|

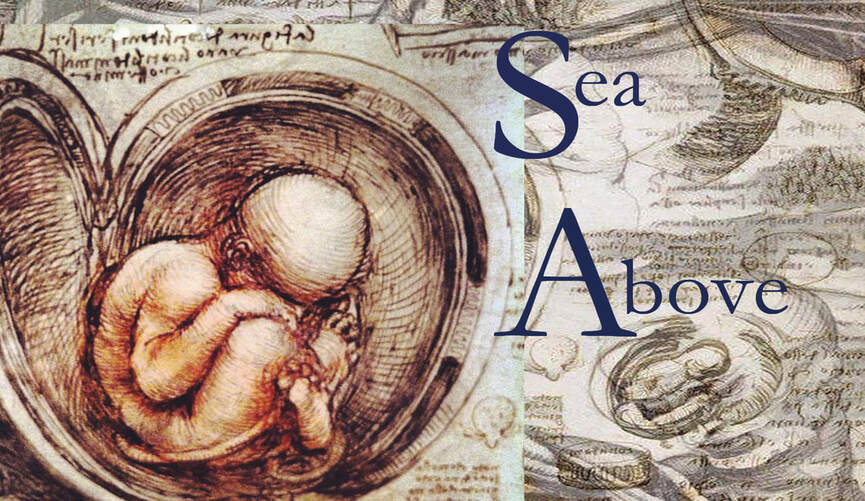

S’B’VE S’BL’W Alright, George Salis. Easiest for me to write this as letter to you rather than review or interview which I entirely intend it as mostly to shake the idea from me that I need to impress you, because that has decidedly come into my veins and I decidedly request it exit as its consistent cloud will lead most certainly to a shit response bent on a public face rather than something this scribbling can do, which is serve you a plate of what you’ve made mess of in someone else’s heart. To say: I read your book and liked it. I read it, excepting one night, on a series of ferries passing to and from mainland America. Our battered vehicle is in the shop and we’ve need of a rental to get to the hospital in Seattle. The longish voyage served perfectly: booth seating aboard with flat tables—easy access to get to a pen so I could thieve certain titles; yes: “a bare branch with a red hue”, “a crucible in a pipestem triangle”, “the flesh turned soil”, “the center of the tattered heart”—I’m sure you’ll see them on a stone wall somewhere with a string of my uncoiling done up underneath them. And if I don’t rip “all the furnace did was cover her skin in a thin layer of ash” verbatim from your grip, I’d be doing a disservice to whatever comes from my lineage. They’ll know I’m a crook because I’ll say I’m a crook, but I won’t have them saying I was a bad one. Yes. On the composite line, George, I tip my hat. Whoever suggested a cyclone came when you set the pen down had it right. My god what a spiral. As I wrote it in my notes: “The sense is somehow that it’s not the characters that are important but the symbols that Salis hangs on the hook: the stillbirth, the triangle, the sun-head angel, the upside-down cross, the flake, the molt, the flexible skin, the extended hand of God—these become my comfort as I read, rather than any familiar face or familiar home who and which are like as not to become queer, otherworldly, unreliable.” Because you shake shit up, don’t you? If a character comes in on a page, streaming through glass shards and in the gaps, pursue a God, they’re as likely to crawl into a stream as they are to radio in for help or find salvation. Options = infinite. That and we’re working backwards as often as we are forward, which—I feel like I’m doing that even now writing back to you, so let me just admit some quick linearity and start from my beginning. Adam. Parachutist. Adam with his palpitating heart. Adam. Sun. Atom. Son. The Coach’s kid. The deliverer of that fucking essay, my guy! C’mon! “On Falling Into a Vista”—seamless as hell; the interweaving of theological freight with speculative work with personal analogy with the slightest dapple of the story-so-far—very serious congratulations are due this chapter. I wager you know how good it is. “To Fly, Human, To Fall, Divine” I’ll stop and say: while yes Lars and Tabby’s return was a must, the weight put on this essay as Charles et al. become ref- and reverential to it gave me some recession: what was celebrated and singular became anointed by the crowds, and Jealous Me began to say: well fine, if everyone thinks its special, I’ll go find something else to faun over. Note. But Adam. Adam and his weak heart. Adam, like so many dads, who goes Nowhere. Adam whose buddy--best buddy for the book’s intention—is Charles, toilet-mouth Charles who learned how to spit fire in Motel Hell and presumably, in Iraq; Charles, who suffers from that other malady: the disappeared woman. Oy, where has Hellen gone? Oy, poor Tessa with her gills who despite herself just must be drowned, joining Peter’s poor Mari among the women who seem to merge as often with the infinite as remain in relation. Now Charles, Reggie, Jeremy—let’s say The Boys + Irene—have the conversational familiarity and kitschy indulgence of Tarantino: the chicken wings are in focus, the bongs are in focus, everyone’s saying poon like they’re comfortable with the word. I’m won and not—by the end I am—particularly with Charles who got the lovely supplements (his wife’s search the Charon poem, that brief beautiful moment with Adam saying something like ‘Yeah, dude. I’ll come help you look in a little bit.’) And, hands-up: I dig me a Slothrop sex scene as much as the next man (the black widow with Danny Boy in her web was inspired)—but the clubhouse-enter-stage-right-gib-gab left me a little hollow and a little worried. I think it was the dialogue. I think. I think it was because with a common feature of mutual ribbing and unsupervised bong rips, I lost track of why I needed to be there—a feeling way rare to the book as a whole—it sniffed of plastic Pynchon more than the more gorgeous you-stuff that leaked out elsewhere. “Piss up your ass if your guts were on fire” I think your power hit full force on p 73. “a longa time ago.” My critical self disappeared at first blush of a well-written robot-child whose autistic insides and abbreviated language was entirely earned and developed with me in stride with you. In a landscape of revelation, more revelation pales and the simple boy exists like the black pebble, unaware of his raw, unique utility. Young Isaac Newton. Young lamb of Abraham, sufferer in an endless string of lost fathers. Jesus, George: “He came to a row of bushes and jumped inside them—woosh!—like a shape shifter.” I don’t think you exited scene better. The story of Isaac is you at a subtler pace volume density: regular visits to the same locations; language growing and shifting from its inception (Austin’s rattiness, others); surprising turns by stock characters (Marco was definitely going to fail our Hero, I was sure) and if I’m again wickedly honest: that Isaac existed 100%-buoyed the two Adam-and-Evy-lay-in-bed-coo-and-cuddle moments for me, which, if they hadn’t said his name in a breathless whisper, would’ve remained dorm-room make-out scenes rich with teenage anxieties. Now the Adam & Evy orange scene? Very different story. You flourish in these moments of allowance, where the possibilities of the material world have secret compartments, where “marine beings...deep within the ocean…made of liquid pressure” exist. The weaving serpent-phallus, the orchard keeper, Isaac’s Pegasus coins—fantastic. Not subtle, but flavor with the quality of a good shrub: the color we expect with a startling twist. Now: thank you again for Jingle All the Way. On an entirely personal note, I need that to respond to the favorite Christmas movie question with something other than the Santa Clause, which blanched just this year to something inedible. I’d like to celebrate a few lines: “A black road in the distance turns a sliver of the world into a swaying curtain”, “a spine charged with the tension of an ill omen”, and perhaps the most gorgeous line from the whole book “Having lived a life of accumulated sin, as all men and pretending saints do, the sword of Damocles hung by a single horse hair above his skull, which was, aside from a civic crown of ashen bristle, naked in the most fragile way.” I mean. C’mon. Like I said: you hit or lulled me into your stride after Isaac. Lars & Tabby and their dad is a sequence I could read a thousand and one times. Those short tales of resurrection where stunning, “the rarely wise babbling of the nearly expired.”—gah@! I could go on with congratulations, George, but I’m going to pull up, summarize my thoughts, ask a few questions, and go have sex. You did good, man. It’s clear you’re going to keep doing so. You have nimble language control, you can be equally divine and profane, your world is filled with monsters and maidens. I’ll be curious to watch you do the quiet song of the grasshopper, as I figure you’ll keep aiming big while you have something to prove. I think it’s always worth a good recommendation: ‘the great Dilators’ that come up in your interviews are spellbinding and always remind me what is possible if we take to the page like your Father Peter: with “fists pulsing like a pair of hearts…reddened and tired of pounding.”—I will always be drawn there. Recently though, I’ve looked to Yukio Mishima’s Sailor Who Fell From Grace With the Sea for something else. Something I don’t know how to do yet. Perhaps you’ve been. I’d be curious if or when you have, what you think. Regardless: in the vein of your interviews which I read and applaud: Your character Mary is abused but believes herself in a better place than she was, or says so. “Sometimes it’s better to stay put. At least I have a better idea of what to expect.” Do you revile this statement? You’ve taught and lived away from your country of birth—what have your travels taught you and brought to your writing? I encourage travel, although I’m not so naive anymore to think it’s an antidote to close-mindedness and xenophobia. It can be, or it can reinforce the biases because the brain is often obdurate. Some people don’t necessarily have the money or means to travel, and it can indeed be frightening—just ask Samwise at the edge of the Shire—but one would hope that, at the very least, one would supplement any shortcomings by traveling through a bounty of books rather than a tetanus of television. Traveling has taught me about expansion and about connection, how humans are so diverse and unique yet still a single species: Homo sapiens. Myths mix and echo, and the same thing can be said about culture overall and genes underall (Adderall?). My travels to countries like Poland and my ancestral homeland of Greece are partly responsible for bringing those senses to my writing, if not scenes in particular. Which of the three things that happened to Hellen do you most believe happened? The novel is a form where multiple possibilities can coexist or disconcur eternally. In theory, the same is true of the mind but when it comes to navigating reality, I think certain possibilities must make like quantum mechanics and wave-collapse into the closest approximation of truth, without being absolutely certain in many instances. Rather than pick amongst the triptych, as it were, I think it’s more likely that Hellen died in the car crash. But when people go missing and closure isn’t there, ceaseless possibilities remain, and perhaps Schrodinger’s cat can be heard to purr, or not. Much of your work sets science and faith opposite each other—to make the cut requires surrendering the soul or setting it aside—where has this line of interrogation taken you? Are the pews sterile? Do the fluorescent halls of the hospital repel you as much as me? Or will you tell me something of balance? Science and faith are non-overlapping magisteria, the former changes with more knowledge while the latter is absolute knowledge in the absence of any reason except hope, emotion as the impetus. It can be traced to looking for meaning in life, surely, and I’ve found my meaning in the world of words and stories, in always interrogating and never being satisfied with a single Truth, and of course there’s the more obvious meaning I find via love for my wife and family and friends. I am interested in religions as myths and faith as a strange psychological phenomenon often if not always fueled by cognitive dissonance. So no, nothing of balance, but most readers have said that the interrogation in Sea Above, Sun Below is indeed balanced, which was a goal I had, to avoid as much as possible art as propaganda. The introduction to the novel was written by Chris Via who, aside from being a passionate and perspicacious critic, is of the Christian faith. Have you aptly considered fungus? I’ll search through my work-in-progress and you can tell me: “It was their fungal smoke that choked Me awake…” “…crawl and carouse among the twin titanic keratin trees with their fungus leaves and toenail fruit…” “Its eye opened in the manner of a fungal spore sac.” “…multiplied and flash-fried and ultra-sized and fungicide and amplified and yuletide too.” “…festooned from base to peak with a multitude of glowing fruits and fungi…” And if fungus is not enough for you, then you can “feed us fetus feet!” This is your first book, Sea Above, Sea Below, and it’s drawn the kind of heat that can boil a young writer’s blood. How do you dispense with concerns of ego, failure, daily? Being published by a small press after three years of rejection, I was expecting mostly silence, so I’m very grateful that many people have resonated with my novel. One reader read it by candlelight during a blackout in NY, another told me it kept him company in a psych ward, and here you are with this unexpected but warmly welcomed letter/review/interview. I also never expected to receive positive feedback from writers I highly admire, such as Alexander Theroux and Lee Siegel. Rather than inflating my ego, I think it grounds me in the sense of not having to grapple with insecurity, which can get in the way of art. Writing brings me joy and I’m putting all that back into the novel I’m working on now. Of course insecurity was at its peak when I was first stumbling in the dark, but now I strut in the dark, knowing that a niche of a niche of readers are looking forward to a maximalist work that is written in a tradition we mutually love. Another way of putting it is that a writer should really only compete with themselves, comparing their current output to their earlier work. When I interrogate the works of other writers, it’s not in the sense of competition, but in the sense of finding out what I love and why, what I didn’t love and why. Better to stand on the shoulders of giants, as it were, than act like a vain David. Which books deserve more readers? The ones that challenge, interrogate, innovate, abrogate absolutes. The ones in love with language and in hate with clichés. Those I write about in my column are only a handful in a desert sandful, awaiting the water of a reader’s ocular oasis, so to speak. However, if I had to choose one that has been most wrongly neglected in relation to how wonderful a work it is, I’d have to say Darconville’s Cat by Alexander Theroux, a masterpiece that fights against the apocalypse of wordlessness and celebrates a multitude of styles and forms. What would it take to undermine a mythos? A mythos undermines itself when it has so-called true believers. Conversely, a mythos mined can produce some kind of revelation that isn’t necessarily exclusive to the mythos. In terms of the novel as an artform, a mythos is undermined when it lacks some kind of polyphony and then becomes an Overmind, solipsistic if not soporific. Are you superstitious? I’m not superstitious but I am a little stitious. In all seriousness, the brain is an engine of superstition, an ostensible victim of pareidolia and a plethora of other illusions and delusions. I do my best to minimize the harmful and unproductive ones in my own life, the ones that are no longer useful outside a savannah or cave or medieval hut, etc. Look to Skinner’s skinny pigeons and Pavlov’s salivating dogs for portraits of dogma. Your book is punctuated by objects—they pop amidst the metaphorical turmoil of the character’s minds which often live in, or dip into the ‘pedagogic debris’ or ‘didactic pigsty’ that Adam’s father seems drowned in—characters literally feel at times as though they are coming apart at the particle level but the objects in their lives are so often objects of caricature—the Twinky, Danny the Fly’s goggles, the heart-shaped table, and the height-changing stool, for a few. What does material, the formed object, do in your world? What things do you treasure? I dearly appreciate your observations here and elsewhere. Going back to your question of superstition, I covet books in general and signed ones in particular. There’s an almost mystical feeling to a book that one knows was in the hands of its creator who branded it with their signature sine wave. This is materialism of a kind but my defense is, using an analogy, if the mind is what the brain does, then stories are what books do, allowing us to hear voices from decades and even centuries ago, a kind of technological magic. While a Black-Friday materialism is vapid if not self-destructive, I acknowledge too that we don’t have bodies, we are bodies, and should enjoy so-called earthly pleasures, food, drink, sex, low-brow entertainment, etc. I would not want to take residence in a Buddhist temple, for instance, where one is instructed to leave their shoes and minds at the door. Without minds, we are vegetables, minerals, inanimate. At the very least, it’s probably best to eschew the Happy Meal for a happy medium. Ideas have a lot of power, you say, sometimes more than the actual thing. What did Charles and Adam think about this when they thought about this? I said it or I wrote it? The distinction is often important, I think, especially if we’re talking about characters vastly different than me. And but so I think my purpose was to get readers to think about what they might think about, meaning Charles and Adam. If I took a minute to think about it myself, I think it relates to how ideas, beliefs, can act as powerful impetuses whether or not they’re based in what we might call reality. A somewhat random example, although not random because this has been something of a morbid obsession, is the tragedy of September 11th, Islamist hijackers who believe that what they’re doing is not only right, but will also result in a heavenly reward from the creator of the universe. And there’s also a hint of Magritte’s not-pipe in that phrase about ideas. Again, the omnipresence of television and smartphones, seeing and living in the world through screens which make the depiction of reality more real than reality. I’m now thinking of Huxley’s propaganda of the unreal, which chloroform-chokes Lady Liberty…. And lastly: the “secret to her survival…she treated her brain like a heart and her heart like a brain”--is this the express purview or secret recipe of the Woman? Or is it independent to the character? It’s definitely not a description nor prescription of Woman or Man or Human or Huwoman, rather Adam’s opinion about Evelyn, which she might or might not agree with. The only thing I trust my gut about is whether or not I’m hungry, and even then I’m liable to gluttonize. I trust my brain insomuch as I try to be aware of its faults and biases and tricks on myself, which is itself. I want to trust my heart to keep pumping blood, and although I was diagnosed with PVC like Adam, more recent tests have shown it to be so far benign and common. Yet the feeling of an absent pump, a pumping absence, will never register as entirely normal. No. Not last. Reginald says: ‘You think you know me, sweetheart” and admits something earth-shattering. Will you do the same? How many times must the earth be shattered? Once is probably too many. I’m more concerned with keeping the earth in one piece, not only so that it can remain habitable to humans, but even more so for the animals who aren’t as predatory and careless as we are. Will Morphological Echoes shatter the earth? No, but it will be a kind of bomb that can be detonated by maso-kiss-tic readers who want to experience its silent light and invisible sound, in-sin-eration. Perhaps an even more localized people-oriented bomb as invented and described near the end of Joseph McElroy’s Women and Men. The third novel, the sequentially-cinching ripple of the Echoes will take the form of more silent fortissimi with the working title that will work until it isn’t working anymore: Silence of the Sirens, borrowed purloined from the pearl loins of Kafka, whose particular spermatozoan story was deemed by this reader as aborted in utero, now being mentally yoyo’d back to a different fuller life by a different emptying writer, i.e. me, who wants to bring Ulysses full circle by emptying into the rectangular pages wyvern words for Greece, the spermatozoa multiplying into more flagellating pre-creatures even as I write its future predecessor, what I call Greek-isms, most of which will spawn stories within stories, characters within conundrums: Acropolis Eclipse, Icarus Eucharist, Anathema Anthem, The Menarche Monarch, Exodus of the Rexes, Metamorphosisyphus, etc. -ew Eric Westerlind writes stories, letters, poems, reviews, ordainments, essays, and the odd YouTube comment. He is the author of UGO. He lives with Alyssa, wherever. He works at Ewandi.com. George Salis is the author of the novel Sea Above, Sun Below, which was praised by Alexander Theroux and Rikki Ducornet. He's also the editor of The Collidescope, an online publication that celebrates innovative and neglected literature. His fiction is featured in The Dark, Black Dandy, Sci Phi Journal, Three Crows Magazine, and elsewhere. For about the past 5 years, he has been working on a maximalist novel titled Morphological Echoes. He has taught in Bulgaria, China, and Poland. Find him on Facebook, Goodreads, Twitter, and Instagram. Comments are closed.

|

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

April 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed