|

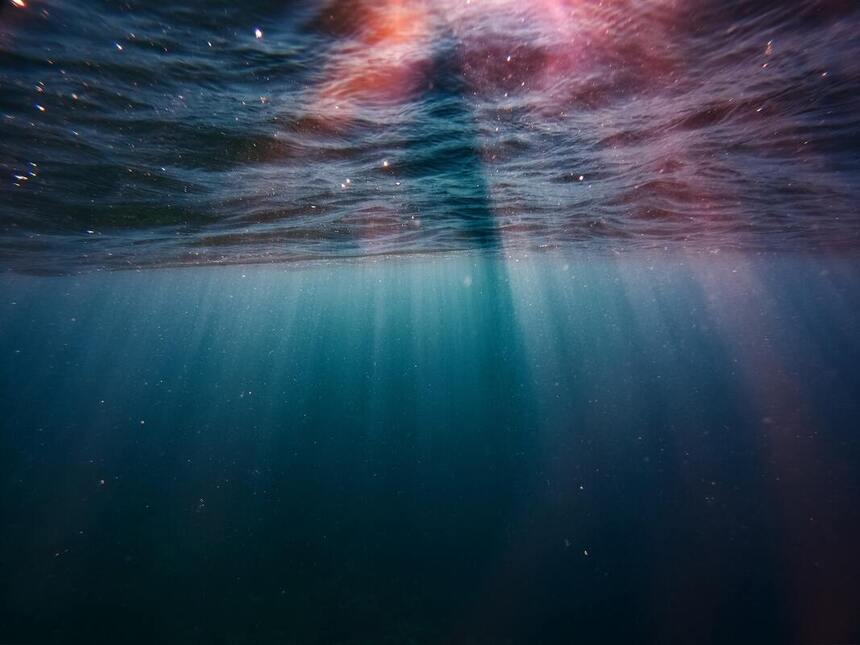

Screaming Underwater I saw a cardinal on the day of your funeral. A sky rippled pink like blood muddled bathwater. The cardinal flitted around a tree just beyond your gravesite. Were you there? Could you see me, hear me sobbing? My wife held me as I tried to stay standing. A car accident. The driver, your killer, too drunk to see he was in the wrong lane, well over the speed limit. Broad daylight. The priest spoke about your generous and beautiful life and everyone there was nodding, looking at the fresh hole, your new home. The gleam of the headstone, the cardinal resting on the marble. Sun shining in gradients through the high forestry around us, my mother silent and awestruck. My wife held me upright and I muffled my crying with a handkerchief and a clamped hand. Screaming helps. I spend day after day in your house, everyone coming in with casseroles and soups and vegetable platters. Everyone telling stories about you, about the good old days. Your friends stare at me uncomfortably and tell me how much I look like you. I nod and thank them, not sure what else to say. I can’t even look at myself in the mirror anymore, because of that. I inhale, and I scream. My wife holds me when it happens. The tears come so violent and loud. Tear ducts throb from overuse. Everything hurting. I scream into my pillow until flecks of blood end up on the pillowcase. Yesterday, I pulled a shopping bag over my head and screamed into the crumpled plastic. My wife came running into the room and poked a hole in the bag and tore it open, my hair wild and dewy with sweat. “I’m worried about you,” she says. I tell her there’s nothing to worry about but I think it might be a lie. Your killer got away with it. I follow him home from work. His lawn is a flawless expanse of green, the flowers an array of colors. Even the hedges look fake. The only punishment your killer got was a loss of license, so his wife drives. She parks her Audi in the driveway. His car sits mangled in the parking lot of an auto repair shop. He stares at his phone for several minutes before they leave the car and walk through the garage, the space taken up by golf and ski equipment, two kayaks hanging above a luxury convertible with a protective cover. He eats dinner with his wife and unwinds by watching television—the screen glowing on the wall like a framed massive landscape—and the wife’s phone keeps her face aglow until nearly midnight. She must not sleep well. She’s up early, walking around the kitchen downing mug after mug of French pressed coffee, her heels clacking against the expensive tiled floors. Your killer tightens his tie, some fruit and toast for breakfast, and they leave together. The therapist is my wife’s idea. The office is downtown, above a tailor’s shop, down a long hallway of peeling wallpaper. The office itself is drab, carpet faded from years of people fidgeting, sliding their feet as they uncover unfortunate truths, relive the past, cry in their hands recalling loved ones. I sit slumped in an uncomfortable chair. The therapist wears silky blouses with extravagant ascots and sometimes, even in the heat of the summer, she wears sweaters with bulky turtlenecks. She wants me to talk about you and what your death means to me. I give her the gist of it: the loss is too great, I don’t see how I can go on, my childhood was amazing and perfect and I couldn’t fathom how someone could love me so unconditionally and be taken from me without warning. I rage in the chair, I get up and pace around the room and whenever the therapist nods with her pen in the corner of her mouth I want to kick her hand and send the pen down her throat and watch her choke on it, fall to the ratty carpet and claw at her neck as she coughs up blood, fighting for air. She wants me to write a letter to your killer to get rid of some of these feelings. I want to do one better. My wife and I eat in silence these days. She comes home from work and slaves in the kitchen and I sit at the table and wait. Chicken, rice, vegetables. It’s all so bland. She eats slowly and daintily, and watches me as I poke at the food on the plate. “Do you want me to make something else?” she says. I shake my head. “I used the seasoning you like.” “There was a BBQ sauce my dad used to get that was really good.” “Do you want me to find it?” “We got it on vacation. I was young.” “Where was it?” “I don’t remember.” “Nantucket? Maine? Or was it that trip to South Carolina, when you were in sixth grade?” “Seventh.” I take a forkful. All I can taste is metal. “I’m going to have some wine.” “Okay.” I drink half a bottle of wine as the bathtub fills. The deep red of merlot—your favorite—makes me wonder how long I’d take to bleed out if I cut myself open and slid into the warmth of the bath. “May I join you?” my wife says in the doorway. She’s untying her robe. “No,” I say. I take a long pull from the wine. She looks hurt. “I’m sorry, just… not tonight.” She tightens the belt on her robe and from down the hall I hear her say, “Okay.” My boss calls me into his office. The metallic taste in my mouth comes and goes. My throat is sore from screaming in my car on my lunchbreak. “You sleeping at all?” he says. He already knows the answer to the question. “How are you doing, really?” “My dad’s office was about this same size.” He nods. “He had a recliner in the corner of his, though,” I say, pointing at where my boss has his copier and fax machine. “He worked a lot, so he liked to take naps sometimes.” My boss waits, lowers his voice. “You were late again today.” “He had the same faux-wood paneling on the walls, too.” I rub at my neck. Talking hurts. “If you need to take more time,” he says, “please do.” “I’m okay.” “You don’t seem okay.” I want to scream. Will I ever be good enough? Am I doing the right thing? Will my life turn out okay? Are you proud of me? “Did you hear me?” my boss says. “Yes. Sorry.” He shakes his head. I sit in my car and scream into my elbow, the scratchy polyester of my uniform absorbing the sound and spittle. My wife holds me. My entire body is shaking, and I’m trying to keep it together. Everything hurts. She’s shushing me and running her hand on my head and cooing and telling me it will be okay and I’m screaming. “I’m not okay.” She tells me I am. “It hurts.” She says she knows. “I miss him so much.” She’s crying, too, and I’m trying to stop myself from hurting her. I only want to hurt myself. An entire bottle of pink champagne for dinner, and all I can see in my mind is pink bathwater pouring over the sides of the tub and staining the white tiled floor. Would she pull me from the water and try to save me? Does she know what the pain in my head feels like? Can I ever soothe the ache that spreads like a cancer throughout my body? My arms and legs heavy, my lungs hollowed out from shrieking. Nothing else to do with what I’m feeling. More wine, vodka, old pills in the medicine cabinet. The questions circling a track in my mind, everything I needed to ask you echoing until I try to drown it all out. I’m just so tired. There’s a cardinal by your grave again. I’m sitting in the grass, the ground littered with acorns. Squirrels scamper around between the headstones. The gigantic old elm trees—planted in the early days of the cemetery, late 1700s—keep the older headstones in perpetual shade. Moss over the marble like a disease. The area where you’re buried is more open to sunlight, the gravesites littered with new flowers and keepsakes. Everyone around you lived longer. Seventy-nine, eighty-two, ninety-four. What gives them the right? Why do they get to live longer? Why do their families get to spend fifteen, twenty, thirty more years with their loved ones? Why have I been cursed to lose you so early? Strangers older than you don’t deserve the air in their lungs or the blood in their veins. That’s what I’ve started to do—stare at old people, watch them walk. If they struggle, I want to sweep their legs out from under them and wring their necks. I want to beat them to death with their own canes, feel their brittle bones snap and crack beneath their paper flesh. Why? Why should they still get to be here? Why should they retire and spend their years with their grandchildren, passing down wisdom and sharing laughter at holiday meals and on seaside vacations? What makes them special? The therapist says I need to think about all the positives from your life. All the lessons you did get a chance to teach me. How to be a good man. How to love a woman and a family. How to use my hands, sod a lawn, build a chair, dress a deer. How to light up a room with a smile, keep everyone at a party occupied with humorous stories. How to save money for a rainy day, what to do when that rainy day comes. Adaptability. How to keep that smile on your face no matter what life throws at you. That’s the lesson I’m going over, and over and over. It’s not helping. “The therapist says I should write a letter,” I say one night. My wife nods. She’s eating, but I’m not. Vodka still burning in my stomach from the ride home from work. “Well, a couple of letters.” The scratchy fork against the plate. “I should write a letter to my dad. Just about how I’m feeling, and all the things I think about him.” She nods. “And another to his killer, just like, letting him know how disappointed I am. How much he’s let me and my mom down.” “And me,” she says. “And you. Of course. You lost him, too.” “Write a letter to me, I mean.” I drain my glass of wine. “Right. Yeah, I could do that, too.” I grab the scotch off the top of the refrigerator. My boss calls me into his office again. The copier and fax machine have moved. He’s placed two filing cabinets in the corner of the room. The paneling is gone, he’s repainted the walls. Everything brighter, almost sterile. Even the chair feels different. Stiffer. “You were three hours late today,” he says. “I don’t think I like the new paint in here,” I say. Give a little chuckle. “I can’t keep doing this.” “You know, those filing cabinets should just go into a closet or something. You’d probably love a recliner in here.” “You’re done. I can’t have you here anymore.” “What?” I lean forward in the chair. My ears feel like they’re packed with gauze. “Get your shit. You’re fired.” The therapist thinks I need to reel in my anger. I pace in her office and during our sessions I occasionally glance out the window at the people walking around downtown and I hate them all. I think about how the office would be a perfect vantage point to take them out. Everyone an open target, wasting their lives, not deserving of being here. You’re not here, why should they be? I want to throw the therapist through the large window in the center of the room and let the glass shred her skin, have her bleed out on the pale concrete below as a crowd gathers. I’d go down to join them and wonder why did she do it? Why did she jump? And being that close to them, I’d pull out the dull letter opener from her desk and swiftly stab them in the lower back, the thigh, saw at their femoral arteries and leave a trail of bodies fumbling and chaotic in puddles of black and maroon, sirens wailing, the whole town in shock and wondering why this, why them, why now? What have they done to deserve this? What have I done to deserve this? “What have I done to deserve this?” I say to the therapist. I find myself on the floor, curled up in front of her chair. She’s reaching down to help me up and I feel it happen: I swat at her, scream, stand up quickly—the blood rushes to my head and I get dizzy—and I grab her by the woolen lapels of her jacket and shake and shake, her glasses jostle off her nose. She’s trying to speak but she’s stuttering, locked into a fit of terror. I grit my teeth, over and over I shout “What have I done to deserve this?” and she’s calling for the assistant and soon the assistant’s in the room and pushing me, prying me off the therapist, and with my fists still clenched I leave the room, the office, crashing against the walls of the narrow hallway, shrinking vision, my cheeks stained and pulsing from tears. In my car, I bite the seatbelt and scream. There’s a U-Haul in the driveway. My wife stands on the front steps of the house with her face in her hands. There’s a bottle of whisky somewhere, maybe the garage. I find it and take a long pull as she leaves the driveway, the trailer knocking around over the bumps in the street. The sunset a furious wildfire against the horizon. The man that killed you is working late tonight, all the other offices have gone dark. I sit in the far corner of the parking lot and wait for him to come out of the building. His wife will not be picking him up tonight. He emerges from the building with his jacket tossed over his arm and his necktie loosened. He looks around the quiet parking lot, craning his neck for a sight of the Audi. He makes a phone call. There’s no answer. I drive out from the shadows and ask if everything is okay. “Who are you?” “I work on the third floor,” I say. He eyes me warily. “I’ve never seen you before.” I shrug. “I’m new.” “My wife is coming.” I look around. The tree limbs sashaying in the dim light. My heart knocking wildly against my ribcage. “She’s not coming,” I say. “What?” he says, trying to hear my whispers. I want to hop out of the car and tackle him and throw him in the trunk but I have to stick to the plan. “I can give you a ride if you need one.” He frowns at his phone. He considers all his options and reluctantly says, “Okay.” Statuesque in the front seat, his arms folded. With him in the car, I finally notice the stale air around me. I hope he doesn’t see the vodka bottles on the floor in the backseat. I want to tell him I’m not like him, that I don’t drink enough when I drive to ruin lives like he does. He fidgets slightly, spending most of the ride stiff and stoic. Discerning me with unease. “Are you in the attorney’s office on the third floor?” I fumble at the air controls and the music. “Uh, yeah, I’m an assistant there.” He tenses up in the seat. “Who are you really?” I speed up, take a sharp left turn. “I didn’t tell you to turn here. How do you know where I live?” I pick up speed towards his house, come to a bucking stop in the driveway. He grabs his jacket and briefcase and scrambles to get out of the car but I’m faster than he is, the old piece of shit, and I grab him and usher him into the house and as he’s calling out for help I wrap my arm around his head and plant the handkerchief on his mouth and feel him squirm, flailing his arms, trying to hit me in the head with his briefcase. His footing is awkward, unwieldy, his dress shoes stomping and skittering across the expensive polished floors. He’s still calling for help, his cries growing more feminine and childlike, echoing off the high ceilings and the bulky leather furniture. “No one can help you,” I say. The wife. She lies writhing on the cold basement concrete, her mouth duct-taped, hands and feet zip-tied, the plastic restraints ringed with blood from struggling. “Please, please don’t hurt her,” he says. Her face contorted and daubed with tears. Muffled cries. “Are you upset?” I say to the wife. I tighten my grip on the husband’s tie, a sharp inhale of fear and pain. “I’m upset. Your husband killed my father.” She understands. Her body shrinks in acknowledgement. He’s sobbing and asking me to stop as the zip-ties cling to his aging flesh. His last cry is stifled by the duct-tape wrapped violently around his head. A chair meant for viewing children’s soccer games becomes my throne and I observe the couple. The wife, shaking, a stain on her pants, her eyes pleading up at me. The man’s face in perpetual fury. In the dark of the basement I scream, staring at the couple as my vocal chords char. They recoil at the sound. It takes me over an hour to drag the man that killed you up the two flights of stairs. On the way up, I pepper him with photos of his family, his children grown and out in the world with kids of their own. The photos in their heavy frames bounce of his body. Why does he get to have more cherished moments with his family? It makes me sick, thinking of the frames lining the hallways, the knowledge that there will be more to come. I pull him by what’s left of his brittle hair, kick him into the master bedroom, drag him towards the bathtub. I keep the water as hot as I can, almost scalding, and I thrust his face down again and again, a few seconds at a time, his muted screams and my hands burning. The drowning attempts are exhausting for both of us, chests heaving, arms tense and strained into overuse. We sit in silence for what seems like hours. I slowly peel the duct-tape away. “I’m sorry about your father,” he says. “I didn’t mean it, I wasn’t thinking, if—” I shake my head. I’d like to kill him. I’d like nothing more than to hold his head down under the water, his hair oozing out like a jellyfish, bubbles produced by shouting, the thrashing struggle until his lungs fill up and his heart stops. The unfortunate task of finishing off his wife as well, trudging down into the basement to slit her throat like livestock and just leaving her there. But it would be useless. You would never want me to do this. You wouldn’t be proud of me anymore. That’s all I ever wanted, you know. I just wanted to hear you say it one more time. I just wanted one more conversation, just to ask all the things I’m left wondering. What am I here for, what am I going to do with my life, without you around? Do you love me? Will this pain ever go away, will it ever make sense? How do I know if I’m doing the right thing? Am I a good man, are you proud of me? I cut loose your killer’s restraints. I tell him to go tend to his wife, set her free. I tell him to call the police, that I’ll wait here until they arrive. He rushes out, his cries a mixture of fear and relief. I hear his feet slamming down the stairs. Calling out for his wife. I hold my head over the water. The heat still rising, the steam curling off the surface. I plunge my face into the warmth, eyes open, and I scream.  Christian Gilman Whitney is a former high school English teacher. He was born and raised in Western Massachusetts, and earned his MFA in Creative Writing from Bennington College. He has been published in Gulf Stream Literary Magazine.

Marissa

11/9/2019 12:08:42 pm

I really enjoyed reading this & feeling the sadness, anger, and heartache of unexpected death. I was able to visualize so much of this story. My eyes are wet.

Cord

11/11/2019 03:39:35 pm

Excellent read. Terrifying, engrossing, and haunting. Well done.

Steve Corbitt

1/5/2020 08:20:58 am

Christian - This is amazing writing. The emotion incredible. You truly have a gift. A much larger audience deserves to read your work. Get it out there. Comments are closed.

|

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

April 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed