your class but there's an artist you really love, send them an email, the worst thing that's going to happen is they're not going to email you back. But you might develop a really good mentor, even if it's online. If you're fortunate enough to get into higher education, and even if you're not, find your community of artists, even if their work is nothing like yours. For me, if I have an absolutely horrible teaching day or studio day, If I can go see a friend of mine in a creative industry it just helps me feel not as isolated. I think there's this idea of "oh, that's so great you're going to the studio, have fun," it's not really an adjective I'd use to describe my studio practice, and I don't mean that in a bad way, that's just really not the adjective I'd use. And I have so many non creative non art friends and then I can just talk about anything and get my mind off art. JD: A conversation can change so much. KA: Absolutely. Just putting in the effort to do those things, I think artists can get so tunnel focused and in the process get really isolated. I think trying to reach out of your environment is really, really important. JD: Do you have any new exhibits or upcoming projects you'd like to tell people about? KA: I have one up currently at NYU until September 6th. I have a solo exhibit in South Africa, in March. And then I have my first museum exhibit at the American University museum in Washington D.C. in June. All images © Kiley Ames (provided courtesy of the artist) For more visit www.kileyames.com/

Clare klein

8/27/2017 10:59:36 pm

I thought your comments about Kiley Ames' art were incredibly interesting, insightful and thought provoking. The art in her exhibition, In the Labyrinth, is amazing. Comments are closed.

|

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

April 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed